Bigoted Laughter

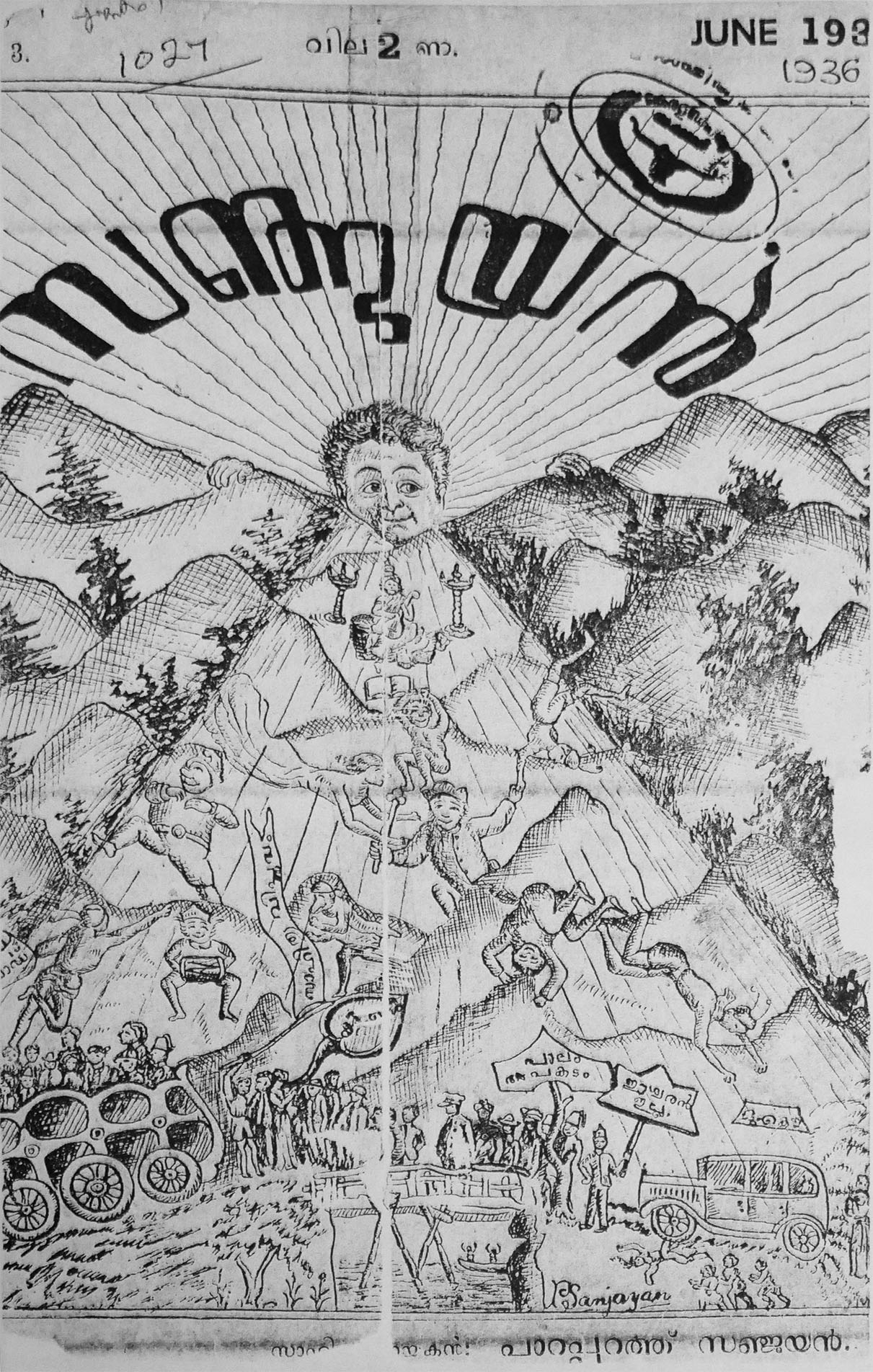

Political cartoons arrived after prose and poetry had satirised society and the government for centuries. Sanjayan’s quick-witted use of the language of laughter commented on the new forces and challenges to the cultural domains of ‘nation.’ His eponymous magazine introduced the Punch style of cartooning to Malayali imagination and paved the way for many Malayali satire periodicals.

The creatures in Sanjayan’s cartoon menagerie borrowed from Punch’s humour and placed them in incidents and anecdotes from Indian mythology. The characters represented the ruler and the ruled seen through descriptions of violence, injustice, want, famine, and pestilence according to contemporary political events. Other preoccupations were the caste system and the role of the Congress party in reviving the spirit of national movement. These, along with socio-political developments, like Marxism and Socialism in Kerala, were the themes of Sanjayan’s cartoons and essays.

Developing the Character

Inspired by two characters of Mahabharata, Vidushak, the irreverent but pertinent court-jester of Mahabharat, and Sanjayan, the divine ‘virtual’ spectator to blind Dhritarashtra, satirist Sanjayan creates a backstory in which he is exiled to a village in Malabar, to laugh at others and be subject to their slander as his punishment.

