Cartoons in Malayalam Magazines

Satire is an expression of discontent, a form of protest against the state of life. It is a way of fighting oppression using humour and entertainment while drawing examples from everyday life on the streets and the corridors of power. Political cartoons that mock multiple aspects of the use and abuse of power are offensive and sarcastic as their practitioners relish aiming their pens and brushes at the politically dominant.

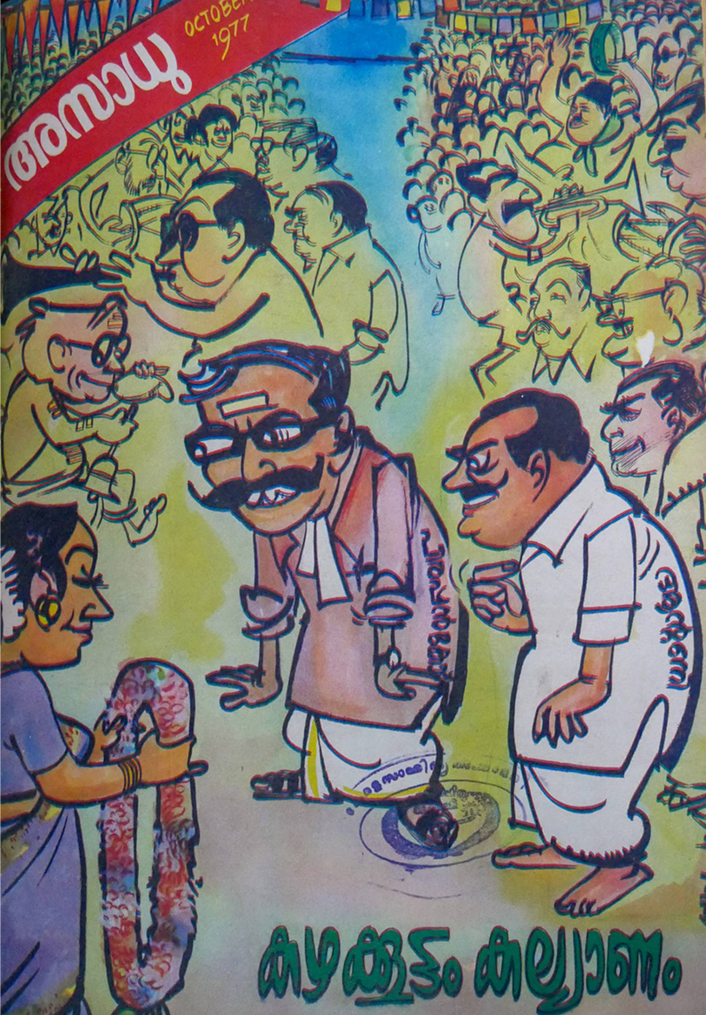

A major factor behind the popularity of cartooning was the volatile, binary, and combustive nature of politics in Kerala. This guaranteed Malayali cartoonists a perpetual source of ideas—factionalism, party hopping, double-dealing, and never-ending scandals. Their inspiration was not limited to politics in the state and the country; the functioning of various institutions including education and employment and their observations about the social life in Kerala also became fodder for cartoonists. They took the opportunity to mock and satirise the hypocritical attitude of the common folk, especially the behaviour of men towards women.

