Rail and Tree: The Story of the Cochin Forest Steam Tramway

British colonialism in the Indian subcontinent was driven by the accumulation and exploitation of natural resources. To serve the infrastructural needs of the early years of British rule, primarily the expansion of the railways and shipbuilding, the pristine forests of the Indian Subcontinent were prospected for their timber. They aimed at creating a monopoly, supported by the compliance of the local governments, to prevent smuggling and competition, facilitating transport and reserving forests and plantations for felling timber.

Controlling the forests

The Forest Research Institute in Dehradun methodically documented the biodiversity of the subcontinent, deducing the specific qualities and utility of each tree as well as the communities dependent on these natural resources. Identifying that the forests of Cochin contained valuable timber the Company desired to exploit interior parts of the forest under the pretense of infrastructural development.

In order to secure timber for the Company the First Indian Forest Act was passed in 1865 allowing the British to establish control over the forests by declaring them as State forests, demarcate Reserved and Unreserved Forests and list Reserved Trees. Subsequent Acts and amendments consolidated British hold over timber, establishing the notion that forest use by the local villagers was not a right but a privilege. The Indian Forest Acts paved the way for the British to have a commercial monopoly over the forests in South India.

Timeline of Early Colonial Forest Policy

Timber resources of Cochin

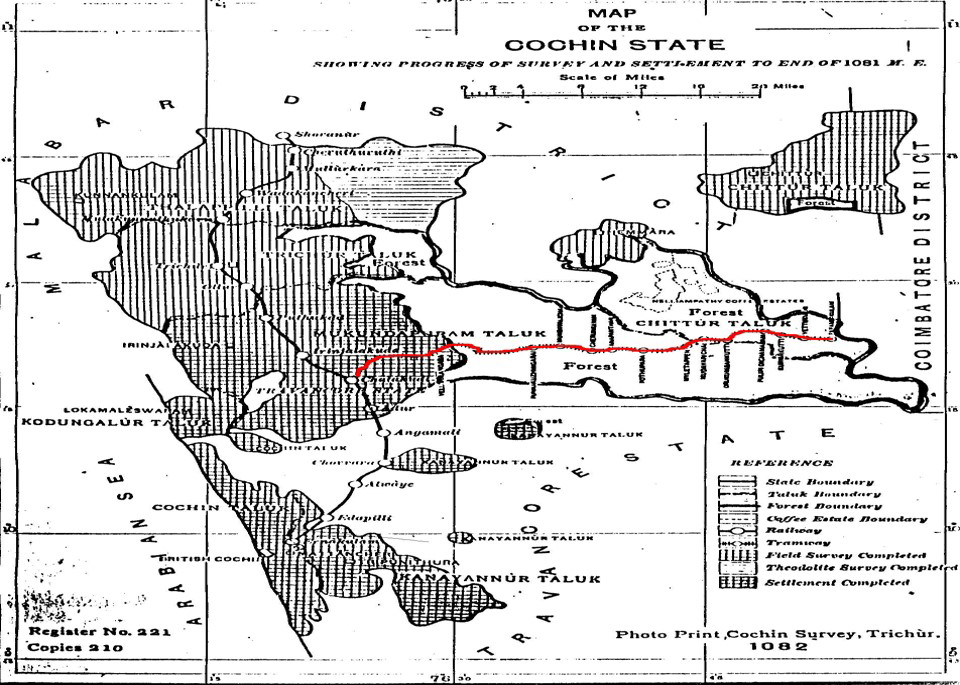

The forest policies in Cochin worked in conjunction with the local rulers’ compliance. Raja Rama Varma, Cochin’s monarch, was fascinated by the departmental system of the British and frequently discussed issues such as the smuggling of timber into Trichur and Ollur and the massive felling of teak trees at the Chittur Kanam (Chittur forests).