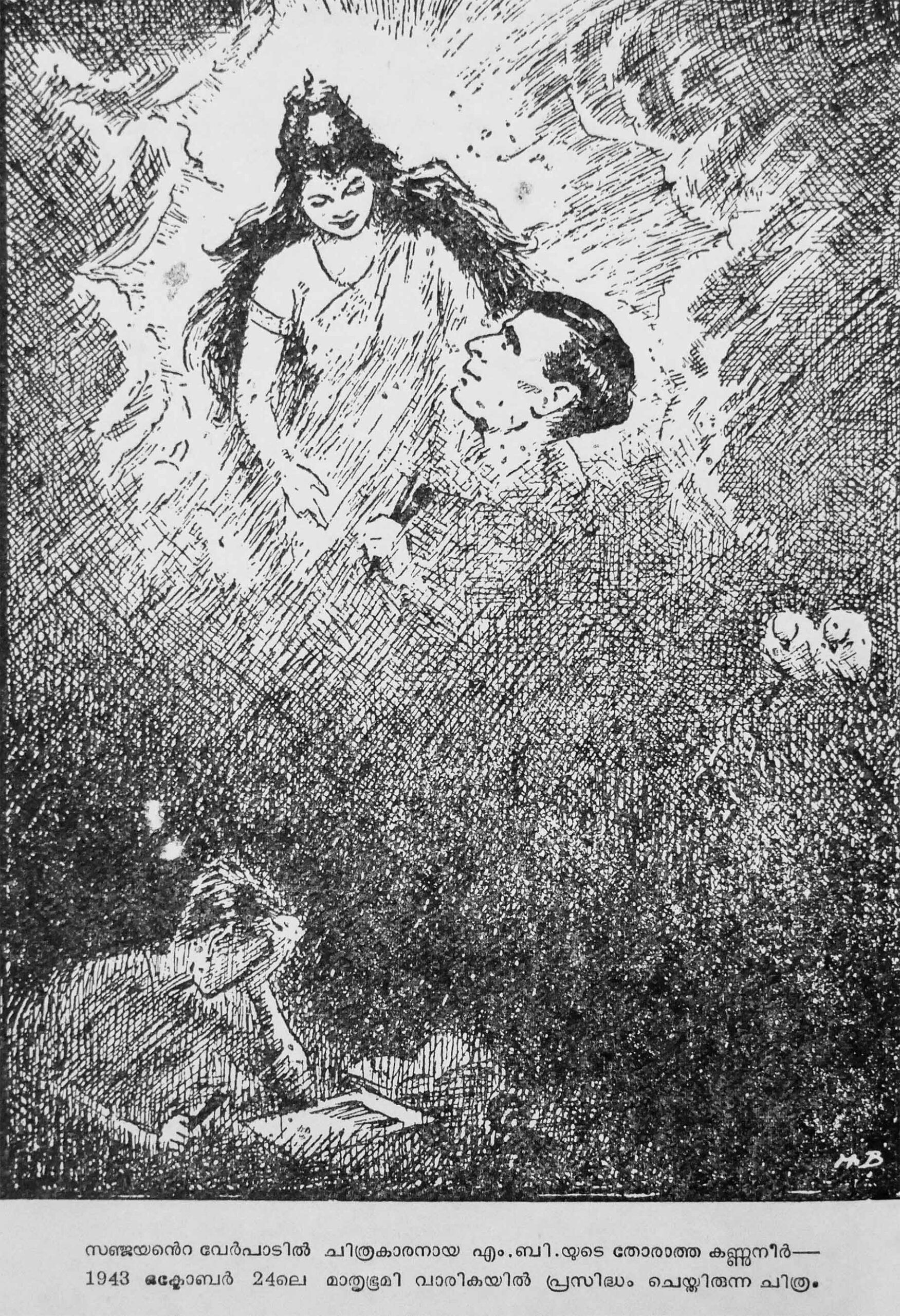

This imagery marked a unique experiment in Malayalam periodicals—an artist-editor collaboration between Sanjayan, the writer, and M. Bhaskaran, the illustrator.

