Mechanised Fishing, Part 1: The Indo-Norwegian Project

Traditional Fishing

Travancore state made sporadic attempts to develop the fishing industry in the early twentieth century as part of its reformation policies. The government provided wood for boat construction, cotton yarn for fishing nets and a refrigeration plant in 1938.

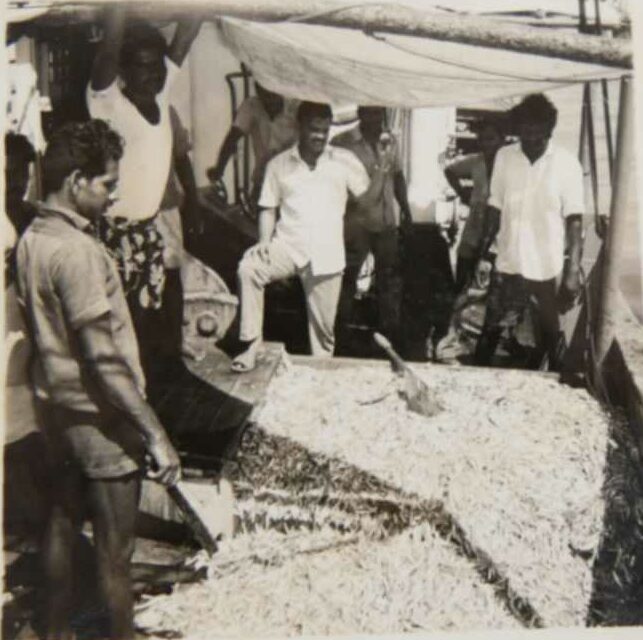

With the existing craft, fisherfolk caught fish up to 5-6 miles from the shore since their catch would be spoiled before they reach the shore if they were out longer. Consequently, by 1951-52, fisherfolk customarily caught fish for daily needs, dried what was left over and threw away the rest. There were no functioning ice factories, and salting was the only means of saving the surplus catch, but it was not popular among the local population.

The Grow More Food Campaign

The Second World War and British mismanagement led to a severe food shortage in the 1940s and consequent famines. A Grow More Food Programme was initiated to address this, which gained momentum after Independence. As part of this, a fisheries sub-committee was formed to organise fishing activities and adopt modern fishing techniques and the latest technologies from fishing industries in Scandinavia.

The 1950s was an era in which India developed technical ability in various fields, from steel plants to IITs, with international assistance. The Indo-Norwegian Project (INP) was part of the UN Technical Assistance Programme for post-war reconstruction and assistance aid to newly independent developing countries.

The Norwegian government sought countries to share fishing technology with and contributed to the project’s capital, equipment, and personnel. In contrast, the state and central governments paid for local expenditures. The INP project began with a tripartite agreement between the UN, Norway, and India in January 1953.

“The beginnings of the INP were in the second Five Year Project of India. After agriculture and milk production, the government of India turned towards the fishing sector.”

…Varghese John, Marketing Officer, NIFPHATT

The Indo-Norwegian Project (INP)

In total, five supplementary agreements were made with Norway during the project. A supplementary agreement was made in 1953 specifically for developing fishing communities in Travancore-Cochin. The project started in Kerala because the state had fisherfolk villages and a long shoreline. This project had four main goals: (a) To help fishermen earn more. (b) To make sure fresh fish was distributed efficiently and improve fish products. (c) To better the health and sanitary conditions of people in the fishing communities. (d) To raise the overall quality of life in the project area.

INP at Kollam

The INP began in Neendakara, Sakthikulangara, and Puthenthura in Kollam. Two fishing communities on both sides of the Neendakara Project area were chosen, which covered about 25 square kilometres. These communities had a population of around 12,000 and approximately 400 fishing vessels. The villagers were poor but intelligent and fit the criteria of needing socio-economic development.

“The Indo-Norwegian project was about socio-economic development… It did not feel like an office, but a collective of people dedicated to providing value to fisherfolk’s lives.”… K. Ravinath, former deputy director, NIFPHATT

The INP started a Primo Pipes pipe factory to distribute potable water and laid pipelines. Sanitary conditions in the villages were inspected, and around 1,200 latrines were constructed.

Doctors and health practitioners were brought in from Norway, and a health centre was established in Kollam. Children and pregnant women were counselled, and trained midwives and nurses were sent on home visits. Medicines, milk powder, and vitamins were given away for free.