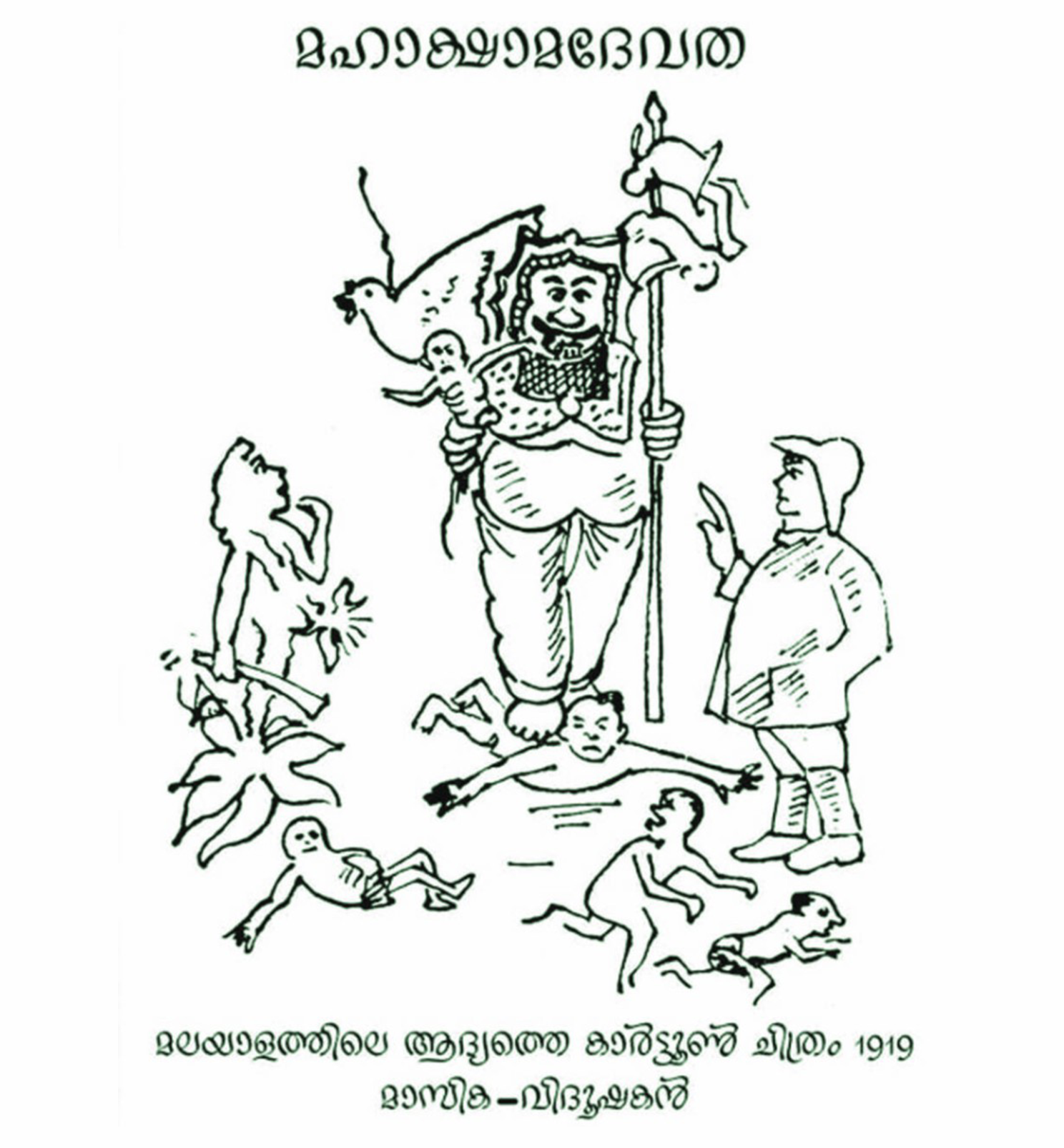

The Beginnings

The first cartoon to be published was called Kshamadevatha in 1919 in a journal named Vidooshakan. Published in the aftermath of the World War I, “Mahakshamadevatha” (or The Great Famine Goddess) depicts famine as a demon killing people while a few others are shown as running away from the demon in fright. Amidst all this is a uniformed British officer, in a hat and boots, standing to one side. A tapioca plant is depicted in an anthropomorphic form, carrying a vakathi (scythe) suggesting alternative foods (like tubers) could save desperate people from the spectre of famine.