Deceitful Socialists

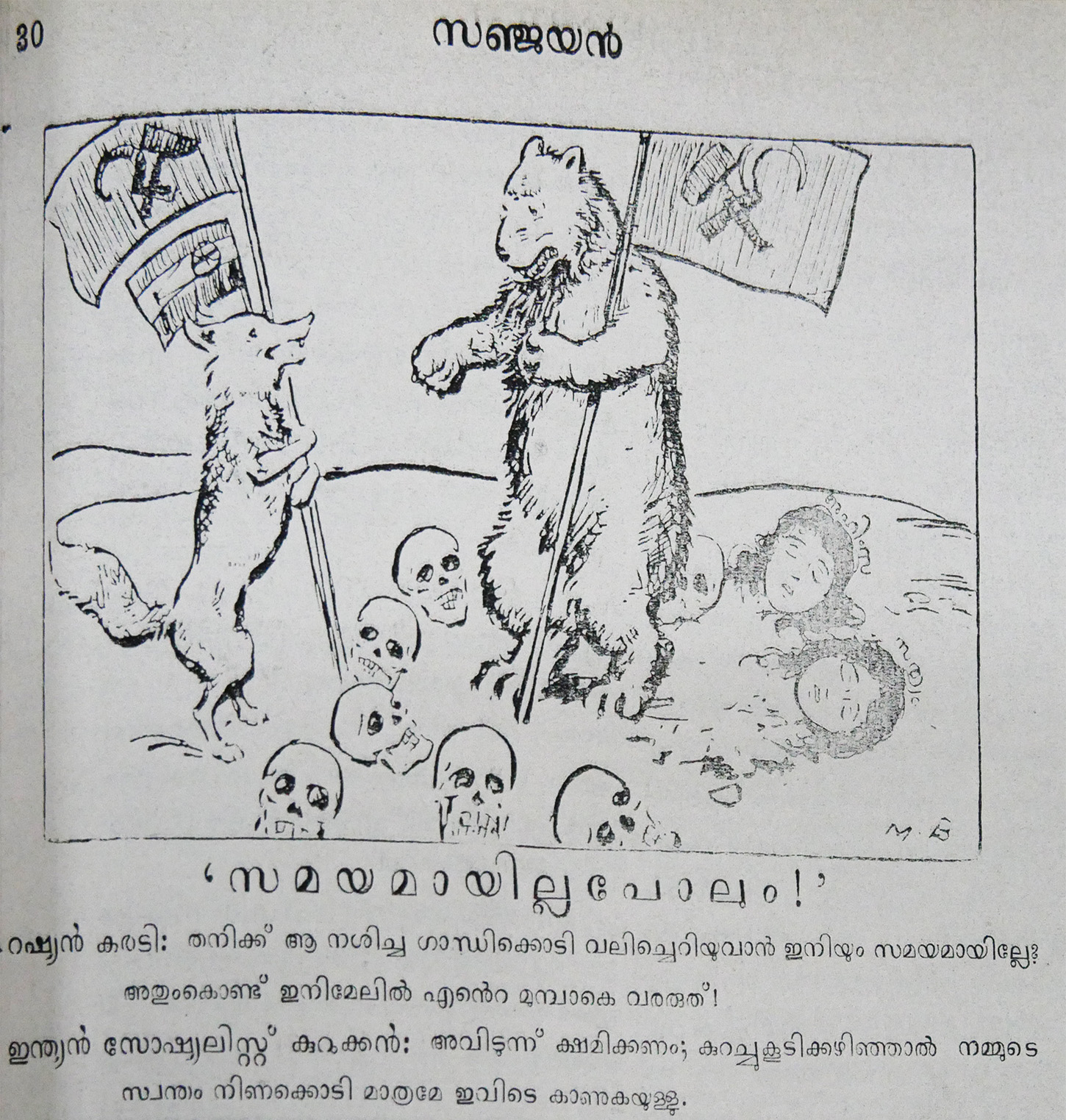

Diagnosing socialist realism, Sanjayan described a “Communist Plague” as a societal illness. He brought scathing attacks against socialists and their revolutionary mode of agitation. He also criticises socialists and ridicules their protests, agitations, and sensibilities to social problems, and sarcastically points out that they secretly believed in God even though they pretended to be all about logic and science. Their radical ideas are seen as duplicitous and the uncritical use of the term “bourgeoisie” (referencing the wealthy) is a symptom of this affliction. He even adds that “comrades” who are already involved in shouting slogans, distributing pamphlets, and attending protests and conferences are beyond recovery.