These actions culminated in the formation of the Cochin Forest Regulation which stressed the importance of appointing foresters and the need for adequate transport facilities to access the Parambikulam forest

Timeline of the Cochin Forest Steam Tramway

Plan for a Tramway

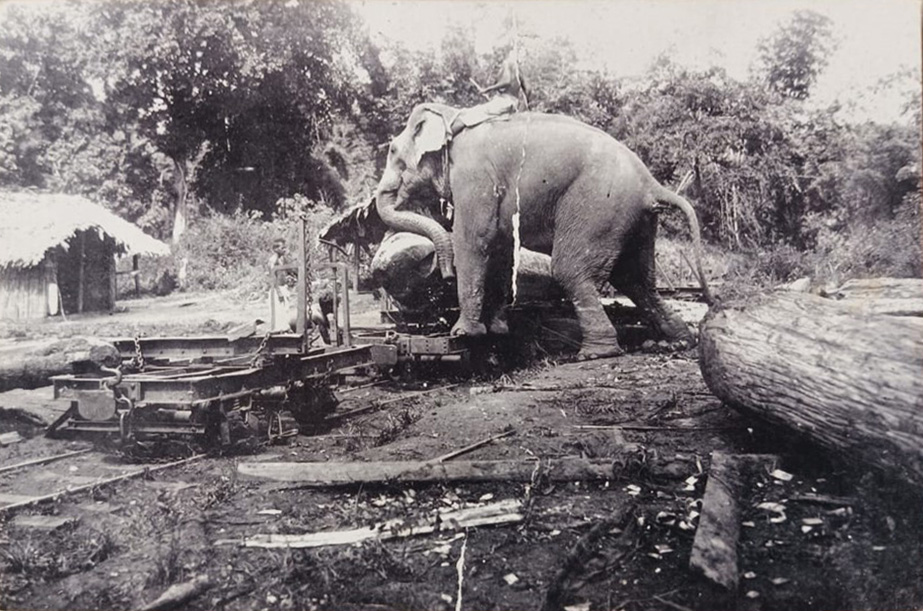

Transportation of timber to and from the forests posed some challenges. The conventional method for transporting timber used elephants, which became obsolete due to their inability to drag logs to the depots. Initial proposals included opening cart roads to facilitate continuous supply to and from the forests.

Another possibility was utilising the Chalakudy River as a transportation channel. Robert E Haffield was appointed in 1900 to survey and report the possibilities of this proposition. The report discovered that the higher ends of the river were full of hurdles and a land route with suitable transportation would tap a longer and richer forest region year-round. In the end the Parambikulam tramway was proposed with the recommendation of JC Kolhoff.

Building the Tramway

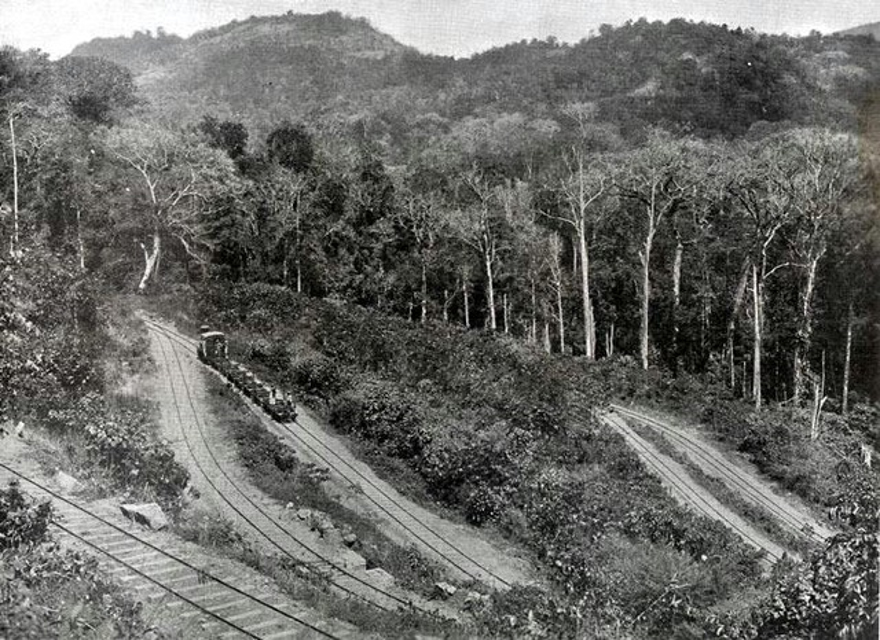

The work began in 1901 and was completed in 1907, designed to work the virgin forests of Parambikulam and Orukomban. It covered a distance of 83.20 km from its starting point Chalakudy at an altitude of 2700 feet above sea level. It remained a significant mode of timber transportation from 1907-1960.

