When we were studying, we did not have any idea that we would choose a profession later. Our parents only wanted us to graduate and get married. They would not have thought of sending us for a job.

– Lucy Varghese, High School student in the 1940s, Kozhikode, 2023

Women’s educational access played an important part in raising the literacy levels in Kerala. Malayali women’s voices—interviews, autobiographies, and biographies on their educational experiences—narrate the past and the events that influenced their own and other people’s access to education. Some of these journeys were difficult, some were easy, but they were all different.

Sidra Ali - From Jeddah to Kerala

“All schools in Saudi only work till 1:45 or 2:00 PM. There’s a rule that boys’ and girls’ schools should be separate. From the third standard onwards, boys and girls would be in separate schools. We had separate buildings for boys and girls in our school in Jeddah. Our bus service started at 7:15 and went on till 1:45. The boys’ section would start at 9:30 and end at 3:00. So, my brother went to school at a different time.”

– Sidra Ali, 2024

A friendly throw ball match between senior students and teachers, girl’s section of the International Indian School Jeddah, 2016-17. Image: Sidra Ali, 2024

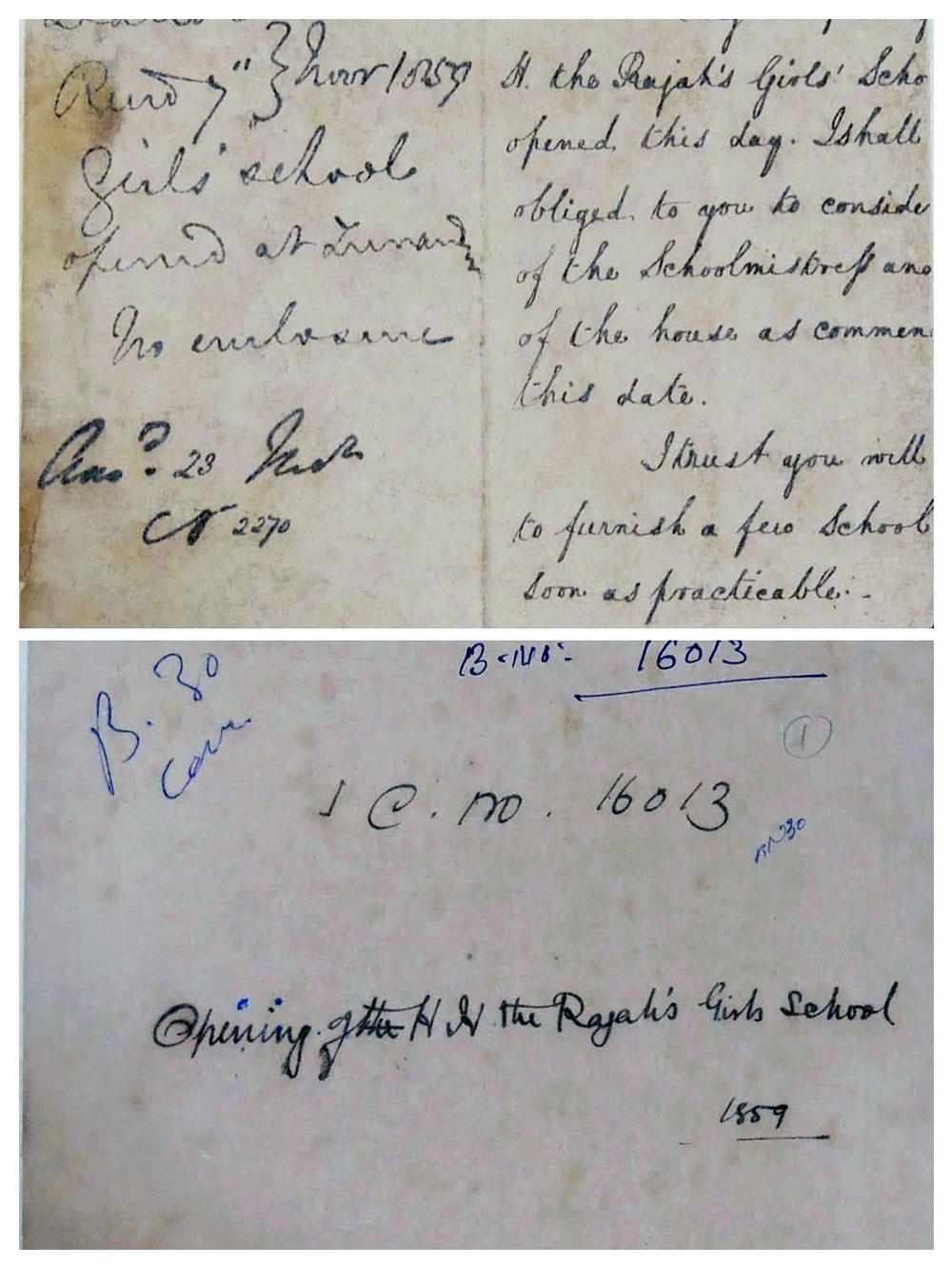