A staff at the hospital mentioned, “The hospital ran well when the Norwegians were here. There were specialists for children and women. Training and treatment were also given for other diseases.”

Development of Boats and Fishing Techniques at INP

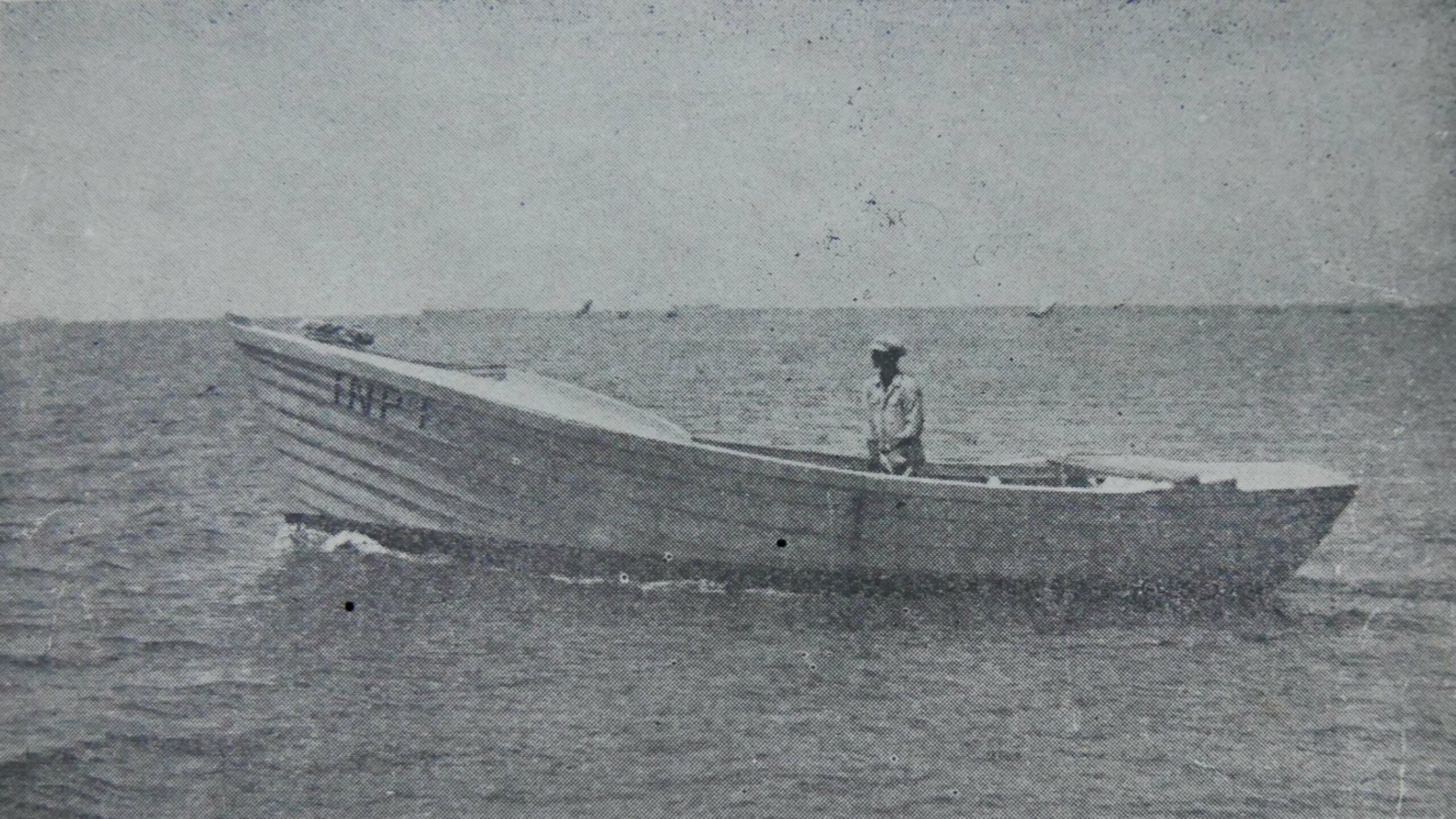

The Indo-Norwegian Project transformed traditional boats (valloms) by mounting motors. Later, motorboats were constructed. Fishermen were given training for six months, and more than 60 boats were built, taking into account the breakers at the Kollam beach.