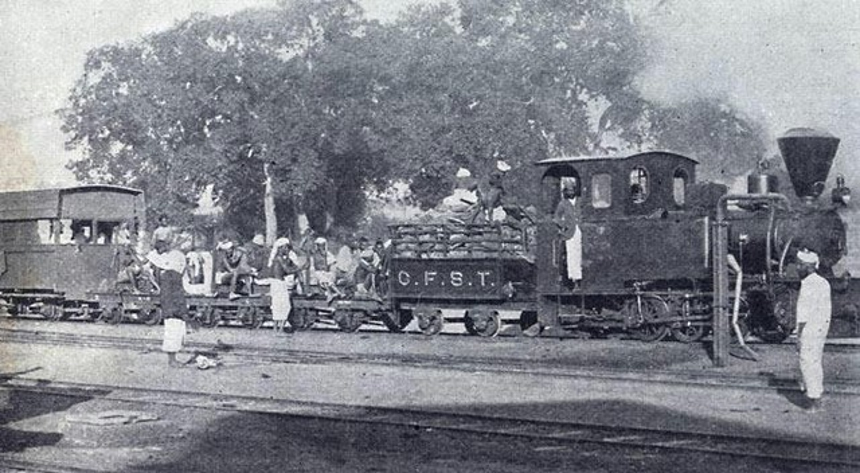

The main block of the forests worked by the tramline was the Parambikulam area. Private traffic was also allowed as the tramway transported fuel, canes, reeds and sleepers extracted by private contractors

The rolling stock of the forest tramway consisted only of open bogie trucks designed for carrying timber swivelled bolsters and chilled cast iron wheels, with a carrying capacity of 12 tonnes. It was supplied by Orenstein & Koppel.

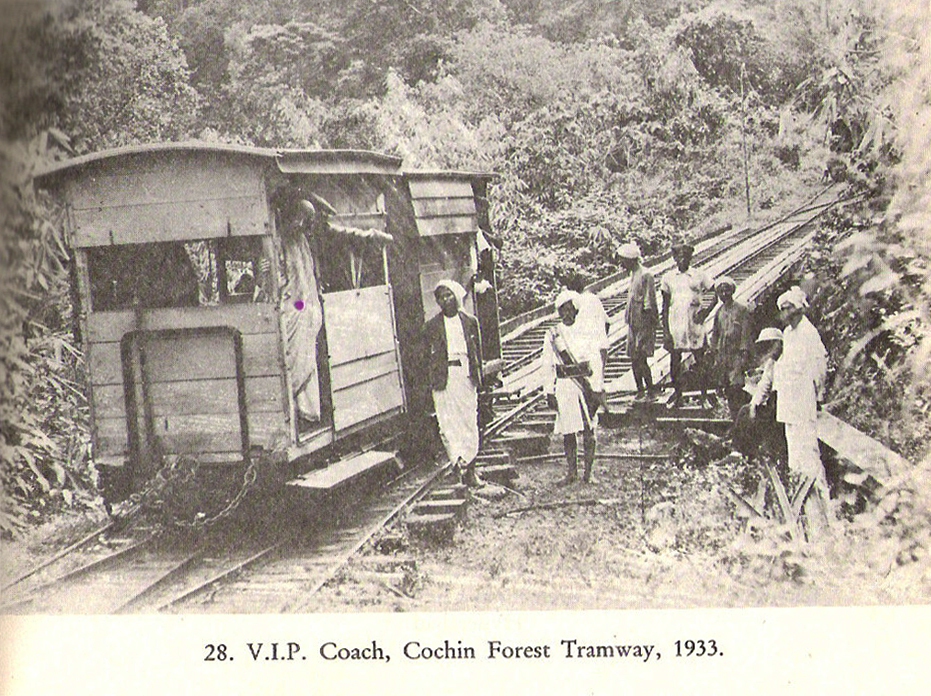

All the sections had steam engines alongside 70 open wagons and 2 bogies. It was designed uniquely with deep inclines, zigzag lines, brake houses, and turn plates, totalling 49.5 miles

Madakkuvazhikal

The unique zigzag curves through which the tramway ascended and descended the mountains were known as the Madakkuvazhikal. The workers referred to these curves as ‘three points climb up’ and ‘two points climb down’.

