“Friendly ghost? Evil spirit? Mischievous goblin? Who is this Kuttichathan? It is an entity who can be good or bad.” - Mahalakshmi Prabhakaran, 2024

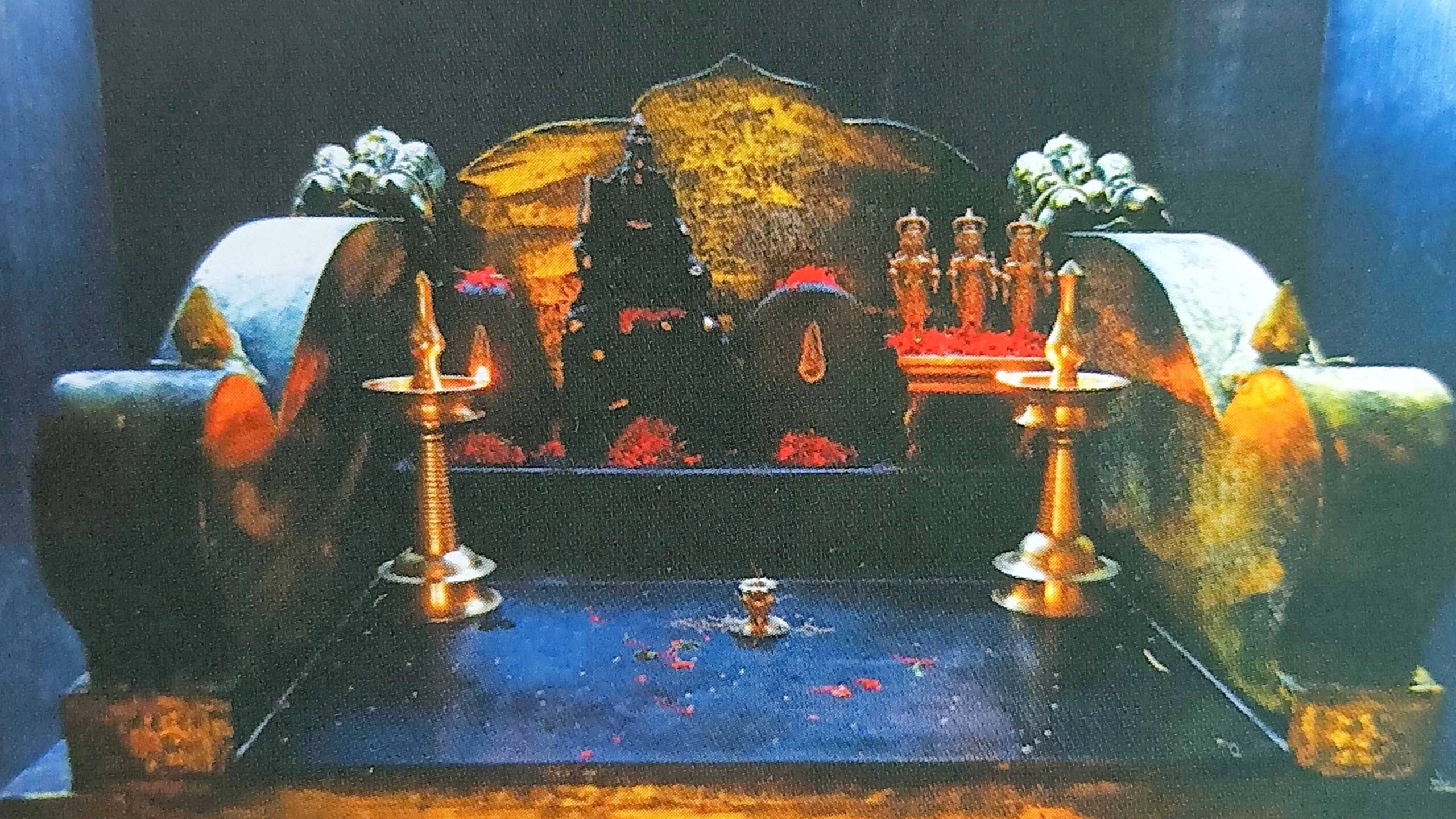

Legend has it that Vishnumaya was born to defeat the demon named Bhringasuran. A regional Hindu deity primarily worshipped in central Kerala, his divine abode is Peringottukara, a village in the Thrissur district. Vishnumaya, also known as Chathan is depicted as a nine year old boy wielding a kuruvadi (a slender weapon), and riding a buffalo.

Birth and Divinity

Disguised as sages, Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvathy travelled to the Kooli forests of Kerala, where the local tribe, the Malayans, offered them shelter. There, Shiva met the beautiful tribal girl Koolivaka and expressed his desire for her. Surprised by the request, Koolivaka used the excuse of her menstrual period to delay the encounter. In response to the chaos caused by the Asura Bhringasuran, Parvathy disguised herself as Koolivaka and united with Shiva, resulting in the miraculous birth of their son, Chathan who had the power to end the life of Bhringasuran. Koolivaka embraced her role as his mother and raised him alongside her other children in the forest.