Rising Popularity

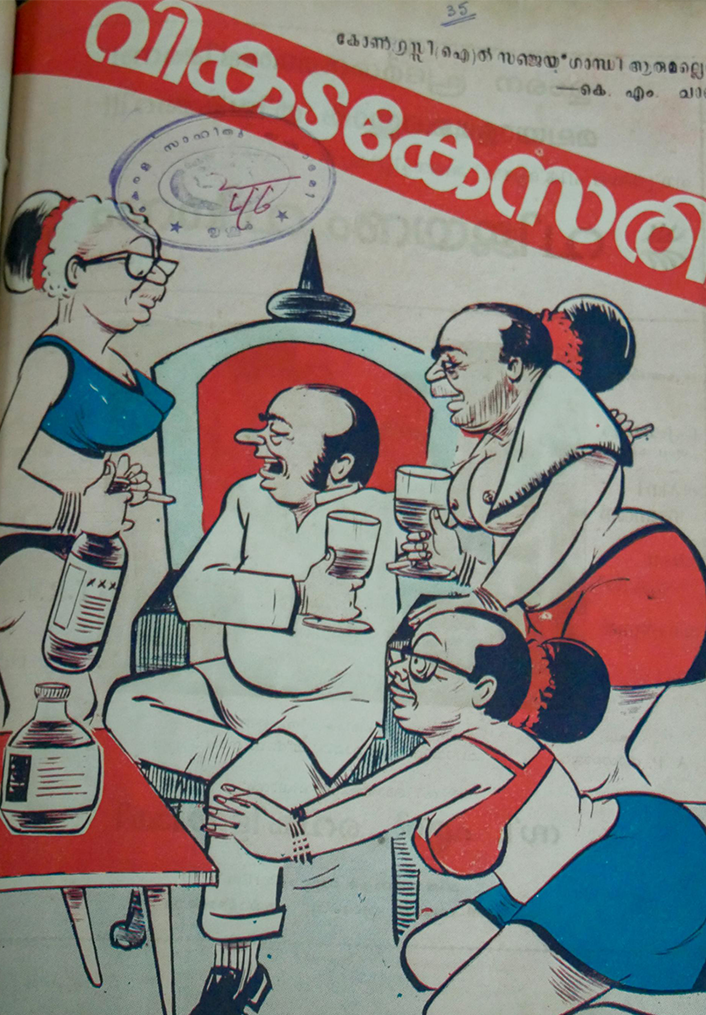

The innate Malayali tendency to pull down pompousness was further developed by cartoonists. The 1930s and ’40s saw an explosion of satirical magazines in Kerala, such as Sarasan, Vikadakesari, Narmada, and Naradan. Between 1935 and 1942, literary critic, lecturer, and humourist, M.R. Nair, known by his pen name Sanjayan, started editing two weeklies of humour and satire in Kozhikode: Sanjayan and Viswaroopam. Sanjayan relates himself with the divine spectator, ‘Sanjayan’ of the Mahabharatha, narrating the story of the war to Dhritarashtra. A supporter of Gandhi and his principles, Sanjayan’s writings and cartoons covered the freedom movement, World War II, and local politics in the Malabar province and the kingdoms of Cochin and Travancore.