Advertisement of TISS from the Gulf Madhyamam weekly supplement, Chips, 2012-14. Image: Sidra Ali, 2024

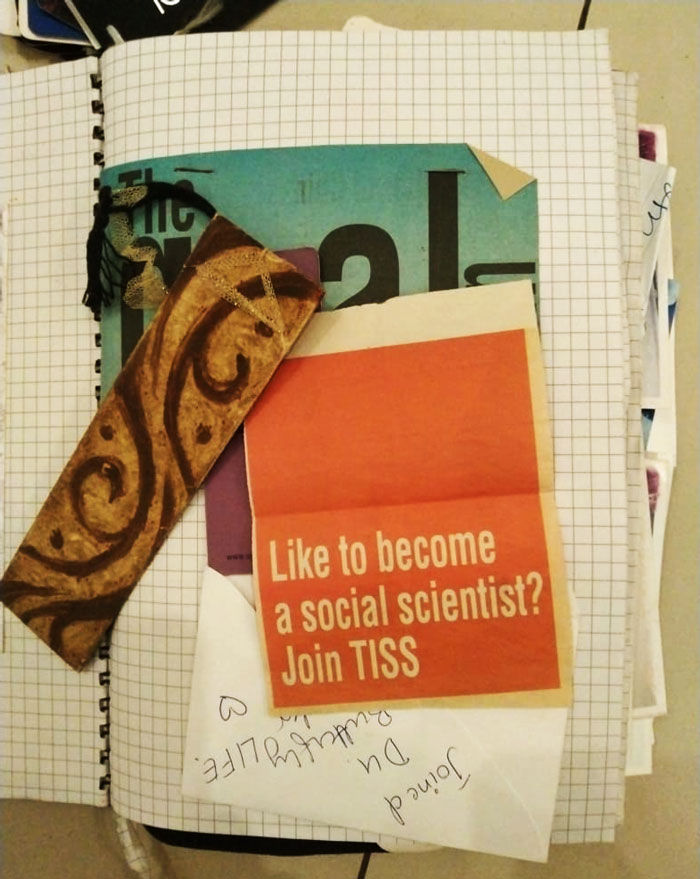

“The humanities teachers did not have anywhere to guide the students because they were sure that the humanities stream wouldn’t make enough money… Most of our family friends would be Malayali science teachers or the people we would meet outside the school would be Malayali teachers. Their students were guided onto science streams based on their marks; everyone else is moved to the humanities and arts stream.

There was this article in Manorama that said, ‘Do you want to be a social butterfly? Then join TISS.’ Somebody who had studied at TISS wrote this. I was like, what a wonderful word. The article said you could become a social scientist. I took a cut out of the article and pasted it in my journal.”

– Sidra Ali, 2024

“In Malappuram, and Malabar in general, women are more formally educated than men. Men usually try to settle down earlier. Women continue their studies even after marriage. These aspects are discussed beforehand. The educated women in my generation and the older generation, a majority of the women from my mother’s generation, are working—there are teachers, doctors, engineers, and those in government service. The husbands usually engage in business or are based in the Gulf.”