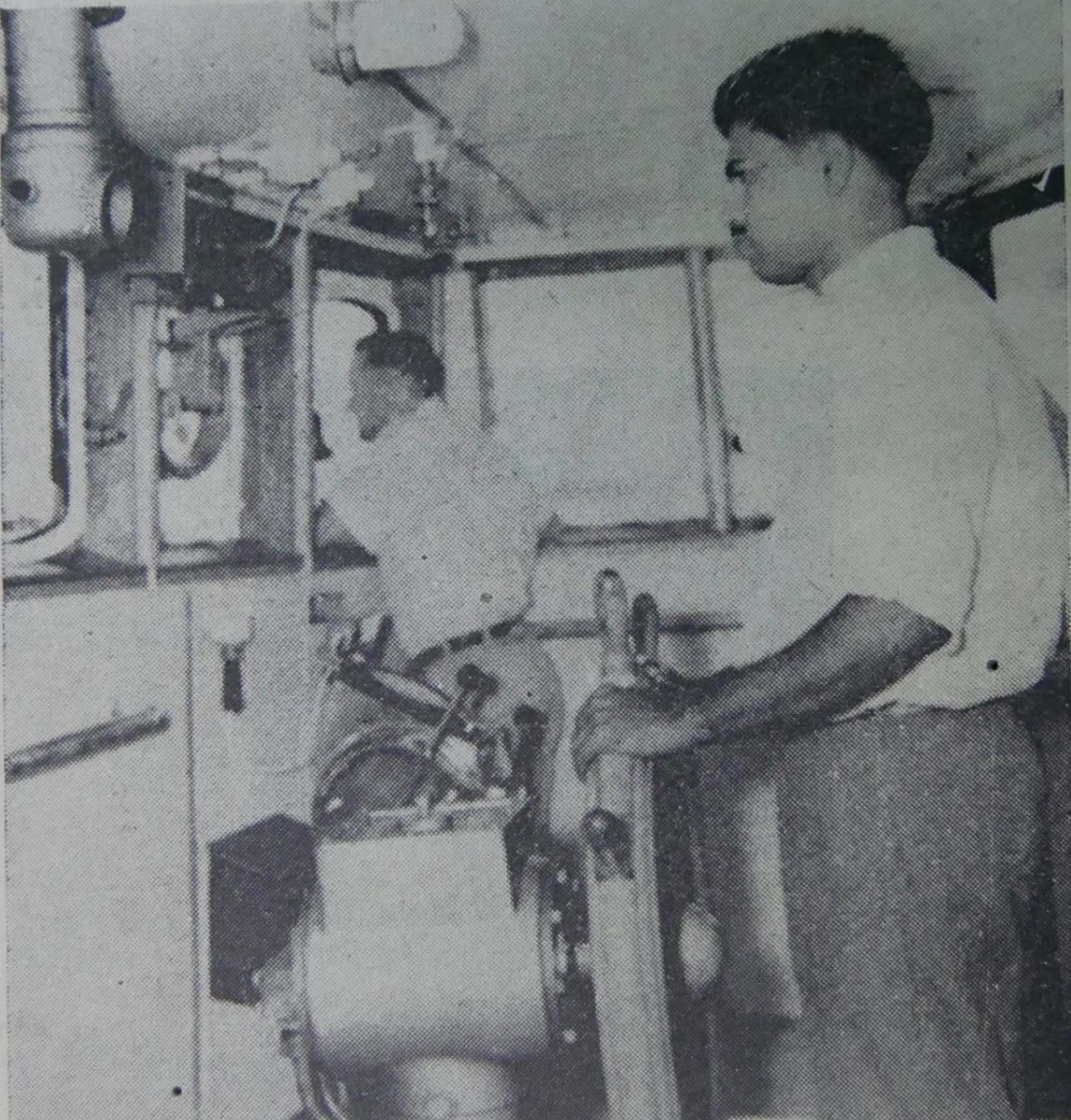

Mechanised boats were built shortly with engines fitted inside the boat’s hull. These new boats had to be operated from small harbours or estuaries. Concurrently, fishing methods were developed, including the use of trawl nets. The trawling boats were different from the canoes used until then. There was a cabin and a structure for the net behind the cabin.