Influences

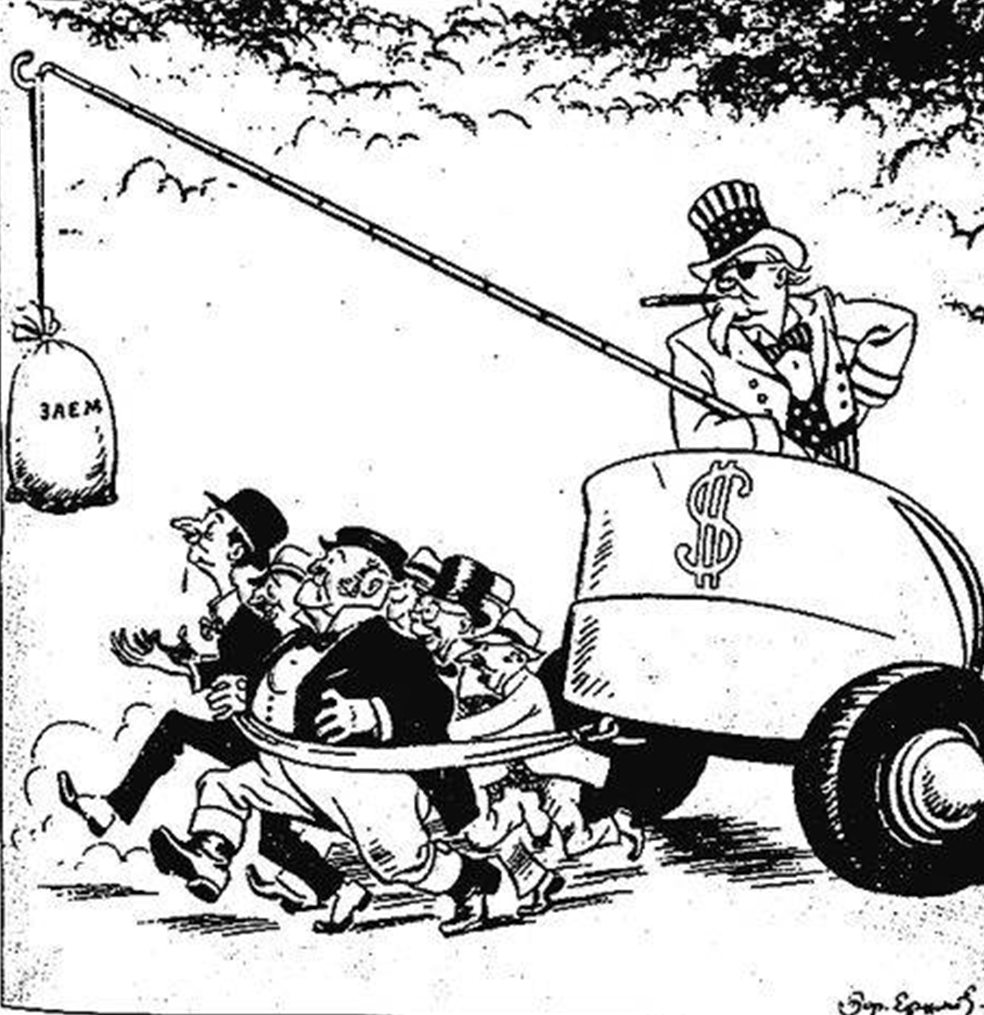

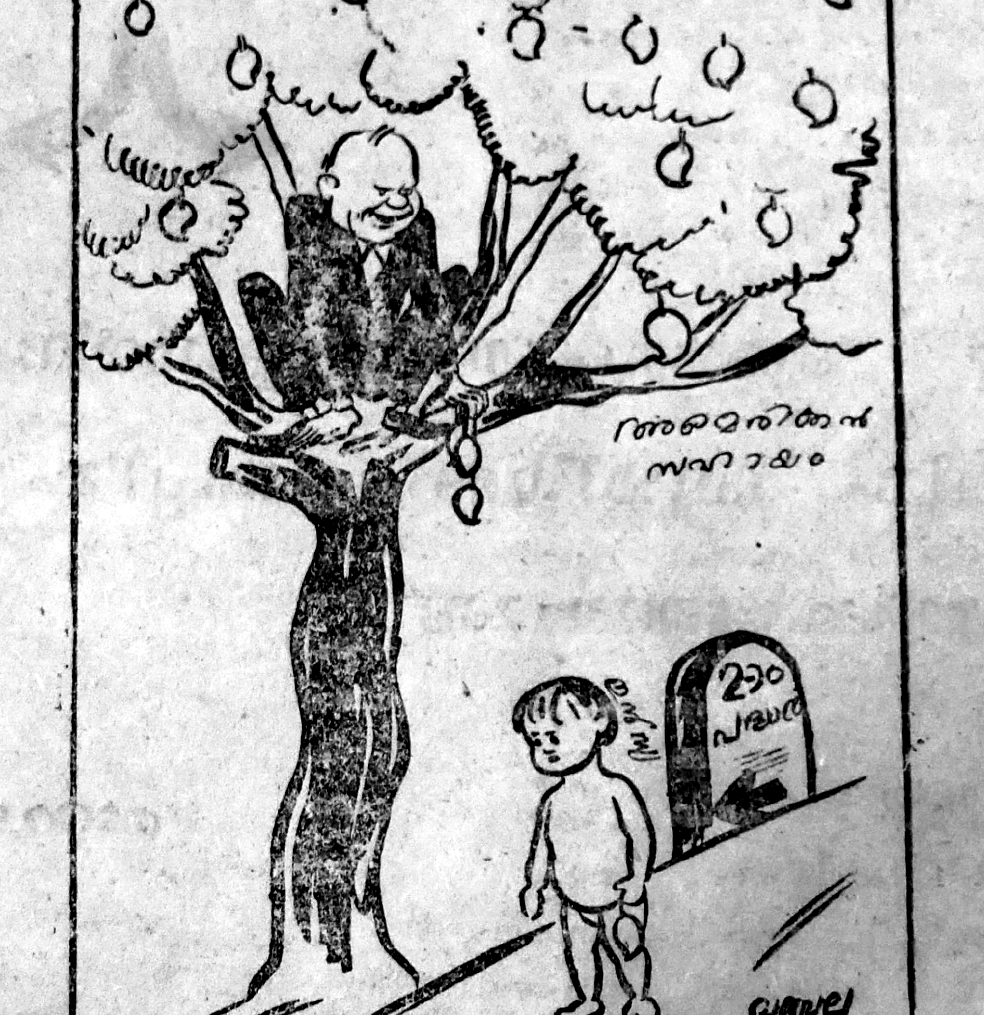

During the pre-independence era, ideas had to be represented carefully, and writers and cartoonists tread carefully, being provocative without inviting censorship, or the publication would be shut down by the colonial overlords. The imagery used by cartoonists borrowed from incidents and anecdotes from Hindy mythology, and adapted them to fit the current political events ironically. Thus, the audience could comprehend the political content in a cartoon because it represented a larger story familiar to them relating it to the prevailing situation. Other visual influences came from far and near, using symbols that highlighted the exploitation of the skewed distribution of power and wealth by powerful nations and communities. Soviet criticism of the West or Western liberal criticism of their rulers, in publications like the Punch, were influential in this regard.

