In 1899, Winston Churchill claimed that gin and tonic saved “more Englishmen’s lives, and minds, than all the doctors in the Empire.”- Vittoria Traverso, BBC, 2020.

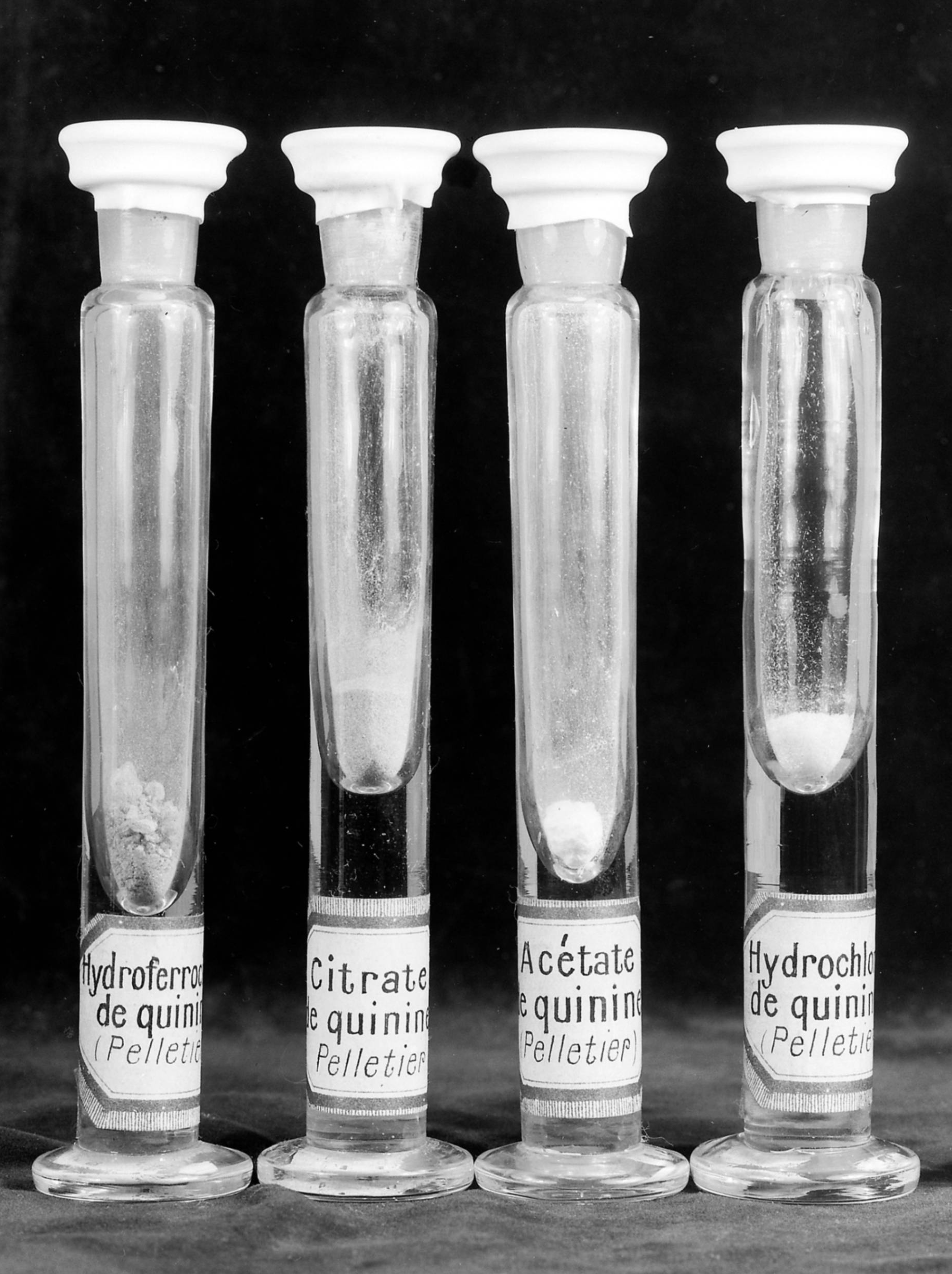

Gin and tonic had their origins, as a remedy to malaria, from the officers of Presidency armies of the East India Company. The bitter flavouring of tonic water comes from an alkaloid called quinine, extracted from the Andean fever tree (Cinchona spp.). Purified quinine replaced the bark as the standard treatment for malaria. Originally, quinine powder was added to water and drank as a remedy, but its bitterness soon led to adding sparkling water and sugar, or it was mixed with wine, gin, rum, or locally available spirits such as arrack. The tonic of that time would contain approximately 100 times more quantity of quinine than the tonic that you currently drink. So if the tonic is bitter now, imagine drinking that! This miraculous drug however became a potent agent in the colonising process of European powers.