Fishing activities at the INP

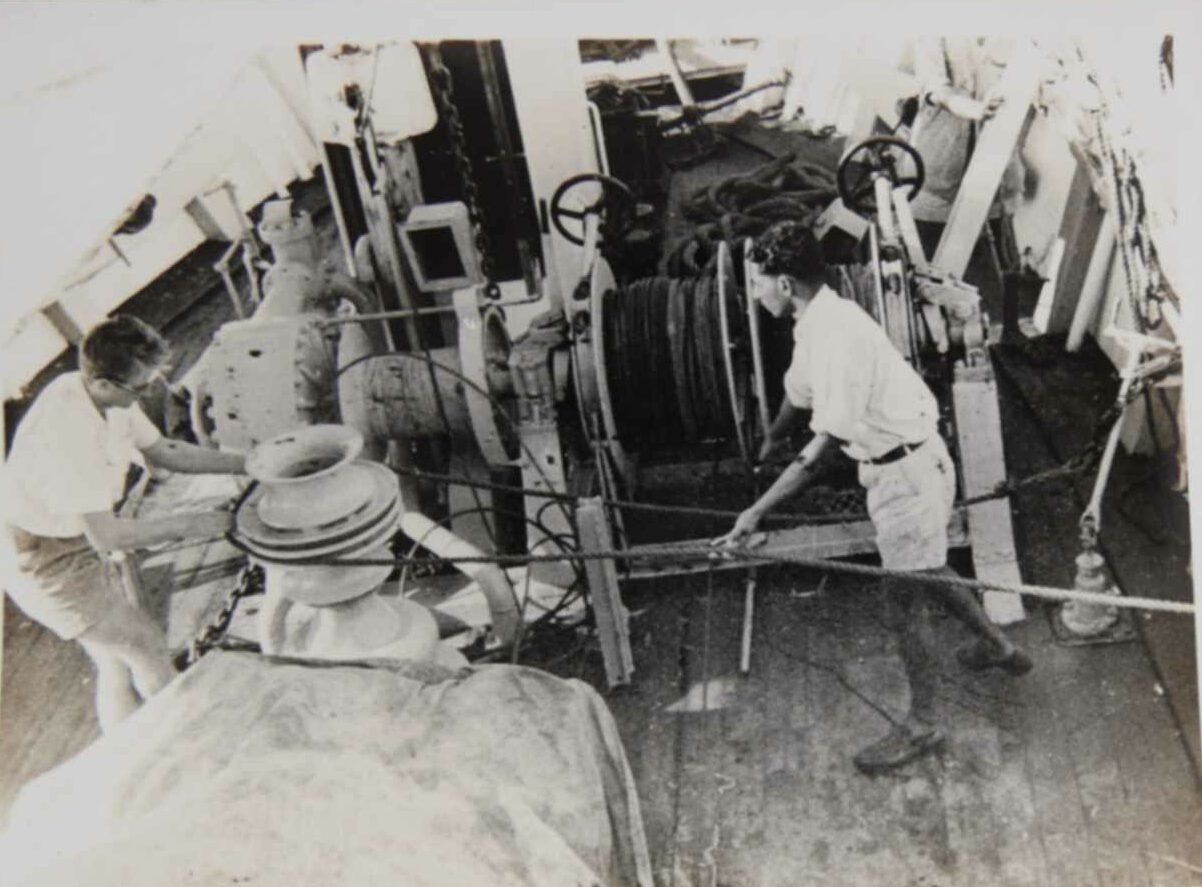

Fishing methods were modernised; winches and trawling were introduced instead of pulling the net by hand, allowing for offshore fishing. Boatmaking yards and a harbour were built. The project fishermen had various financial options to buy the new boats. The cotton nets used were replaced with synthetic nets, and supplementary gear was developed over the years.

Problems at Kollam

The INP attempted to introduce a fishing cooperative system in Kollam but encountered difficulties. Earlier, payment for the catch was made by the merchants when it suited them. With the motorised boats, the fishermen required working capital. Some boat owners established themselves as middlemen in the business, breaking traditional merchants’ monopoly.

The fishermen with canoes alleged that the sound of the motorised boats was driving away shoals. The sight of trawlers brimming with fish when the canoes could barely make enough for subsistence added to the hostility. Trawlers reported that on several instances, on their way back to the shore, 50–60 hostile canoes would surround their new boats.

Moreover, conflicts of interest emerged between fishermen and fish merchants, INP representatives and fish merchants, Nairs in administrative roles and Latin Catholic fishermen. Members of the Araya community struggled to adapt to the new fishing methods and sold their boats to the Latin Catholic fishermen in a few years.