Political Criticism

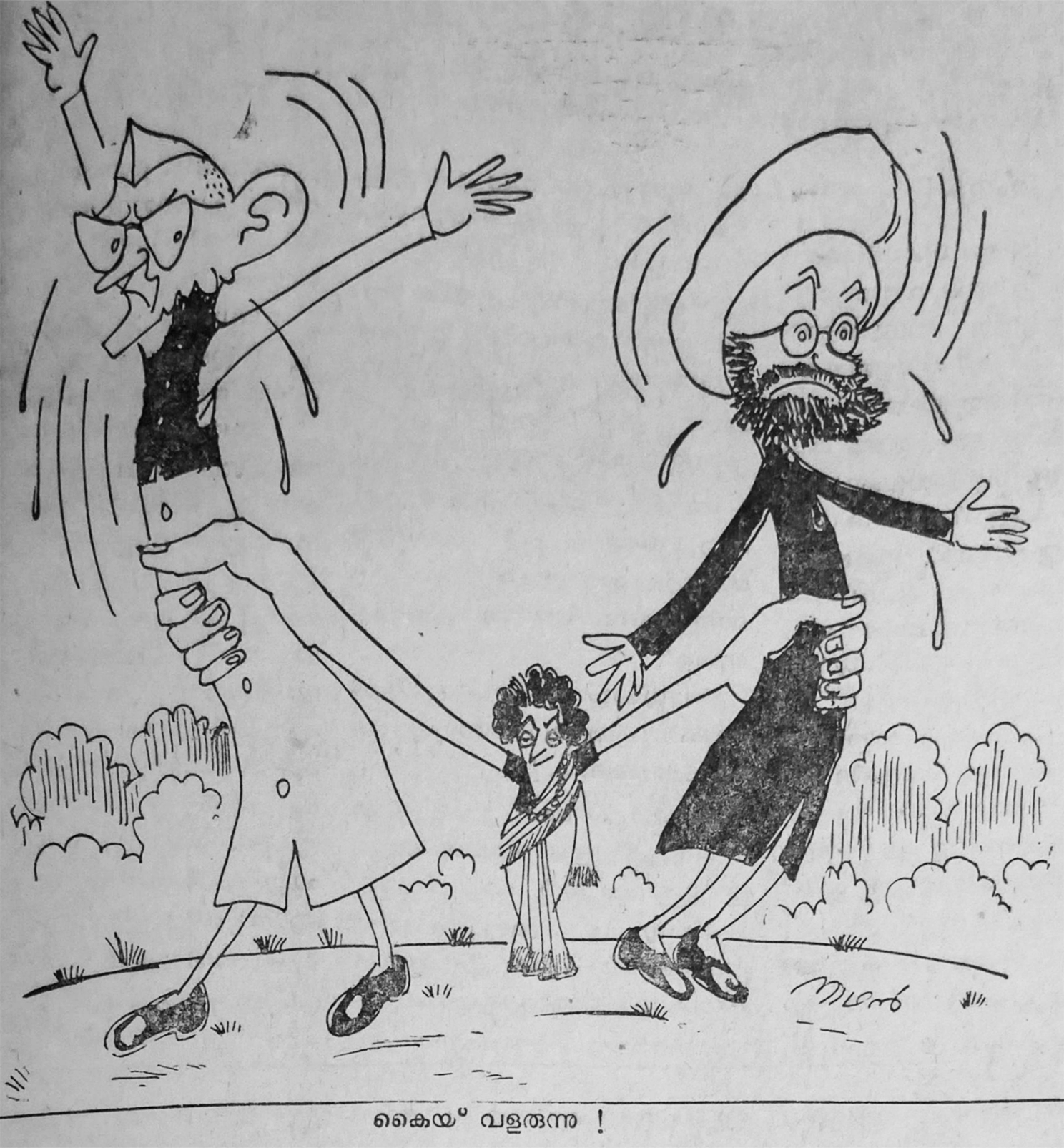

Political cartoonists in post-independence years did not carry the fear that their predecessors had under the British government and chose lewd ways to mock their targets. Cartoons ranged from harsh criticism to infantilization and emasculation of politicians. While a style of representation through animals existed, the cartoonists took the opportunity of limited censorship to exercise their full potential. In the 1960s and early ’70s, a recurring metaphor in Kerala cartoons were the double bed. The state was experimenting, as was its wont, with shifty coalition politics, which lent itself to visualising in terms of marital infidelity. These representations were not only confined to the inner pages of the magazines, it also reflected on the magazine covers which often set the theme for the issues discussed within.

Social Commentary