The thin, 15 m-tall Cinchona Officinalis tree is native to the Andean foothills in South America, and is today the national tree of Peru and Ecuador. It is currently believed that malaria was not present in the Americas before European colonisation and was introduced by seafaring Europeans. By the time Europeans reached the Andes, the indigenous population already used the bark of the cinchona tree to treat other fevers and malaria, the disease spreading faster than the European colonists traveled. The locals introduced the bark to Spanish Jesuits, who in turn crushed the cinnamon-coloured bark into a thick, bitter powder that could be digested. Cinchona’s value soared during the 19th century when malaria was one of the greatest threats faced by European troops deployed in overseas colonies. Aware of the global interest in quinine by the mid-1850s, the governments of Peru and Bolivia banned the export of cinchona.

Worried at the South American monopoly over the quinine trade, British colonial administrators and scientists put together an ambitious plan that was to result in the establishment of an enormous global network of exploration, collection, and systematisation of botanical knowledge, a centralised array of botanical gardens, and a colonial science of natural resource management. At this time, the key resources for creating plantations of quinine were located on three continents: South America had the plant, but South America was not under British control. Britain however controlled India, which geographers estimated had a climate that would be hospitable for the plant. And in London itself was a pivotal resource, the Kew Gardens. This botanical nursery and garden would serve as an incubator for the plants uprooted from their native South American soil, nursing them to a state sufficiently vigorous enough to withstand a second voyage and a subsequent transplanting in foreign soil on another continent.

The Wardian Case

Before the invention of the Wardian case, plants were shipped in open containers on the decks of ships. Many plants died because of dehydration and salt spray. The Wardian case, a wood and glass box shaped like a small, moveable greenhouse allowing light to enter, was used to transport live plants and seeds. The glass cases could be kept on deck allowing the plants to receive sunlight. They protected plants from salt water but allowed condensed moisture to reach the plants.

In use by botanists from 1847 to 1962, the Wardian box was used to move the cinchona plant in secret from Bolivia to England, and onward to India to be transplanted. In 1862, the P&O Steamship Company, which transported the plants to India from England, was instructed by the India Office to pay special attention to the safety and well-being of the four Wardian cases destined for Bombay.