“The ice factory there has been repurposed as a shark fin extraction unit” … Ravinath, former deputy director, NIFPHATT

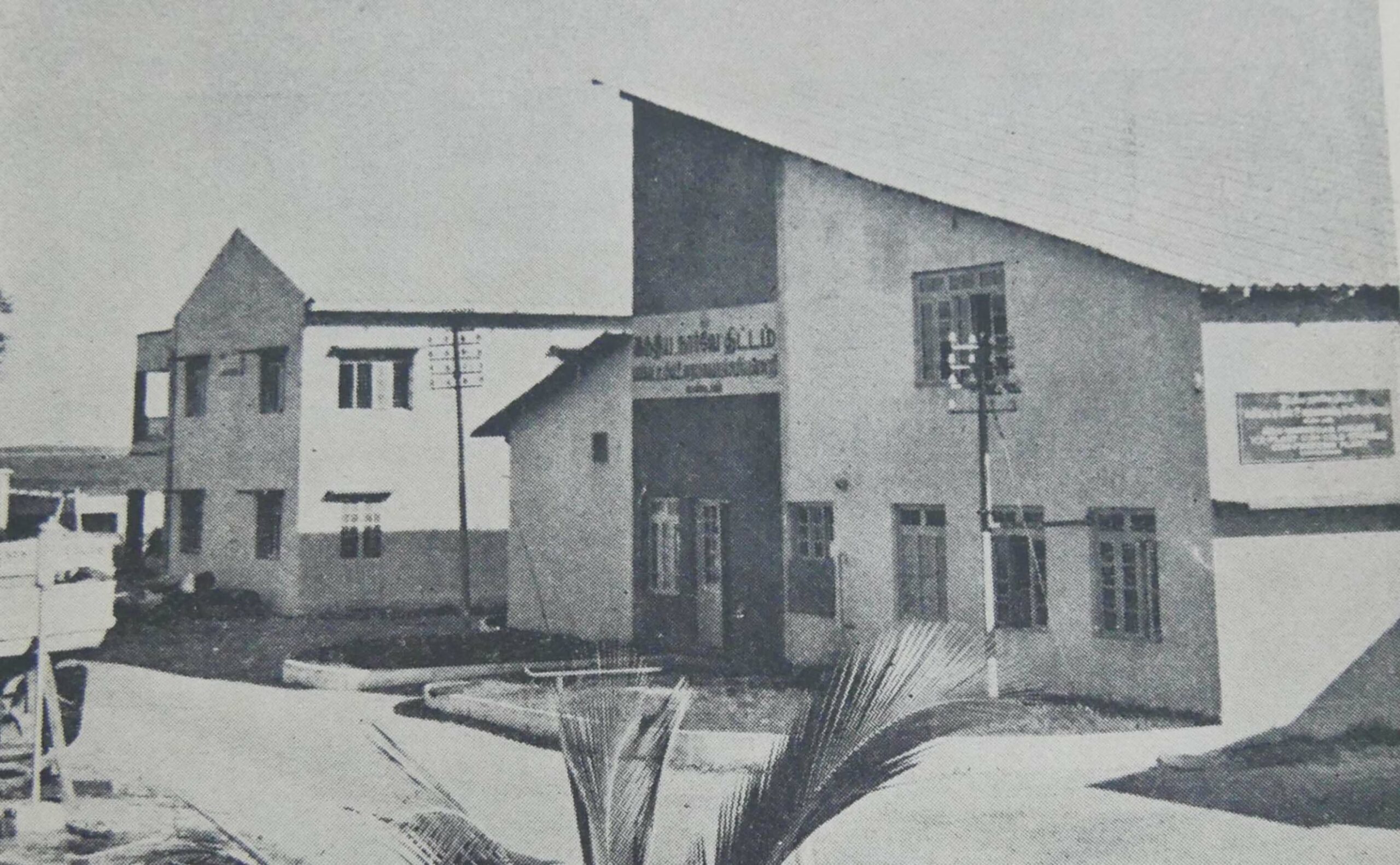

When the INP was moved to Kochi, the buildings at Kollam were given over to the state government. Chitraranjen, a skilled labourer who works at the Kerala State Coastal Area Development Corporation, which now owns the original INP office site, mentioned that when the building was being renovated in the recent past, the excavator could not break the base; rather, the teeth of the machine broke. Hence, the new building was constructed on the existing base.