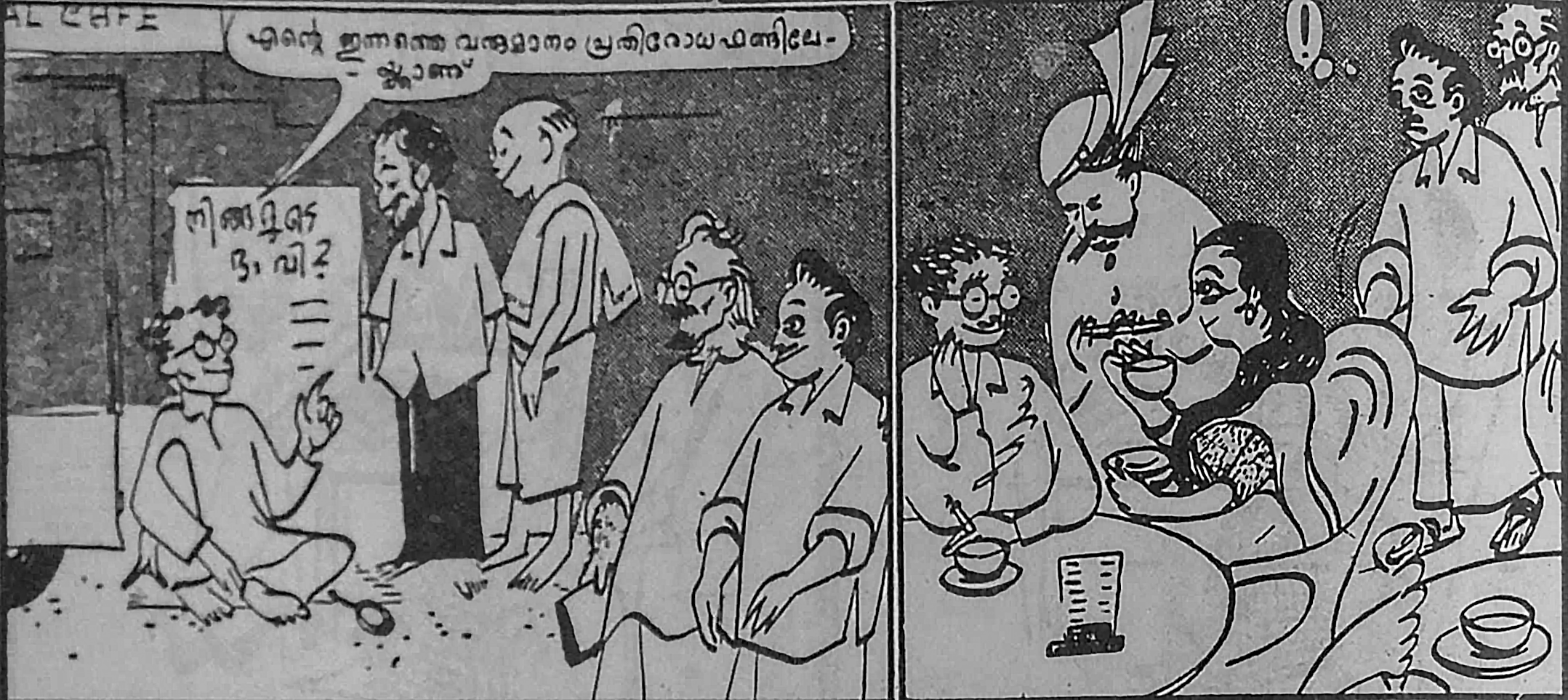

Around the same time, G. Aravindan, cartoonist and filmmaker, was pulling readers into the world of a common man observing the world around him. The weekly cartoon series, ‘Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum’ appeared in Mathrubhumi from 1961 to 1973. These episodes from the life of Ramu, an unemployed graduate, described his struggles to maintain personal relationships, his dependency on Maashu (sir), his sole mentor, and the pressures from the family of being a male child who is not yet a bread-winner. The 1960s were a period of economic crisis and unemployment, and young jobseekers like Ramu could be seen in every part of Kerala, their plight making them politically aware of the disparities and duplicities in the society of the time. Through Ramu’s eyes, Aravindan observes the changing ideologies among the youth and the intelligentsia, as they face a society on edge.