World Affairs

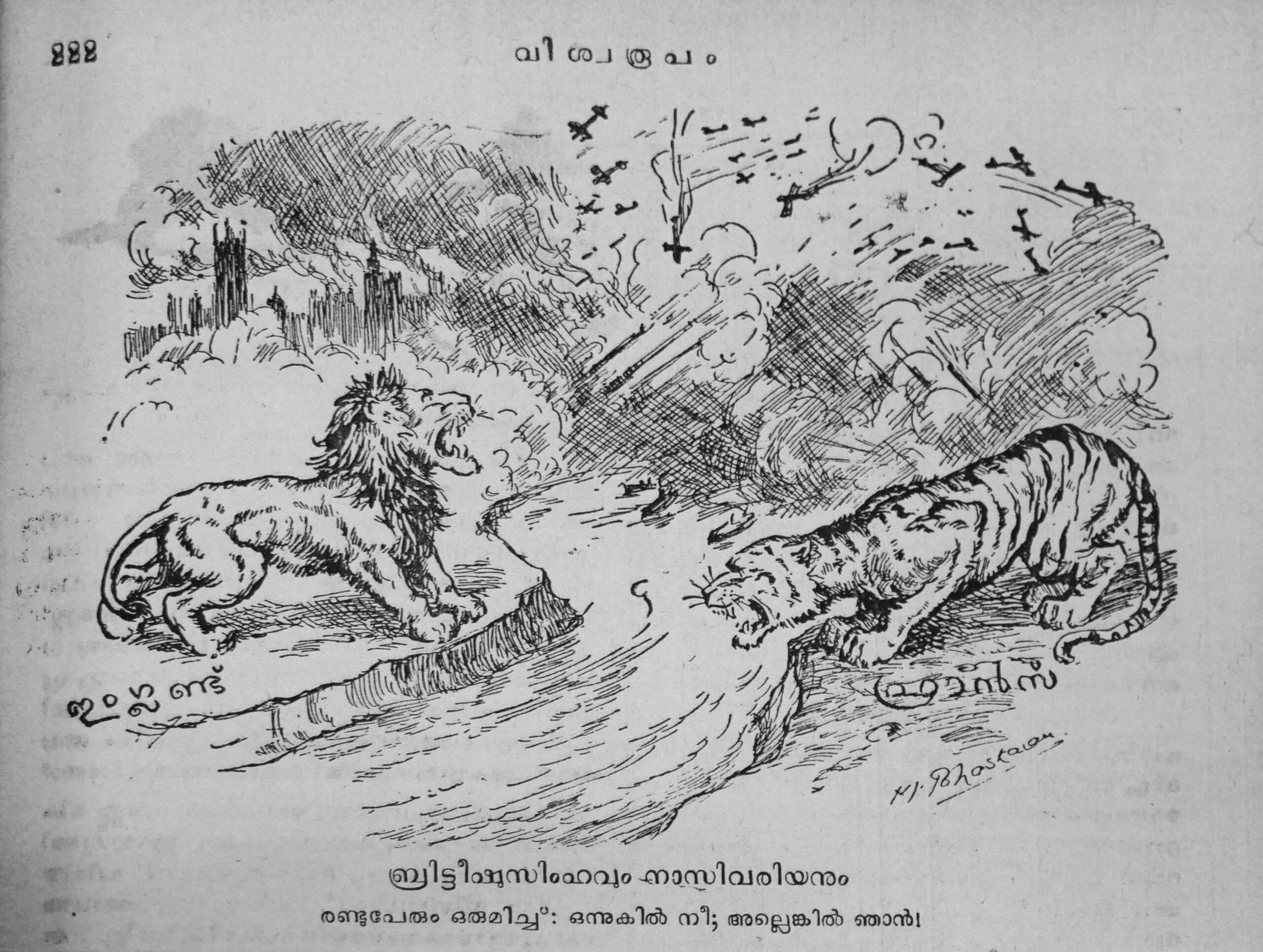

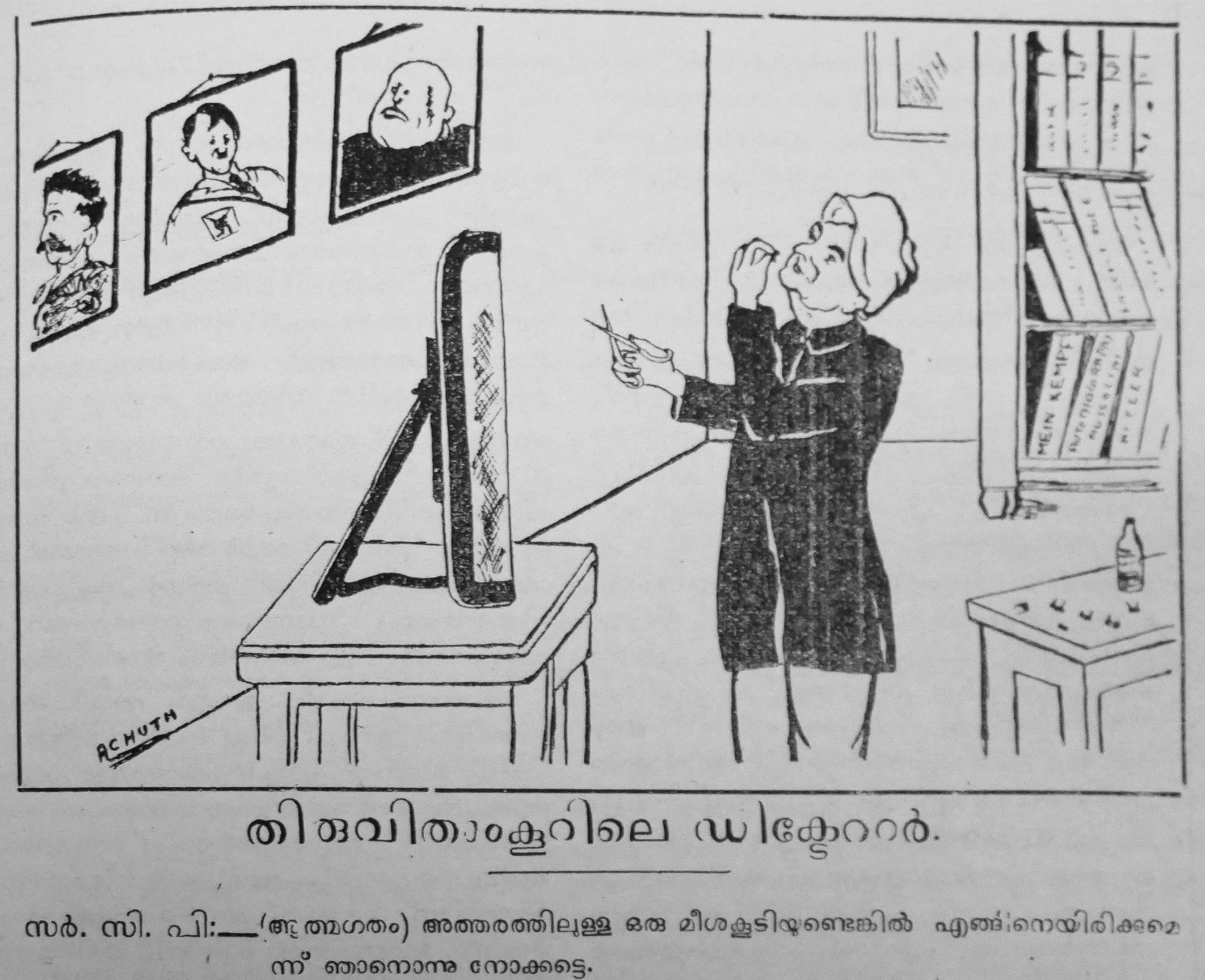

Sanjayan’s cartoons reflect his opinions and his reporting of World War II criticises the war, the fascist forces, and the declining power of Britain as a global power. The then-victorious powers represented Mussolini and Hitler as vicious and waggish creatures to depict the lack of humanity and rationality in their ideology. While this whimsical representation is similar to the Punch comics, Sanjayan depicts Hitler as a sinister evil force. Such depictions of Hitler and Mussolini, from whimsical creatures to grotesque forces of evil were also present in cartoons from other parts of the subcontinent.

An Eye on Kerala

Sanjayan adapted global happenings to reflect on and criticise power play in the Malabar Province and the kingdoms of Cochin and Travancore, navigating the political currents in the country that influenced these changes in Kerala.

He targeted government officials like C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, the Diwan of Travancore, notorious for his tyrannical rule. The local wing of the Indian National Congress had started protests against him and the communists even attempted to murder C.P. once and injured him.