During INP, private entities entered the field of fish processing and export. One such company, Kerala Sea Foods, located near the Neendakara bridge, still exists in its original location.

“The Norwegian techniques increased fish landings. There was excess fish, and to teach the fisherfolk how to handle this, the project was moved to Kochi where there was already a fishing research institute and harbour,”… Varghese John, Marketing Officer, NIFPHATT.

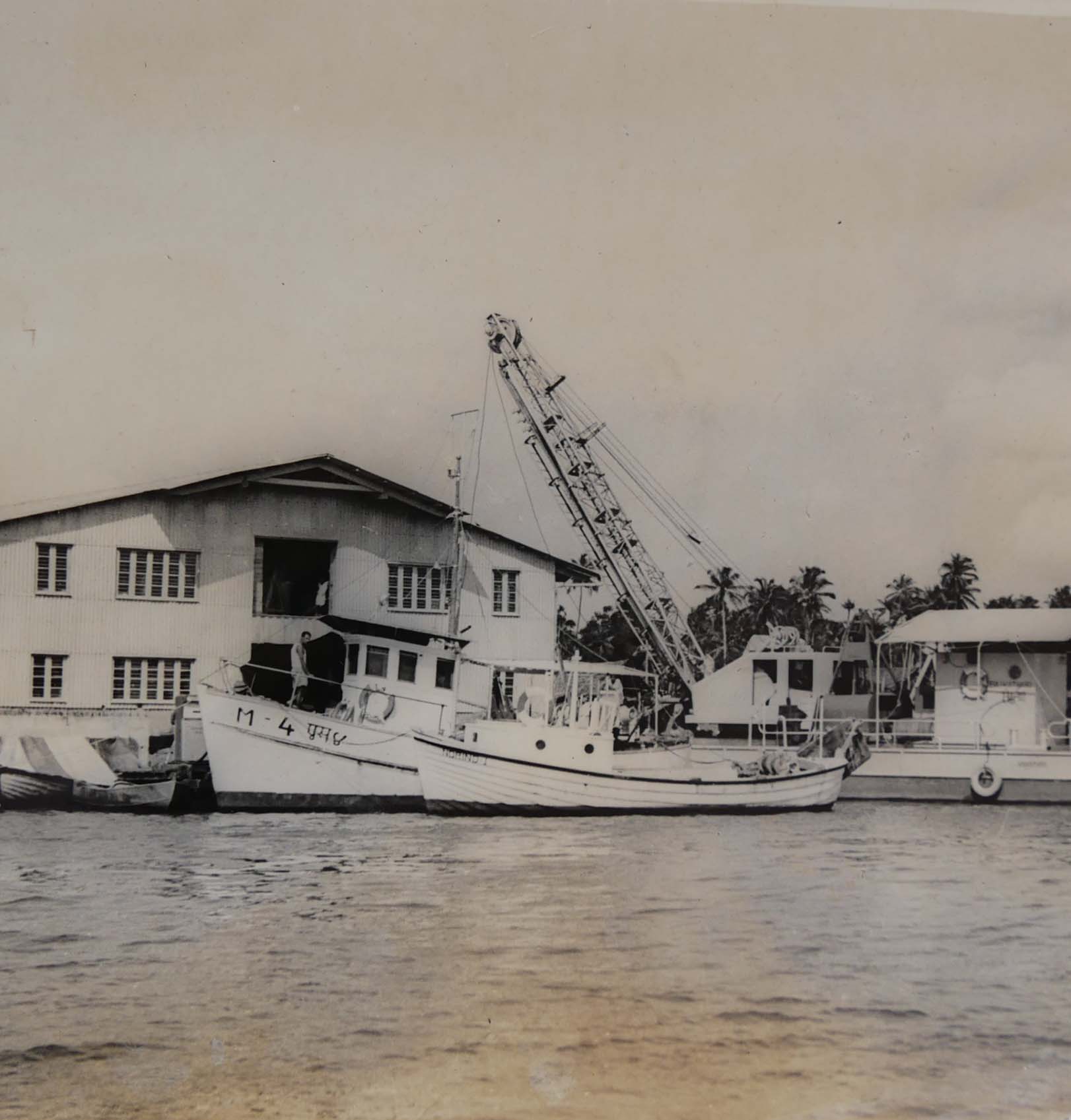

In April 1956, an agreement was signed to expand the project to Kochi. The idea was to conduct fishing experiments with bigger boats. The project was located in an existing fishing hamlet in Ernakulam. A modern, integrated fisheries complex was created. This involved introducing larger fishing vessels, establishing onshore facilities like ice plants and refrigeration units, creating maintenance infrastructure for large vessels, and organising marketing operations. The Kochi base focused on offshore fishing activities and conducted scientific studies on the area’s fishery resources.