Women's World

Literacy and the consequent transformation among women were highlighted in the cartoon series through the character of Leela. Ramu’s sister, Radha, has a friend Leela, who is also Ramu’s former girlfriend. She finds a job, while Ramu is struggling between temporary jobs and unemployment. Leela and Radha are students at the beginning of the cartoon series, alongside recurring appearances of other women like Ramu’s classmate, Molly—all working women. Their lives highlight the growing social mobility of women, as they move out of Kerala, through marriages. In this way, ‘Cheriya Manushyarum Valiya Lokavum’ normalises the emergence of a class of mobile, educated, and working women in the state.

Women in Public

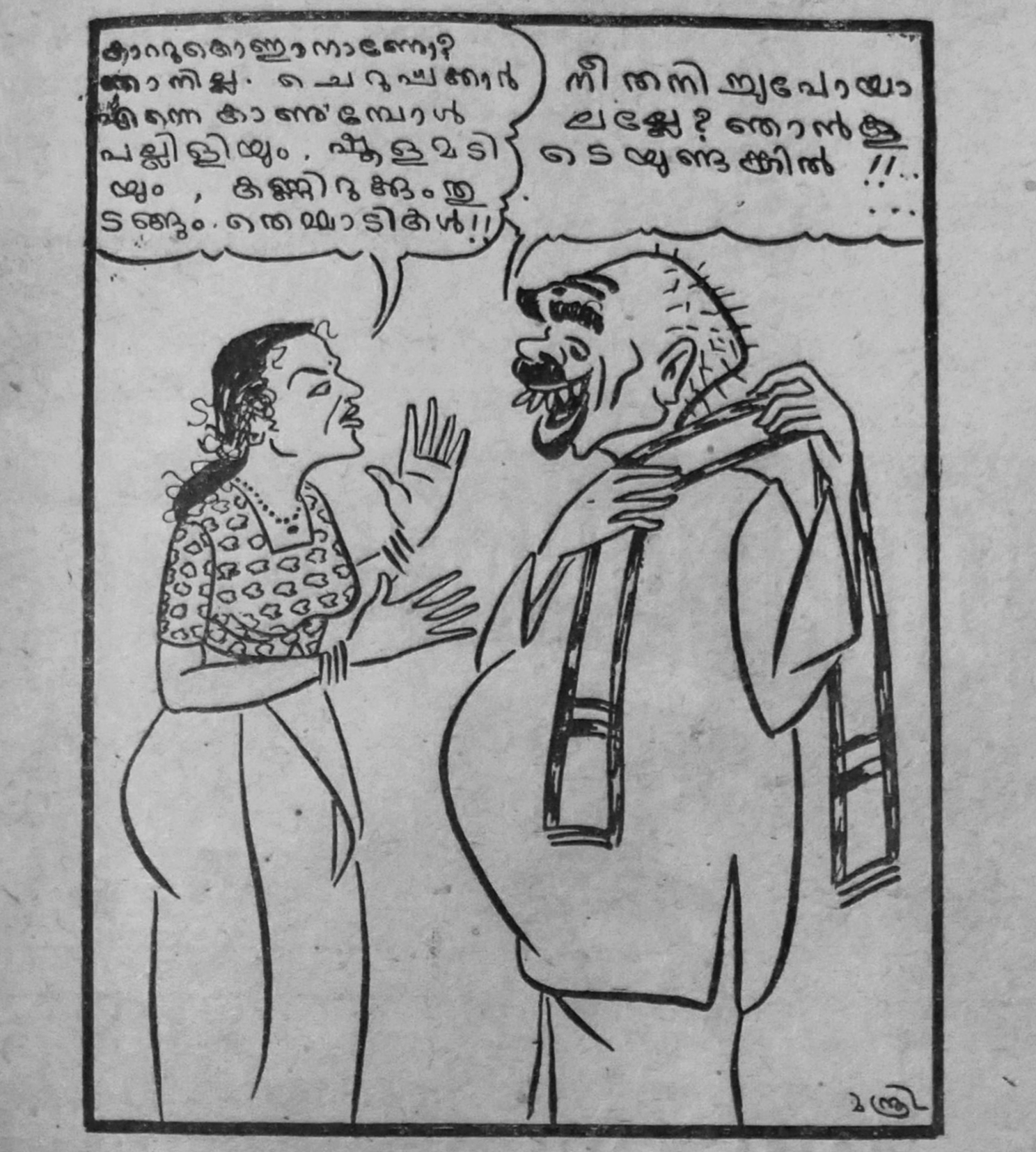

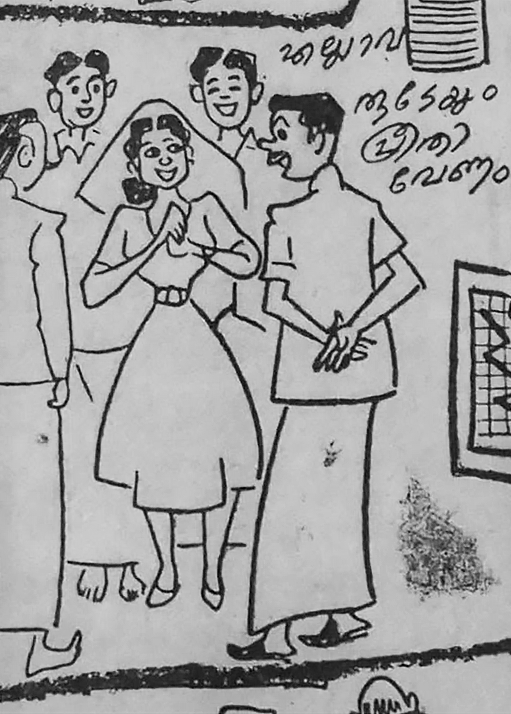

However, women were not given the same treatment in most other cartoons. The cartoon industry was dominated by men and corrupted by the ‘male gaze’, creating and perpetuating stereotypes while depicting women.

Women’s attempts to enter various institutions for education and jobs were targeted through cartoons, to the extent that they were even sexualised for occupying public spaces. Women as nurses, actresses, socialites, westernised in habits, and domineering wives and henpecked husbands were fixed characters in the language of laughter. According to these cartoons, educated women acquired certain traits due to their exposure to the so-called modern education and the influences of Western culture. Men fell victim to their advances while the women were cunning enough to cover up their intent. The Malayali male feared that the participation of women in the public space would emasculate them as a community. Women’s interest in fashion, ornaments, and accessories was a consistent theme caricatured in cartoons.