Cinchona in South India

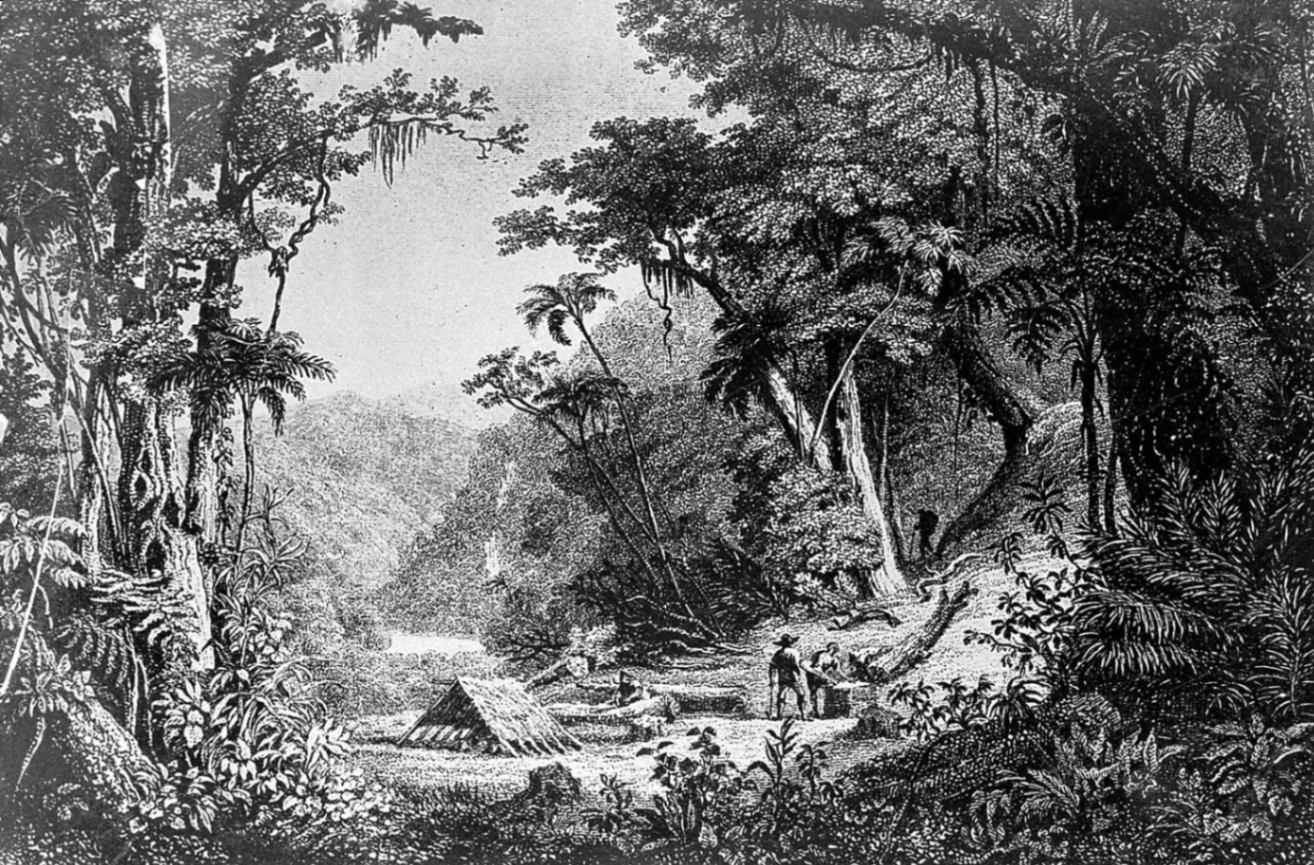

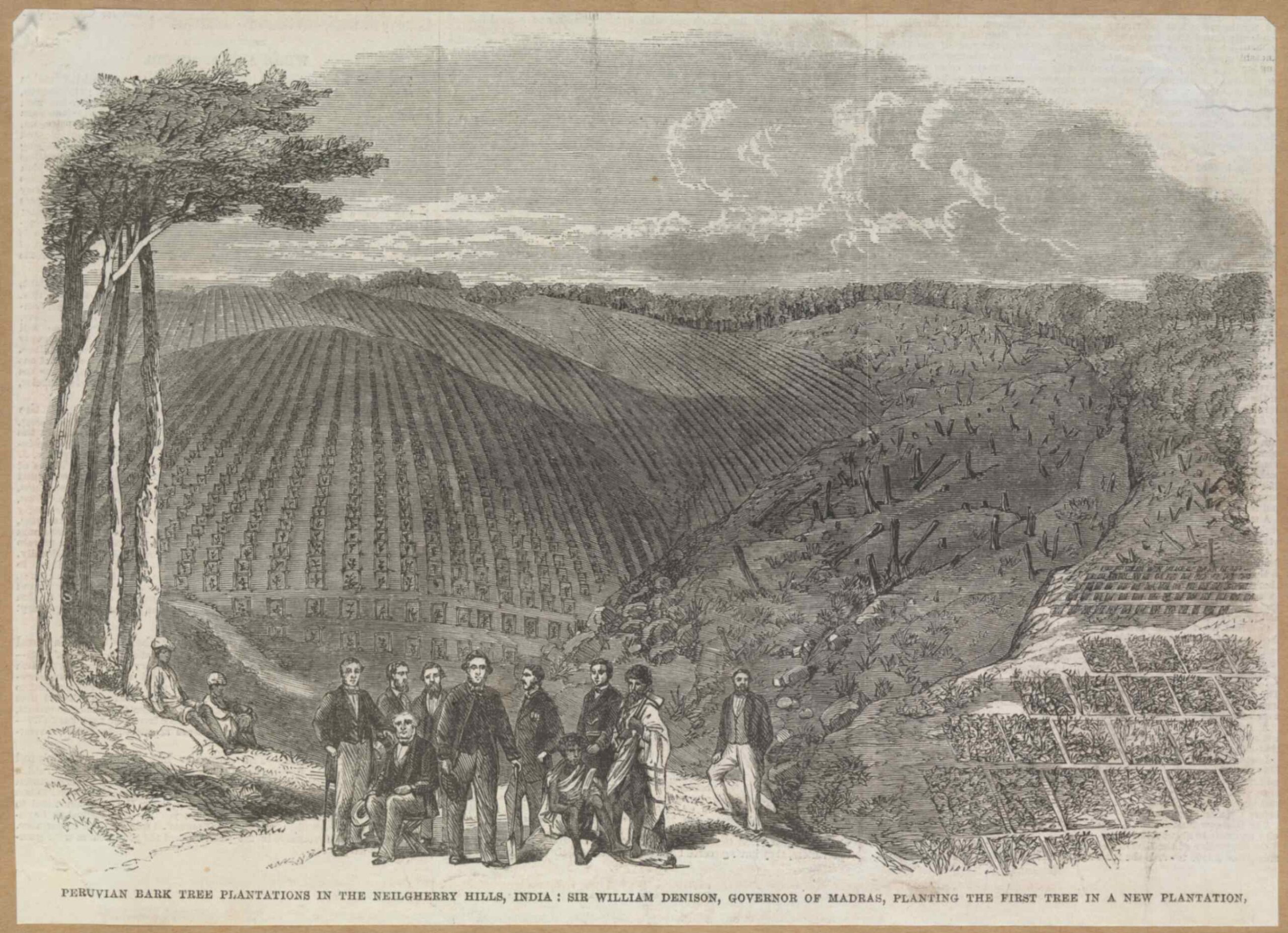

Seeds collected by both parties arrived at Kew and were sent to Calcutta for distribution to Ootacamund and Ceylon. Once at Ootacamund, W.G. McIvor, Superintendent of the Government Gardens, assisted in establishing the first plants. From 2973 plants in the Nilgiris on 9 July 1861, the total rapidly rose to 1,17,706 on 31 December 1862, supplanting the local flora, which was razed and burned to make way for the cinchona trees. In 1866, the colonial administration could survey acres of cinchona plantations where there had previously been dense jungle.