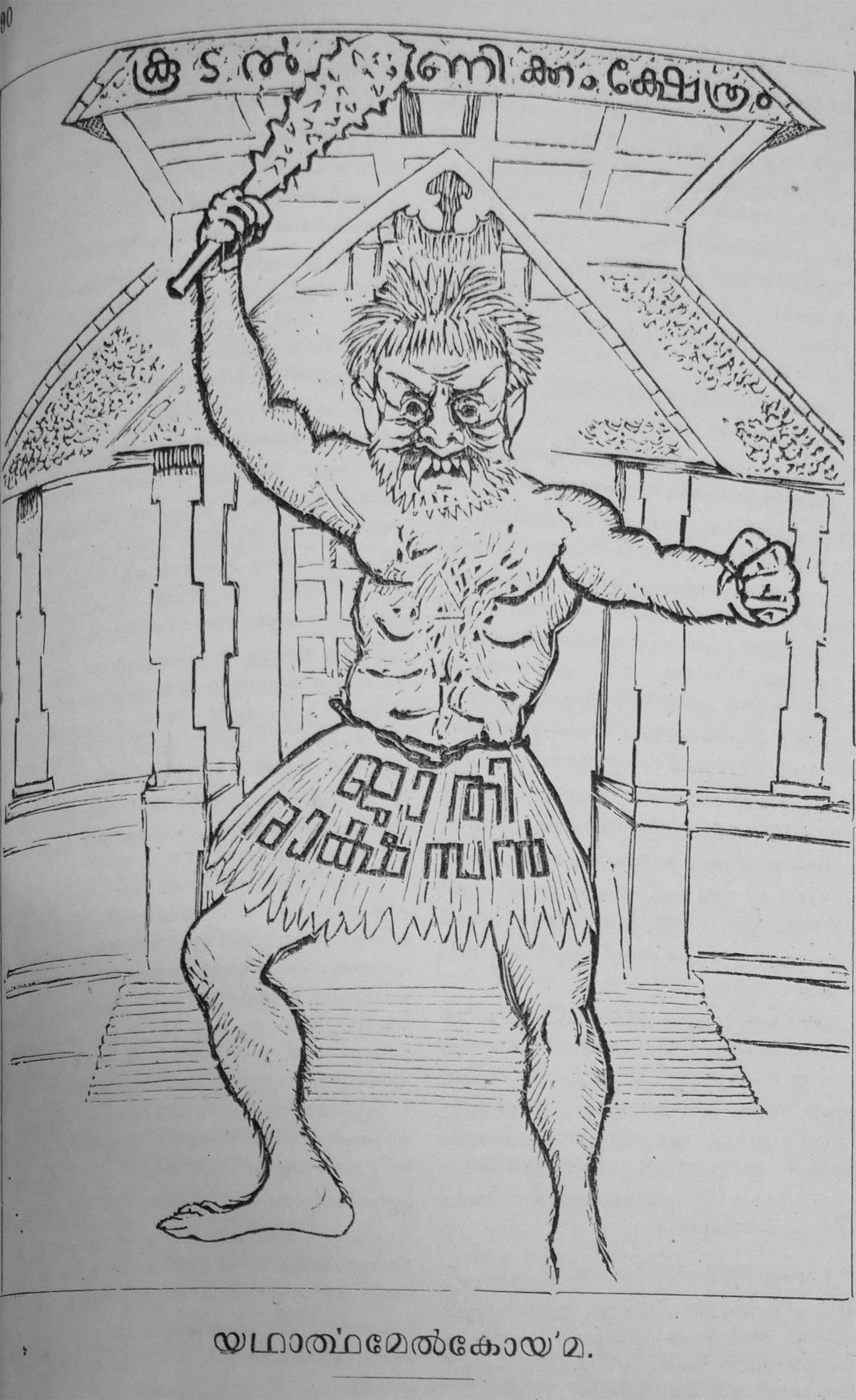

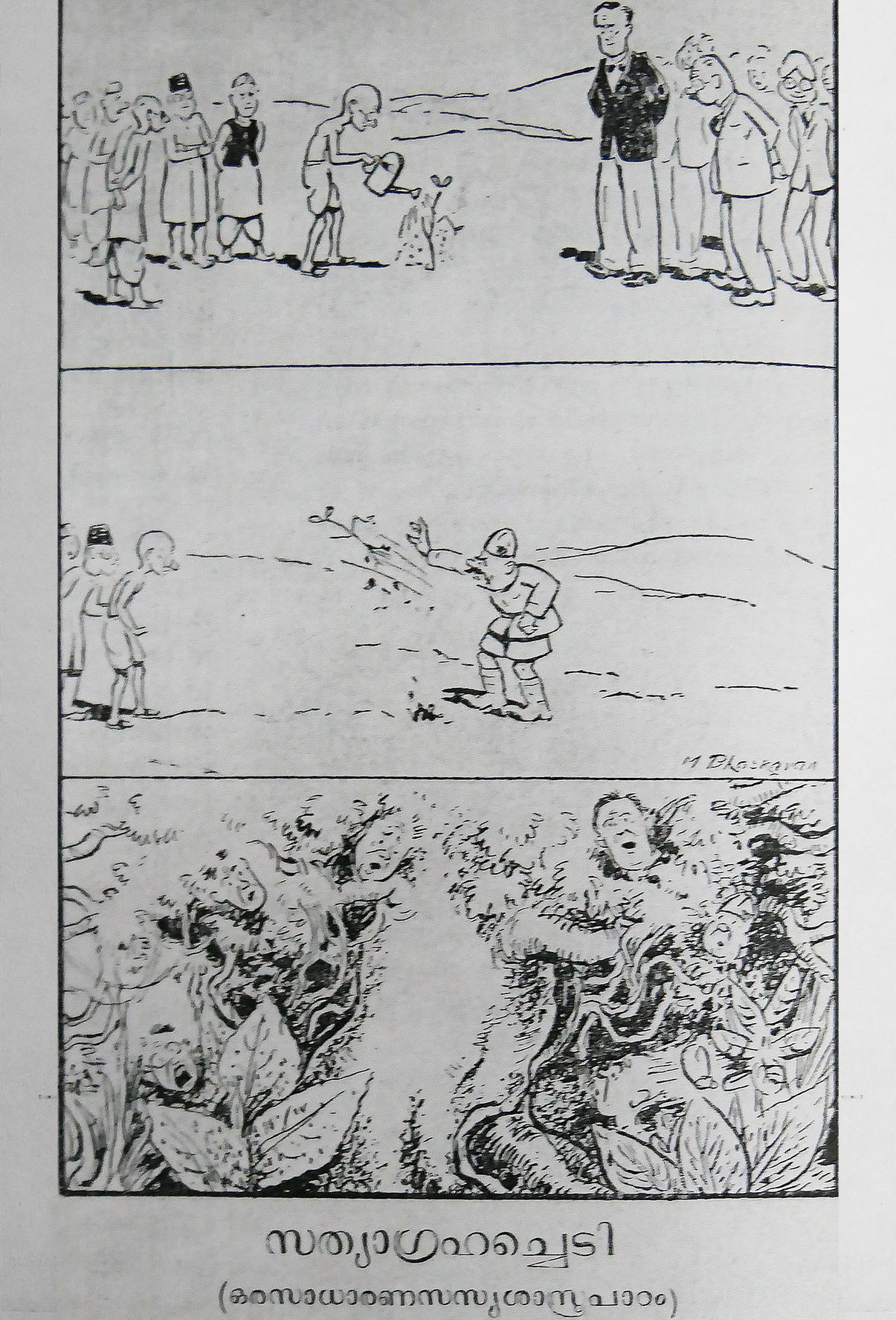

The Caste Rakshas

The caste system was a popular lampoon theme among early 20th-century cartoonists. Sanjayan reflects on these in Kerala, where the movements to revoke the ban on lower castes entering temple grounds were gaining ground like the Vaikom Satyagraha which was supported by Congress leaders, like Mahatma Gandhi, and anti-caste leaders, like E.V. Ramaswamy Naicker “Periyar”. In that sense, he developed an affinity towards Gandhi and supported Congress in the freedom movement.