– Sidra Ali, 2024

Sidra Ali, extreme left, with friends at high school graduation. International Indian School, Jeddah, 2017. Image: Sidra Ali, 2024

Mary V.D. - Interrupted Education

Mary V.D. 64-year-old household maid in Idukki, has worked on the grounds of the local landlord’s family traditionally. She was sent to an asan kalari (single-teacher school where the alphabet and basic numeracy are taught) to learn writing. Everyone in the locality was sent to this asan. She remembered sitting down cross-legged and writing in the sand in front of her. They used a palm leaf to write the Malayalam alphabet

“I studied in two schools—in the local government L.P. school till fourth and then one year in fifth at the English school, St. Sebastian’s School. All the people in the locality studied in these two schools then, since the government school only had up to Standard 4. We did not have any bags. We carried the books in our hands. I found English and mathematics difficult. Malayalam wasn’t so bad.

We were given upma at school. I used to come here (the house of her landlord) during lunch and have kanji daily. Nobody remembers that now. I used to not eat the upma.”

– Mary V.D., 2024

Mary V.D.

“My sister and one of my brothers went on to college. I was the oldest. I entered work as a housemaid because money was needed at home… I wasn’t really sad about stopping school… I don’t think schooling has particularly helped me. Of course, I did learn to read; that was useful. Most of the people in my locality who went to school are working in Kudumbasree now.”

– Mary V.D., 2024

In conversation with Mercy Alexander, Kerala Museum, Ernakulam. Image: JANAL Archives, 2024

Mercy Alexander – Education and Community

Mercy Alexander was born in Mariyanad, Thiruvananthapuram in the early 1950s.

“Children used to refuse to sit with us, saying we were smelly. We had two sets of uniforms, one of which had to be kept at school. In case it rained and our dress got wet, we were supposed to change into the one kept at school. I did not often have this spare and was made to stand outside as punishment by the nuns. School life was really difficult.”

– Mercy Alexander, 2024

“Together with other social workers from India, Italian missionaries started a six-month residential training programme for girls who had not passed the 10th Standard exam. After training, these young women could go back to their villages and start women’s samajams, nursery schools, credit unions, and health-related activities… An older girl from my village had gone there, returned, and started a nursery school. She asked me to join the training since I had not passed my 10th. She said, ‘You have an affinity for social work and a talent to speak. Why don’t you join this training programme?’ I was interested.”

– Mercy Alexander, 2024

Fisherwomen at Valliyathura, a village near Mariyanadu. Image: Soteyn.pro, 2024

“I am the third girl in the family. When my mother went back to her house with me, they asked her, ‘Do you have any financial savings here to come back after having given birth to a girl?’ I grew up listening to this. Hence, I decided from childhood that I would create an atmosphere in my community where a girl child is not considered a burden and dowry is not a hurdle. I grew as a feminist, environmentalist, and social worker, and gained the ability to raise my voice against inequality.”

– Mercy Alexander, 2024

Lucy Varghese - Extra-curricular Education

Lucy Varghese, 88-year-old with a Diploma in Physical Education from Chennai, chose an educational trajectory that was not typical. She was the first Keralite woman to win a medal in athletics in the National Games.

She stayed with her parents and completed high school at St. Joseph’s Girls High School, Changanassery. At St. Joseph’s, she realised that she had an aptitude for sports when she came much ahead of the other competitors in a running race.

“It is in Changanassery that I started my sports career. I used to go to competitions, and I used to get prizes also.”

“In the first year itself, I became the inter-collegiate champion at Women’s College, Thiruvananthapuram. There was no looking back for me. When they started hockey, I was on the team.”

– Lucy Varghese, 2023

“Usually, women from our families—of our standing in society—did not allow girls to participate in sports. But my parents were broad-minded. They did not have any issues with me participating in sports.”

– Lucy Varghese, 2023

One of her teachers directed her to the Y.M.C.A. College of Physical Education since she thought Lucy would do well in a physical education course as she had an affinity for sports and was part of the hockey team. She said of her sports career in Kerala, “There were many people to encourage us. It was nice.”

Lucy was the state president of the women’s hockey team for several years. Lucy retired as Principal of the Physical Education College in Kozhikode, where she worked for 10 years.