Timeline of Major Developments in the Nilgiri Cinchona Experiment

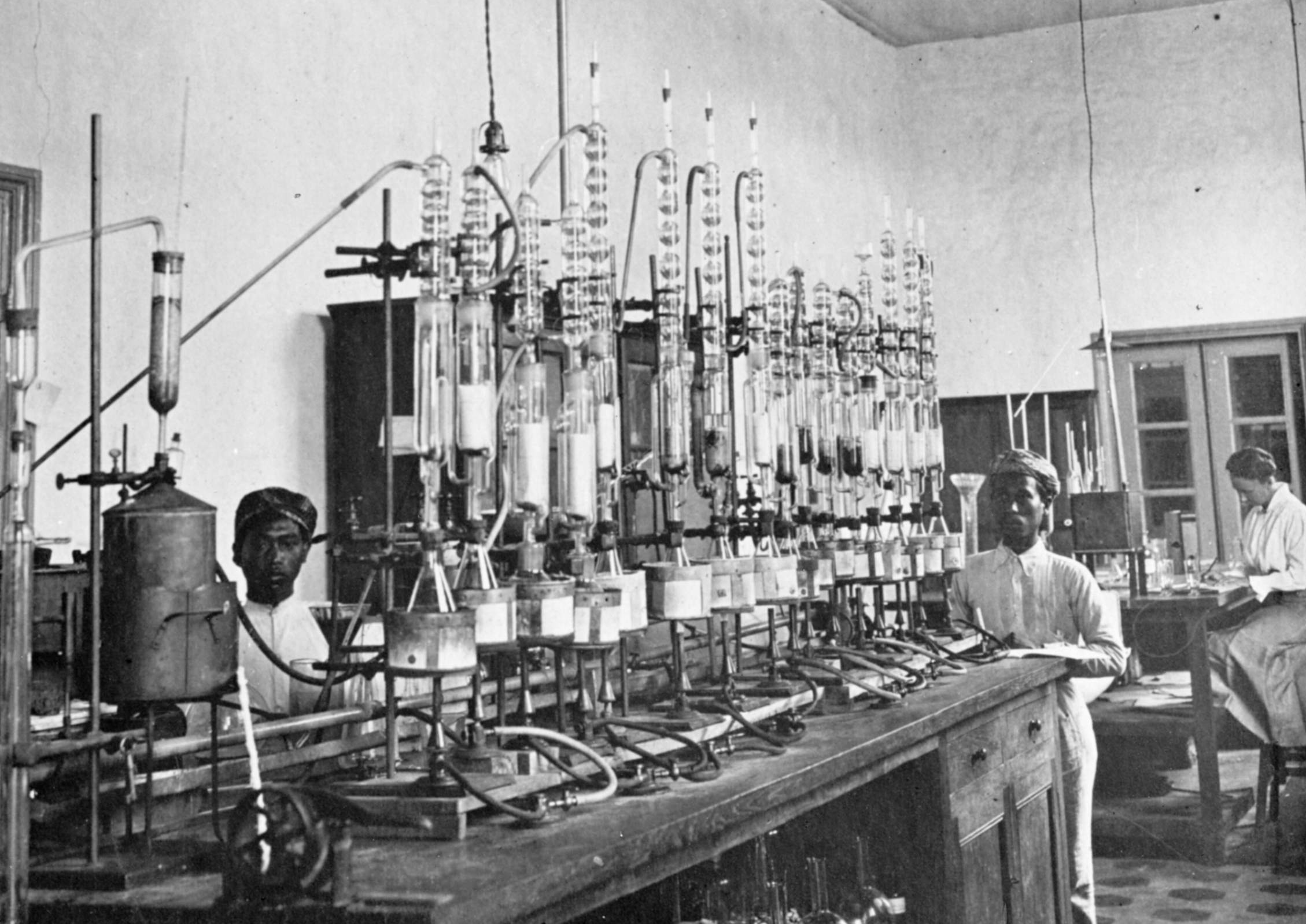

Harvesting Cinchona

In preparing a site for cinchona plantation, the forest was felled during the cold season—from November to March—and the debris was burned in March. The extremely light seed, one ounce giving some 20,000 plants, was usually sown in March. The soil for the nursery beds was sheltered by a watertight sloping roof of thatch, and the plants were carefully watered with a fine spray.Seedlings were twice transplanted, first when the seed leaves were just fully expanded. Next was at the age of three to four months, in May or June, in specially prepared "tullies" or pits when the seedlings were two or three inches high. Before planting out, seedlings would have been in the nursery for at least six months. The usual method of harvesting the bark was the coppice system; the tree was cut down close to the ground in about its 15th year, and the bark was sliced off and dried in the sun or by artificial heat.

Planting Cinchona in Kerala

Realising cinchona’s popular demand and monetary value, the Travancore Government opened a plantation in Peermade, Idukki in 1862 and later another in Munnar in 1878. In Malabar, Wayanad became a major center of cinchona production in Kerala. The first cinchonas were planted in Cherambadi, Wayanad, in 1868 and another plantation was also located at Thariyotu near Mananthavady. In 1870, the Malabar Collector reported that cinchona had grown abundantly in Wayanad and large plantations in the vicinity of Mananthavady would be a great boon to the surrounding coffee plantations in Wayanad and Coorg. Thus, Nilgiris and Wayanad became two major centers of cinchona production.Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, many trials of the hybridisation of cinchona occurred to produce trees that were both high in alkaloids and suited to the environments of India, with mixed success.