“The dry docking and repair yard constructed during the INP is still working. The rails, the winch, and the dredging machine have been maintained and are in use in Ernakulam.”… Varghese John.

A dock was constructed at the Kochi office, and the INP vessels started using it. The project also built a dry docking yard with a slipway to repair vessels. “The quality of the materials that the Indo-Norwegians used was excellent, and the central government ensured that they were maintained,” said Varghese.

“Until the INP, there was no slipway here. The slipway at the Shipyard came later. The ships had to be lifted through some other difficult mechanism. The slipway at the INP had a 250-tonne capacity with eight berths. It was shared with the fishing industry. It was useful for boat builders and owners at that time,” added Ravinath.

Did the INP build all the boats for the projects in India?

Not really. Three Norwegian fishing schooners equipped with automatic pilots, radios, telephones, echo sounders, fish finders, and cold storage arrived in January 1955 to support fisheries research. The schooners surveyed the coastline from Cape Comorin to Kozhikode, collecting data on weather conditions, surface temperatures, currents, and fish availability. The knowledge and experience gained from this project led to its expansion in terms of its functions and geographic reach in subsequent years.

In late 1956, four medium-sized boats, M-Boats, were brought from Norway to Kochi. These boats played a crucial role in training Indian fishermen and assessing the feasibility of fish and prawn trawling operations. Initially, Norwegian fishermen operated these boats, but as Indian fishermen gained expertise, the number of Norwegians on board decreased.

Research at Kochi

One of the schooners from Norway was converted into a fishing-cum-research vessel, and numerous research expeditions were conducted off the Malabar coast, including the Laccadive. It could accommodate a crew of 17, including four scientists. Three different laboratories were available on the ship: two analytical laboratories and one sampling laboratory. Additionally, there was a small room designated for fish processing. All laboratories were equipped with electric power and hot and cold water, with one laboratory having access to seawater.

“The shore determines the size and shape of the boat. The net for demersal (bottom of the sea) fishing would be 1–2 km away. It is dragged through the bottom, and if there is any rock, it may break the net or tilt the boat. The project did the necessary experiments and establish which kind of boats needed what kind of net and gear. The establishment of ice factories, freezing plants, and processing units were also done under the expert opinion of the Norwegians,” said Ravinath.

“Pelagic fish are those that stay close to the water’s surface. Knowing the temperature was important because it would tell you at what temperature a particular kind of fish could be found,” added Ravinath.

When did the INP start offices in other locations?