Gandhi: An Antidote

By supporting Congress and Gandhi, Sanjayan paints Gandhism as the antidote to undo the changes brought by the socialists. He makes visible the difference between Gandhian and socialist ideologies. For him, Gandhian methods were rooted in spiritualism, and so, humane and holistic. However, socialism was devilish, its practices barbaric and brutish. Sanjayan’s laughter is not neutral, but partisan on many occasions. His support for nationalism is evident in the nationalist imagery he uses, the most significant being that of Bharat Mata.

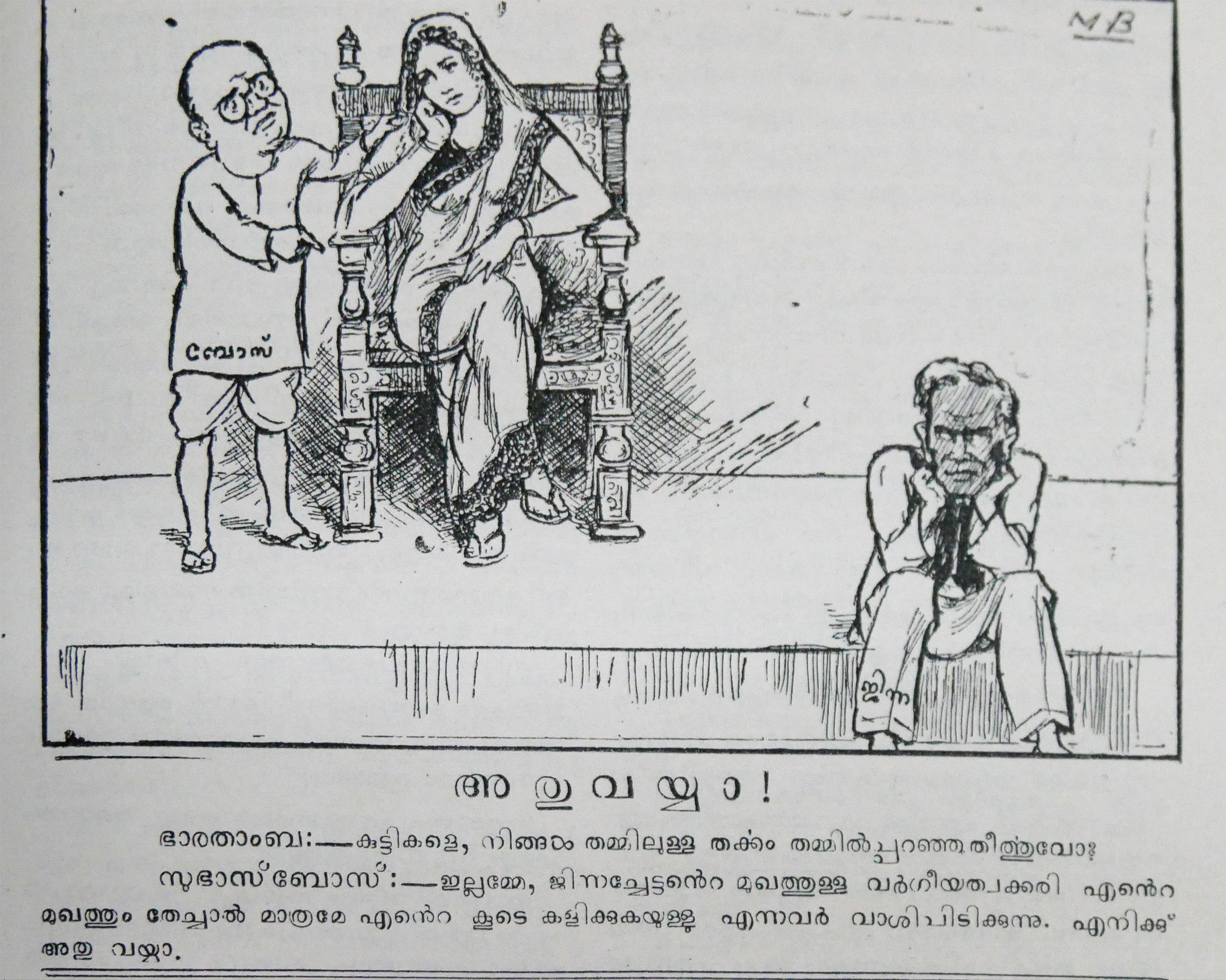

Bharat Mata

Bharat Mata was and remains a significant figure of nationalist iconography in both press and literature. She was represented as the mother goddess venerated by the nationalist leaders, who were often represented as the children of Bharat Mata, fighting for her freedom and honour. The wholehearted veneration of Mother India and associating spiritual qualities with women went hand in hand with criticism of women, a usual literary and pictorial practice of the time.