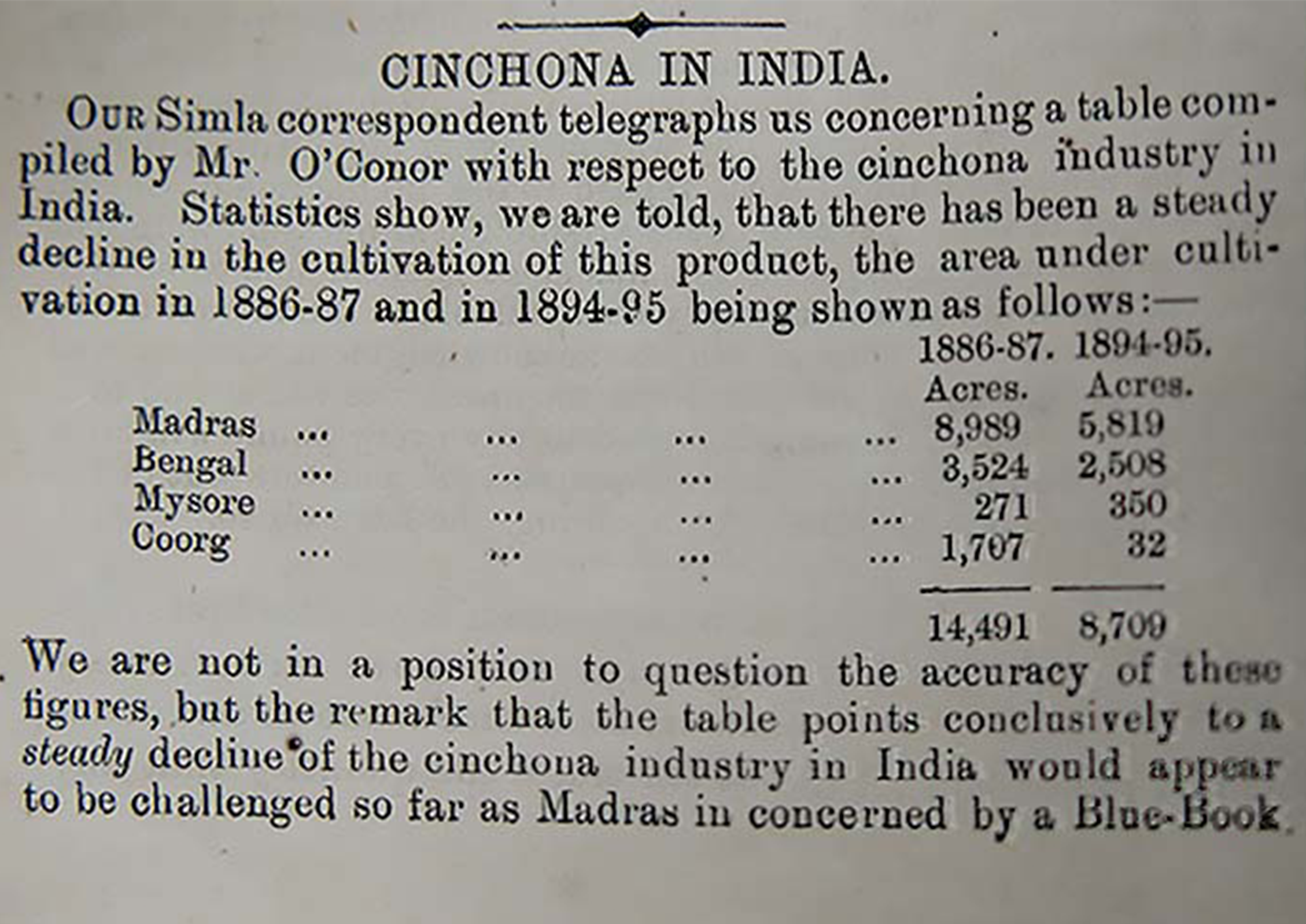

Decline in Trade of Indian Cinchona

The overproduction of cinchona from Sri Lanka and Java greatly reduced the item’s price in the international market and overtook the Nilgiri bark in terms of quantity and, subsequently, quality. Dutch plantations eventually dominated trade and the Dutch colony of Indonesia controlled 97% of the world supply by 1917. Indian cinchona was restricted to military and governmental use, reducing its value as a commodity.

German pharmaceutical chemists were commissioned to find a synthetic alternative and by 1932 had produced mepacrine, extensively used as an antimalarial agent during World War II. Substitutes developed in British colonies, and production dwindled post-war with the subsequent shutdown of cinchona plantations by the 1980s.

Despite its disappearance, the cinchona trade legitimised the influence of the imperial botanical expert in colonial agriculture and made Kew Gardens a powerful hub in the network of colonial botanical gardens holding an emerging monopoly over biodiversity heritage by the late 19th century.

Conserving Cinchona in the Wild

The centuries-long demand for cinchona ‘the fever tree’ bark has left a visible scar on its native habitat. Despite synthetic substitutes, the Andean cinchona forests of South America were over-harvested for bark as demand exploded in World War II.

Biologists tracing the genetic history of cinchona have found that the removal of quinine-rich species from the Andes has changed the genetic structure of cinchona plants, reducing their ability to evolve and change. In 1805, explorers documented 25,000 cinchona trees in the Ecuadorian Andes; which is now a part of the Podocarpus National Park, with just 29 trees.

Even though, the drugs are now developed in labs instead of being extracted from forests, plant diversity remains under-explored by science. Endangering biodiversity closes not just access to material, but also shuts down local knowledge of its use. Protecting the “pharmacy of the world” and its local pharmacists remains crucial if science needs to discover new ‘fever trees’ in the future.