Visual storytelling is an age-old tradition of the country but giving the images a satirical twist was a colonial innovation. Visual satire entered Indian imagination and led cartoonists to wield pen and brush to voice public opinion and distrust.

In Kerala, with its longstanding history of humour, cartoons ranged from a form of public protest to tabloid gimmicks, encouraging different kinds of humour. These pictures and lines shaped the public imagination to an extent; it even became an expression of their frustration at the changing times and notions. Insecurities also reinforced conventional notions of society and the fear of change, especially among men, and since most public cartoonists were men, these reflected male anxieties and anguish regarding the empowerment of women.

Many thanks to E.P.Unni and Bonny Thomas for contributing to this article.

Exhibition Research & Content: Janal Team, Kerala Museum 2024

The exhibition is based on the Janal Article. “Bold Strokes and Comical Faces Cartoons in Malayalam Magazines.” JANAL Archives, 2024

References

Ali, Nassif Muhammed. “The Lady and the Gentleman: Changing Gender Relations and Anxieties in Early Malayalam Cartoons.” Indian Historical Review 49, no. 1 (May 30, 2022): 26–50.

Laxman. “Freedom to Cartoon, Freedom to Speak.” Daedalus, 118, no. 4 (1989): 68–91.

Sarkar, Urbee. “[VoxSpace Life] Sketching, Politics And The South: Tracing Political Cartooning In South India.” VoxSpace, January 10, 2019.

Thomas, Basil, and Gem Cherian. “Scribbling with Male Ego: Analysing the Male Gaze in the Portrayal of Women in Cartoons.” ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts 4, no. 2 (September 8, 2023).