As Chathan grew, Koolivaka revealed his true lineage and encouraged him to meet his divine parents at Kailasam. There, Shiva and Parvathy bestowed upon their son the knowledge of warfare and gave him two kuruvadikal to use in his forthcoming battle with Bhringasuran.

Perceptions of Chathan

Rejini Deepankuran shares a story from her great-grandfather’s time about a labourer who tried to steal plantains but found himself frozen in place. After being advised to sincerely offer the stolen fruit to Vishnumaya, he was released and rushed to the temple. Since then, his family has gifted a plantain bunch each year, as it’s said that no family worshipping Vishnumaya will face theft. Chathan’s actions often serve as lessons for those who neglected ritual worship.

Vishnumaya Chathan in Family Temples

The most noteworthy festival honouring Vishnumaya is called Kalamezhuthupattu. Kalasham is another important ceremony dedicated to Vishnumaya. While Kalam is a community event organised by the temple committee, Kalasham is sponsored individually and typically involves only the closest family members. One carries out a Kalasham with a particular purpose in their immediate life: to overcome an existing troublesome situation like a disease or a financial challenge or so on.

“The men in the family do the Kalasha-puja, while the women prepare food for Vishnumaya and the participants,” Rejini Deepankuran, 2024

“I’ve believed in Chathan since my childhood. I would wait to listen to stories of this entity from my grandma when we came to Kerala for our holidays. - Nitin Prathap, 2024

Chathan in Popular Culture

In the battle against Bhringasuran, Vishnumaya was wounded in his hand, causing drops of blood to fall. From this blood, 400 kuttichathanmar (little spirits) emerged to protect him from the arrows. Though ten arrows struck down ten kuttichathanmar, the remaining 390 spirits, alongside Vishnumaya wielding his kuruvadikal, ultimately triumphed, becoming the protectors of the Malayan tribe.

“Kuttichathan” translates to “little demon.” In Malayalam folklore, Kuttichathan is often portrayed as a mischievous spirit capable of granting wishes through puja and offerings, known as Chathan seva. While devotees revere “Chathan,” non-devotees often feel uneasy, associating the name with black magic. To teach lessons about neglecting offerings or troubling devotees, Lord Vishnumaya sends his minions to perform small disruptive acts—like dropping hair in food, throwing stones at houses, or moving sleeping girls to rooftops—while remaining invisible.

“My parents and I have heard of Chathan from the movies. What comes to mind when I hear ‘Chathan’ is black magic and a demonic figure. Through them we get the idea that Chathan is an evil and worshipped for immoral needs like making money unethically or killing the enemies.” - Antony, Kochi, 2024.