Uma Chandrakumar - A Woman's place

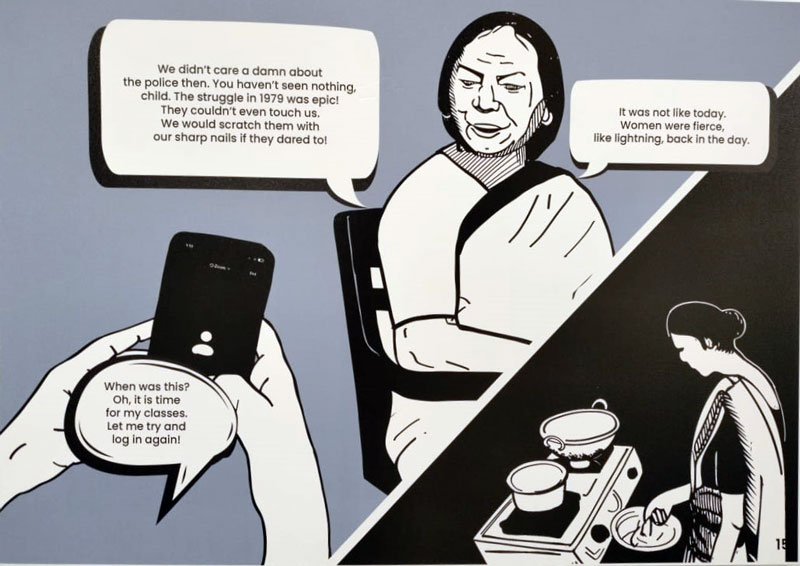

“The first thing that the teachers used to check at the school on Mondays was the length of the students’ nails.”

– Uma Chandrakumar, 2023

Uma Chandrakumar, studied at Baker Memorial Girls High School, Kottayam, in the 1940s. Being the daughter of a lawyer belonging to a Nair household, access to school was relatively easy.

Discipline and deportment were important in the school. In the past, health and physical exercise were given equal importance in all missionary schools. Needle work or Music were optional subjects that students had to take exams in for their SSLC. In Baker Memorial school, there was baseball and athletics. They used to have inter-school competitions.

Uma Chandrakumar in NCC uniform from the mid-1950s. Image: Arun Kumar, 2023

Uma Chandrakumar studied at Baker Memorial School in the early 1950s. Image: Arun Kumar, 2023

“I wanted to teach. That was the best job for a woman.”

– Uma Chandrakumar, 2023

Uma joined the Women’s College in Thiruvananthapuram to do a BA in chemistry. Though she had wanted to do medicine, her father said it would take a long time to complete the course. Consequently, her marriage would be delayed. Since she had younger sisters, he could not wait for her to finish her education, as their marriages would also be delayed. She taught English for a short while at a nearby school after her graduation.

Devaki Nilayangodu - Home Schooled

Devaki Nilayangodu (1928-2023) mentions in her autobiography Kalappakarchakal (2008) that girls were not allowed to join school, rather, tutors were engaged to teach them at home.

“A Nair woman called Thankam from Guruvayoor was brought to stay at the illam. She had passed tenth. The teacher taught me mainly English. And a little bit of history and geography. I did not like mathematics; so, the teacher did not teach that.

Thankam teacher taught me for six months. I attained enough proficiency to read the Standard 8 textbook. I could read boards and write my address. I could read certain English novels after my marriage with this knowledge of English, like Pearl S. Buck’s Good Earth, Stories of Tagore, Pride and Prejudice, and so on.”

– Devaki Nilayangodu, 2008

Women were not allowed to study Sanskrit in their community, but her sister was so adamant that their father relented. By then, her sister had had her menarche. This posed a problem because women who had reached menarche were not supposed to see (male) strangers. Their father found a solution. The teacher and student were made to sit in adjacent rooms, and he sat in the doorway of the two rooms. The guru would say the shlokas aloud. Nilayangodu’s sister would repeat it aloud from the other room.

Once their father became busy and could not find time to sit in between the rooms, her sister’s education came to an end.