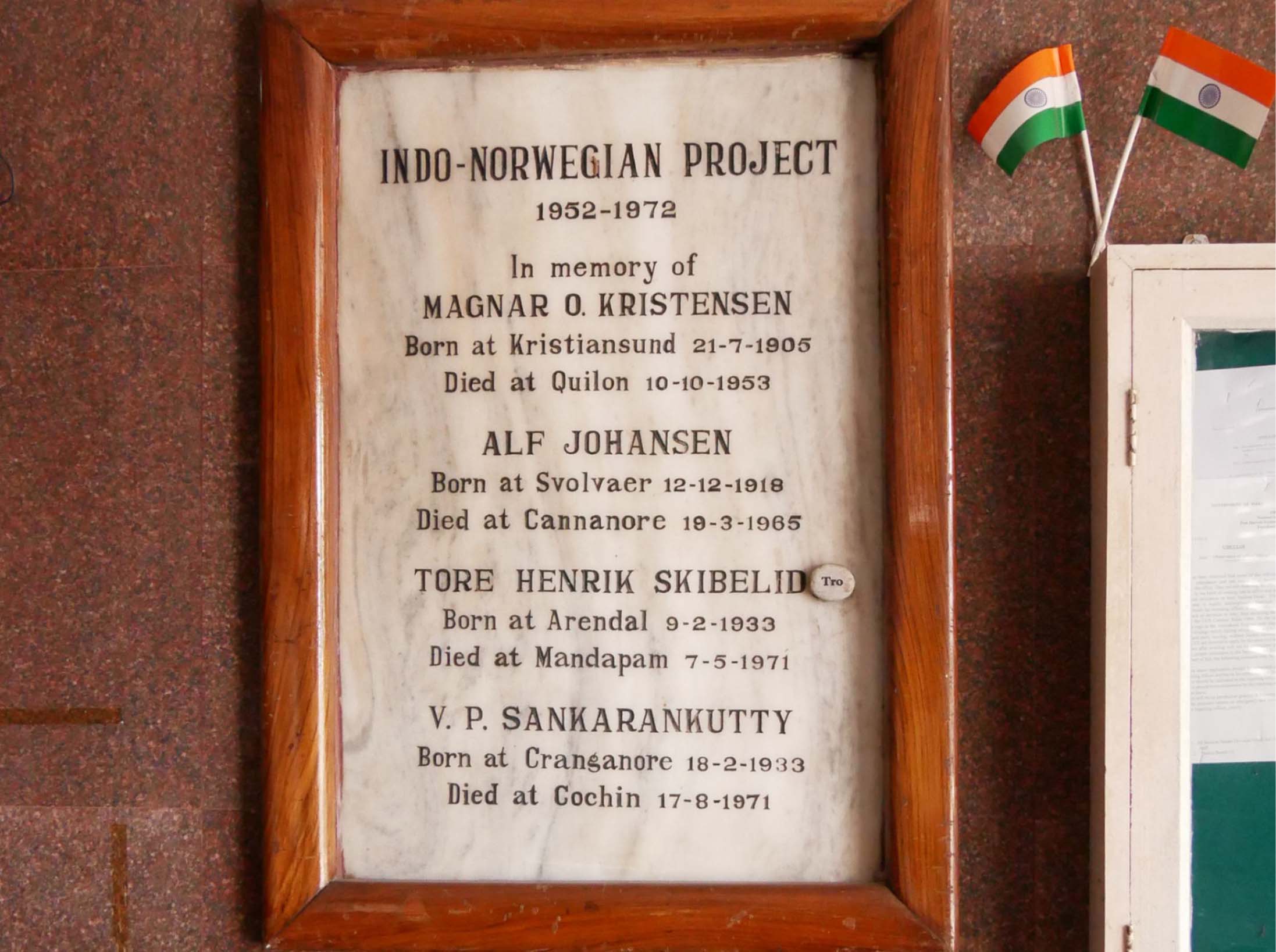

Units were started in Karwar (Karnataka), Kannur (Kerala), and Mandapam (Tamilnadu) in 1963. Sales units were started in Bengaluru and Chennai. The other centres were handed over to the respective state governments when the agreement involving direct Norwegian involvement in the project ended in 1972.

The Norwegians

“It was a wonderful time. There would be parties for every occasion, Christmas Eve, and so on. They would invite us.” … K. Ravinath, former deputy director, NIFPHATT

When the Norwegians were in residence, they were given separate living quarters near the INP office in Kochi. The buildings are still in existence and used by NIFPHATT.

“It is said that the tapping sound could be heard when they danced on the wooden floor. When I joined, the floor had been replaced with mosaic, and the current floor was laid recently,” said Varghese.

“There was no differentiation among the Norwegians regarding work,” Everyone pitched in to do whatever was required for the project’s progress.”… K. Ravinath, former deputy director, NIFPHATT

Varghese John mentioned that most of the children of the Norwegians used to study in places like Ooty. They would come to Kochi during vacations, and programmes were arranged for them.

The Norwegians stayed for 2–3 years and returned to Norway afterwards.

They were sent to India on deputation by the UN. A new person would arrive when an existing scientist or technician left. A few of the Norwegians passed away while in India. Their bodies were taken back after embalming. “The embalming process was a bit difficult because, in the 1960s and 70s, the process could be done only in a few places in India,” said Varghese.

The End of the INP

In 1972, the second supplementary agreement between India and Norway ended. Despite the termination of the agreement, Norway assisted India’s fishing industry by providing equipment, machinery, and expertise for a few more years.

Undoubtedly, the Indian fishing industry would have developed differently and slowly if not for the INP and the developments that followed it. However, the reduced number of fish landings on the Kerala coast reminds us that generating awareness about sustainable fishing practices among the stakeholders is the need of the hour.

“People are badmouthing the INP now. The project brought in mechanisation. This, in turn, led to overfishing. But, how people utilise technology for good or bad depends upon them.”

– Varghese John, Marketing Officer, NIFPHATT, 2023