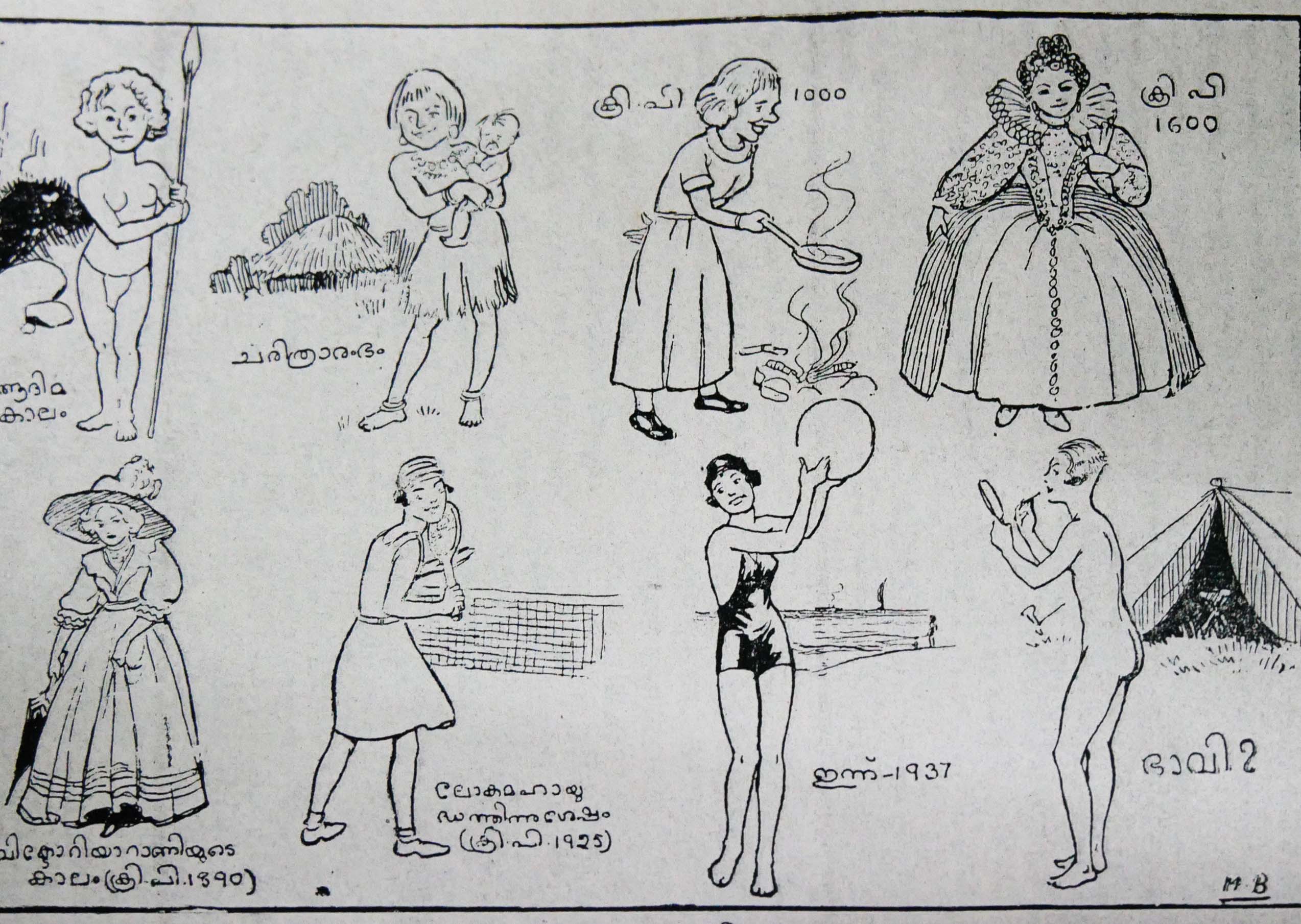

The Changing Woman

Sanjayan attacked the “modern” and “educated” women, who had become uncouth due to their education. According to critics like him, educated women acquired such traits due to their exposure to the ‘so-called modern education’ and the influences of Western culture. In his essay titled “Women Don’t Have Freedom’, he sees the movement as a hoax and claims that men are suffering from the scrutiny of their boss and their wives and are unable to form an opinion of their own. He uses the example of mythological female characters, like Sita and Kaikeyi, to prove his point that there is no gain to patriarchal society from the women’s liberation movement.