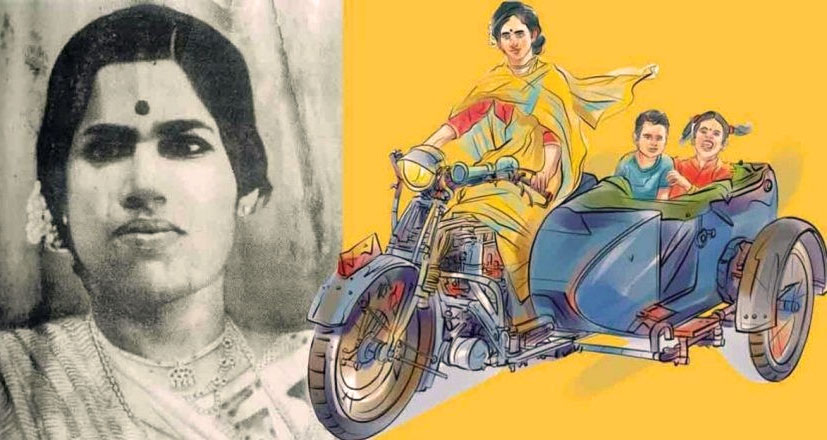

Gouri Amma was the first Ezhava woman to pass the Bachelor of Law in Travancore. Image: Aatmakatha, 2010

K.R. Gouri Amma - Education as Liberation

K.R. Gouri Amma (1919-2021), lawyer, former revenue minister, and noted Communist Party member was born in a fairly rich Ezhava family. Initially, she was sent to a local school run by a single teacher.

“The children were taught to write, speak with clarity, read according to their ability, read and understand poetry by Kumaran Asan, learn certain poems by Kunjan Nambiar and Ezhuthachan, taught arithmetic, addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division according to the child’s ability…

It was only students from rich and propertied families among the Ezhavas that went for English education in those times. There were no fees for lower castes and Dalit students. Even then, very few went to school. None of my uncles’ children had a college education. Students from Dalit communities studying in English schools were about five per cent, less than their numbers in the total population.”

– K.R. Gouri Amma, 2010

When Gouri Amma joined the high school in Cherthala, Alappuzha, she found that the students were from a different social background than the one she was used to.

“Around half the students at Cherthala High School were the children of government officers, businessmen, and landlords. Their behaviour and dressing styles were different. As a result, the atmosphere and discipline in this school were also different. It was compulsory to wear clean clothes, to plait or brush one’s hair, and to learn one’s daily lessons.”

– K.R. Gouri Amma, 2010

The T.D.H.S. where K.R. Gouri Amma did her schooling. Image: instagram/td_school_thuravoor, 2024

Education did not always mean the academic kind during that period. Her elder sisters, were trained in vocal music, fiddle, veena, and harmonium. Gouri Amma remembers acquaintances coming to the house to listen to her elder sister K.R. Narayani Amma’s musical performances.

K.R. Narayani Amma, adept at riding a motorcycle with a sidecar, would often take her child and Gouri Amma (7–8 years of age) on rides into town in the 1930s. In an era where cars, buses, and even bicycles were rare, crowds would gather to watch her ride, cheering and whistling, much to her sister’s annoyance. Despite the attention, her sister persisted until their father intervened, citing that the time was not right.

B. Kalyani Amma - Mission Schooling

B. Kalyani Amma (1884–1959) enrolled in school around the turn of the century. Due to her family’s financial constraints, there was doubt as to whether she could continue her high school education. But with the assistance of the Zenana Mission School administration, books, stationery, a monthly stipend, and a private tutor were secured for Kalyani Amma and her peers. She completed her education as a private student of the school, as the institution did not formally have a high school section. This initiative underscored the school’s commitment to providing educational opportunities for its students, reflecting their dedication and interest.

The building of the school, an old palace, was reputed to be haunted by a ghost. The top floor of the building was made entirely of wood, including the floor and walls.

Kalyani Amma mentions, in her autobiography, that the study of science and scientific principles changed her thinking. The eerie bumps and knocks were caused by the seasonal shrinking and expansion of the wooden boards, she realised. Despite her and her friend’s efforts, they were not able to persuade other students and teachers that the ghost did not exist. Not everybody was ready to give up traditional beliefs when confronted with the rationality inherent in modern education and science, she writes.