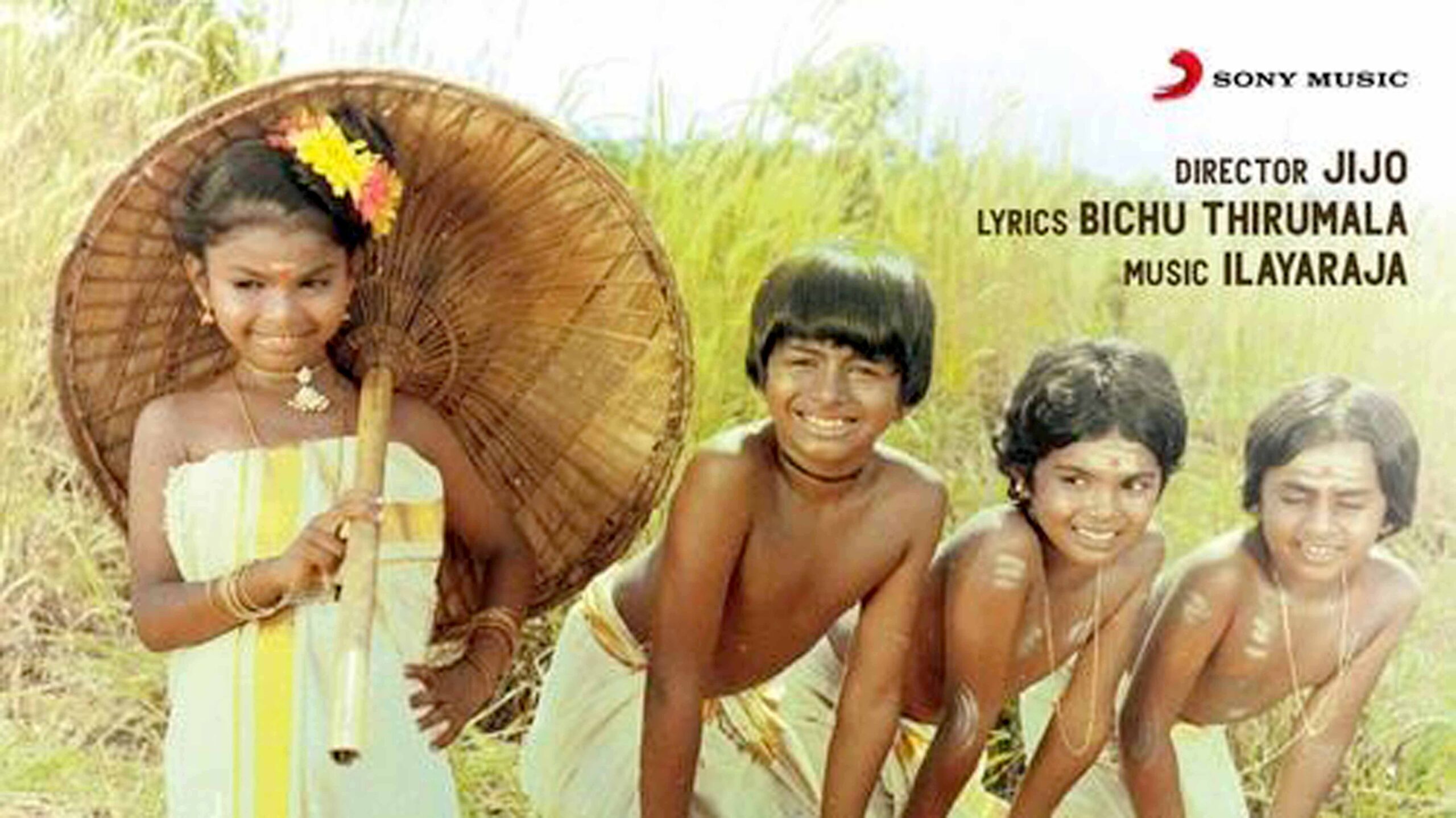

“The movie My Dear Kuttichathan and its TV series brought about a sense of safety, joy, fun, and friendship. But after watching Bramayugam, I can’t help but perceive Chathan as vengeful, cunning, and manipulative.” - Aravind, Thrissur, 2024

A More Scholarly View

LK Anantha Krishna Iyer describes ” Kuttichathan…is… like Shakespeare’s Ariel—little active bodies and most willing slaves of their masters who happen to control them… As for remuneration for his services, Chathan wants nothing but food. It is indeed a conflicting thought because although he could be a troublemaker, Chathan seems to be loyal to those who offer him food and respect”.

Nirmal Sahadev’s Kumari (2022) is a suitable example representing this. In it, the ‘good’ Chathan, called Illimala Chathan, assists those who provide him with food and have good intentions. Chathan is compelled to carry out his problematic acts due to orders from his ‘master’. Is he good or bad then? OnManorama, the English online news portal, describes Rahul Sadasivan’s Bramayugam (2024) and Jijo Punnoose’s My Dear Kuttichathan (1984) depict the manipulation tactics of power-hungry people who ensnare gods and demigods like Chathan, Karinkali, Yakshi, etc., exploiting their vulnerabilities to instil fear and exert control over fellow beings.

“I remember this character called Luttappi in the Mayavi comics in Balarama. He was this red-coloured, bald, little imp with two horns and a long tail similar to the portrayal in Bramayugam. In both, this figure is portrayed as someone who is deceitful and villainous.” - Sruthi, Kozhikode, 2024

Gilles Tarabout remarks about the confusion behind the name ‘Chathan’ in his work On Chattan, “I shall use here ‘deity’, but Chattan has also been variously described as a ‘spirit’, a ‘ghost’, an ‘imp’, a ‘demon’, and a ‘god’. The terminology itself implies a moral judgment— a condemnation, a disregard, a fear, or a devotional feeling, that is, socially and ideologically marked viewpoints. How then is the social scientist supposed to write about Chattan? I take the case of this deity only as an example, as I trust that the question equally concerns the description of many other ones.”

So, Reverence or Fear?

How can someone with such a mischievous personality be considered divine? Are gods not supposed to know what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’? Should a god not protect his devotees like a child instead of inflicting harm when they miss a day of worship? While the idea is not universal, different cultures have diverse religious practices. In cultures across the world, the notions of good and evil are not as black and white. They exist on a spectrum. While Chathan in popular culture may seem amusing, this topic is worthy of study within the context of the religious culture and the film culture of Kerala and how both impact Malayalis’ beliefs.

Gatha Durgadas in her article says that both her mother’s and father’s families hold different opinions about the deity, reflected in whether they worship him or not. And she intends to maintain a connection to both the inside and outside of the circle of worship. This duality allows her to approach the deity while recognising the complexity of human beliefs and the enduring power of faith. Chathan embodies the difference between a spirit with miraculous powers, capable of granting wishes and performing feats, and a mischievous spirit that requires careful appeasement to avoid disruptive consequences.