Complacent Silences

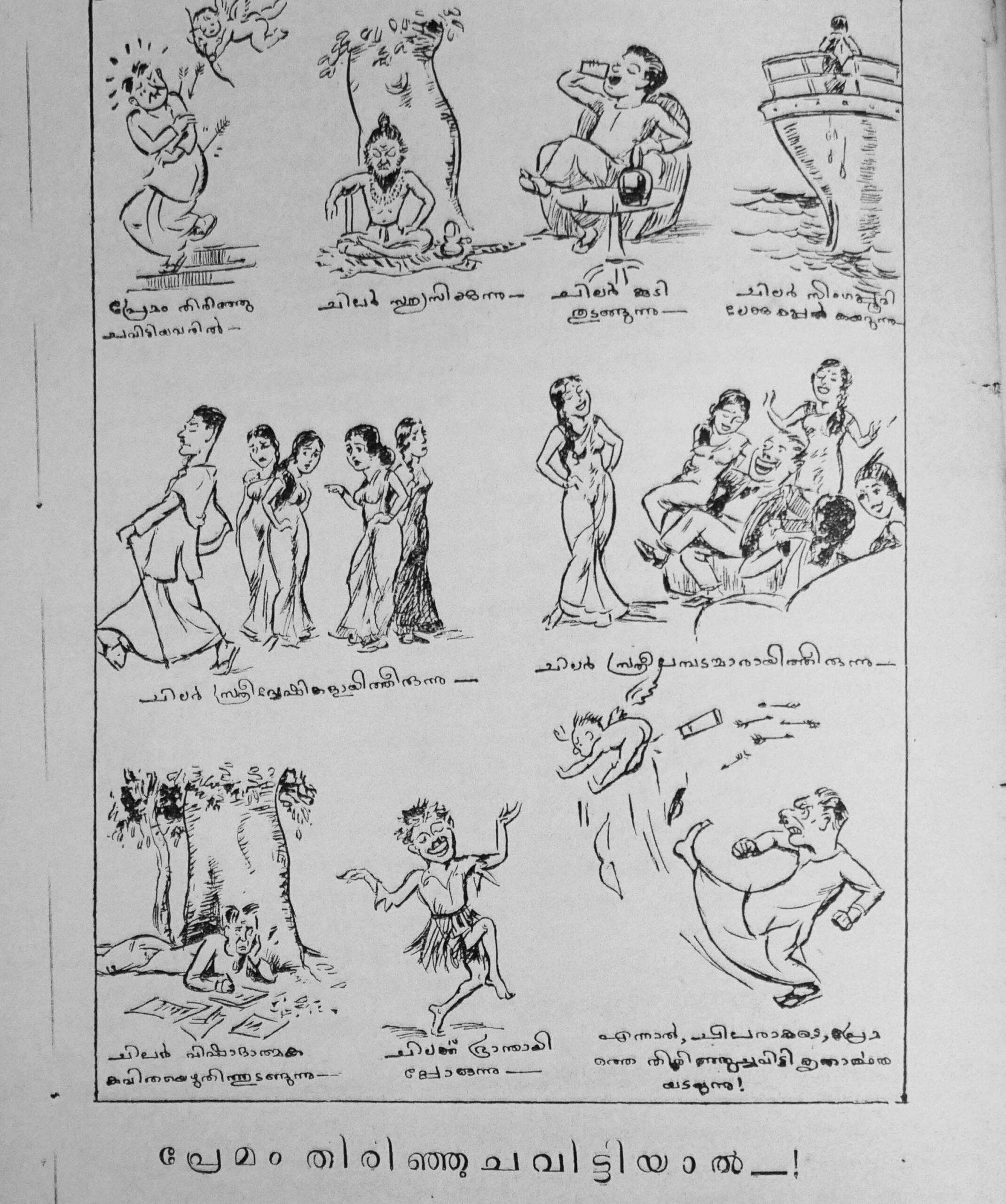

The non-conformity of women, as a trend already existing in society, is underwritten in many of his cartoons. “When love strikes” depicts men as victims, without a thought about the person on the other side. This dangerous predisposition of theirs is made worse in the modern era, and does not bode well for the kind of society he would like to see continue.

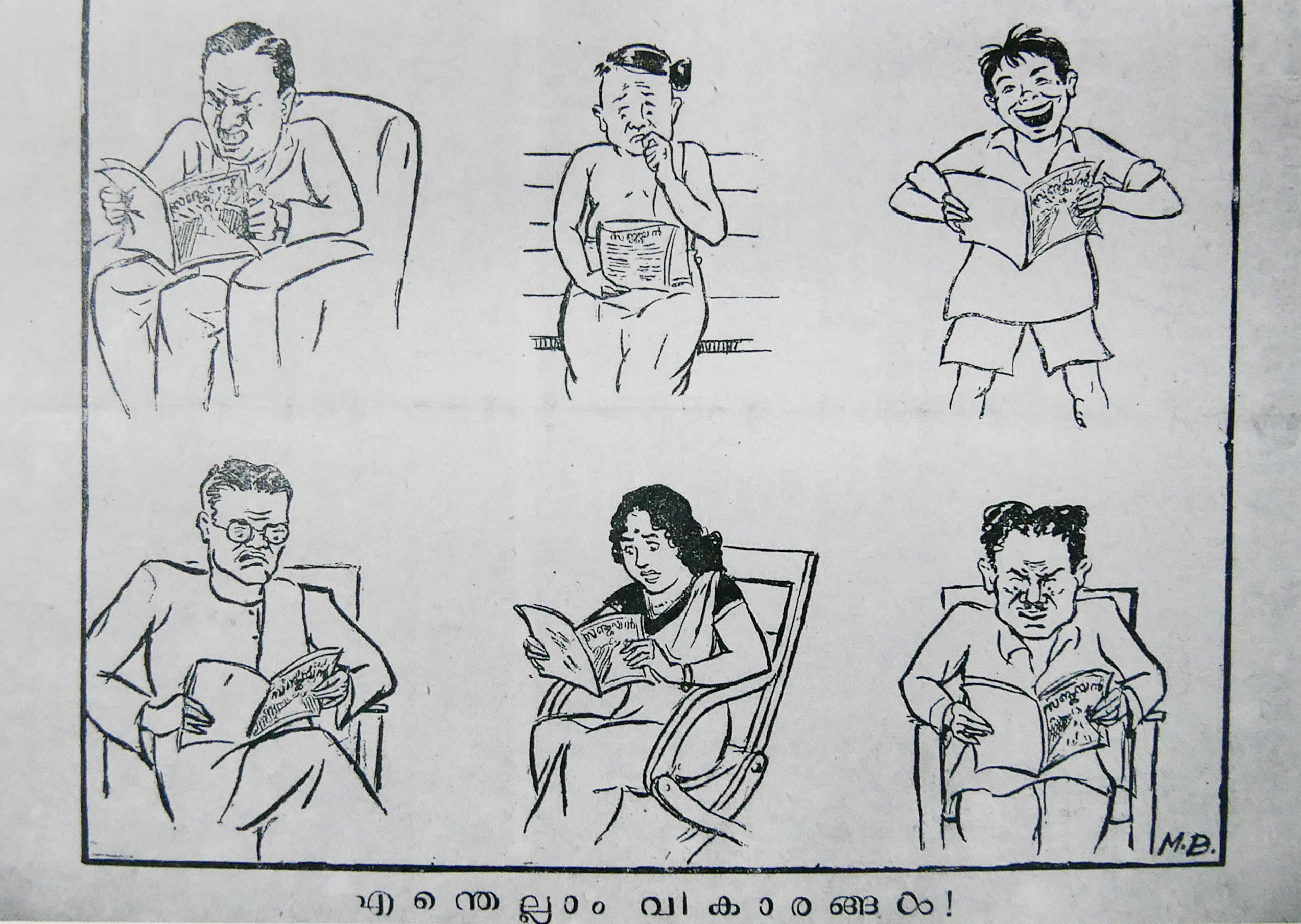

Reflecting on contemporaneous socio-political changes, he drew attention to the small yet significant changes happening in society. These cartoons can be seen as an attempt by Sanjayan to reflect and connect with his readers. He believed that the silence of the reading public towards the changing social mores made them complacent figures in social change, and played a significant role in the proliferation of these ideas.

Conclusion

As one of the pioneers of satire in early 20th-century Kerala, Sanjayan’s humour connected and polarised society when everything was in transition due to the turbulent political situation. Sanjayan’s coverage of the turmoil caused by the world wars was unique and his reinterpretation of the Punch style of cartooning opened the audience to a different world of satire. While his ideals seem flawed and do not stand the test of time, it is also important to note that his views also depict the kind of humour that was present among middle-class men of Kerala who were adapting to the changing social reality of Kerala.