In these climbs, the train moved through an extended line to an endpoint and started moving backwards in reverse, rolling along the main line until it reached another reverse point. These movements took the train up and down the climbs.

In the final section, the train ran from Komalapara to the last point at Chinnar in the Parambaikulam range. The line passed through the five zigzag lines and descended to Mylappadan.

Staff

The Tramway staff consisted of Permanent Way Inspectors, Loco Foreman, Drivers, Strikers, Traffic Inspectors, Guards and Brake Coolies in addition to the administrative staff. The Tramway Department also established a full-fledged workshop at Chalakudy to produce spare parts and maintain the system. Tribals like Kadars and Malayars were employed as watchers and coolies in the tramway service. Hence, the tribal population were exploited as accomplices in extracting the forest wealth.

The Tramway itself was under the control of a tramway engineer who was directly responsible to the Diwan and held a special position in the Cochin Legislative Council, an elected body established in 1925.

Ecological Destruction

Some members of the Cochin Legislative Council were opposed to the creation of the tram system for fiscal and ecological reasons. Catering to the imperialists and the absence of proper planning for extracting timber led to massive destruction of forests in Cochin State. Private agencies supplied larger quantities of wood to the British and large areas of forests were leased out to private European landowners to start plantations. The expanded tramway which connected Ernakulam and Thrissur through the rail line in 1909, increased the felling of trees.

Furthermore, members of the Cochin Legislative Council exposed the smuggling of timber to the Malabar province and the wrongful imposition of taxes on tribals for collecting bamboo from the forests. In response, the Conservator of Forests called the tramway ‘a necessary evil’, till the state obtained all the timber of the Parambikulam forest, indicating the desire of the Empire to continue the tramway’s functioning. The system would become crucial for the British during the Second World War.

Backlash and Resistance

Agitated over the irregular functioning of the Forest Department and the continuation of the tramway, the council members moved several motions to reduce funding for the Forest Department and tramway.

C A Ouseph, the elected member from Chalakudy, attacked the colonial forest policies and questioned the prolonged working of the tramway after deviating from its original plan. Despite the strong resistance from the non-official elected members, none of the motions came to fruition as the native state was under heavy pressure from the British government. The tramway was to be expanded to exploit untouched forests in Parambikulam and it was proposed that work of the tramway be leased to private companies.

While the tramway was already an ecologically destructive entity, it became a profitable concern for the British during the second world war. Backlash continued in the following decades but the tramway was never discontinued by the Cochin State.

Timber for War

India was the only supplier of timber to the Middle East and the allied forces in Iraq and the Persian Gulf. Cochin became the supplier of timber necessary on the front for both world wars. In 1940, a Timber Directorate was set up in Delhi to channel the supplies of forest produce. The Annamalai Timber Trust and the Bombay Burma Trading Corporation were some of the companies that were given licences to cut trees which led to the severe destruction of evergreen forests in Vazhachal and Peringal. The strategic value of Indian timber during the world wars necessitated the destruction of the forests of the Cochin state

Timber and Shipbuilding

The South Indian Corporation built many ships for the British Navy. This revival of the shipbuilding industry was due to the continuous supply of sufficient timber and trained labour. This was an inevitable consequence of the imperialist policies of the British.

The Cochin Forest Department worked as a liaison between the Timber Supply Circle of Madras and the Timber Directorate of Delhi. This led to the allocation of extra funds and opening of roads into untapped forests, which were utilised by private contractors after the war, causing mass destruction.

Legacy of the Tramway

The tramway continued to function in Cochin even after Independence. With the formation of the state of Kerala, the relevance of the system was questioned and debated between the tramway staff and the Forest Department. Based on the report of the Chief Conservator of Forests in 1951, it was decided to discontinue the tramway as it was a financial white elephant. However, in 1953 and 1957 there were attempts made to revive or preserve the tramway for heritage and tourism purposes. Eventually the motion by the Forest Department to discontinue the tramway service was accepted, and the tramway was discontinued in 1963.

The construction of the tramway can be considered an engineering marvel for its infrastructural brilliance and how it manipulated Kerala’s unique topography to promote trade and industry of the colonial power. On the other hand, it is an example of the techno-ecological imperialism practised by the British to promote their commercial interests. The colonial policies played a detrimental role in changing and destroying natural resources, especially during the war which led to the loss of forest cover throughout India.