The main reason we are forced to make a livelihood from kakka (clams) is because there are so few fish left to meet our daily needs, and are not enough to sustain a living from fishing for Karimeen and other varieties anymore.” - Ratheesh, Muhamma village, 2023.

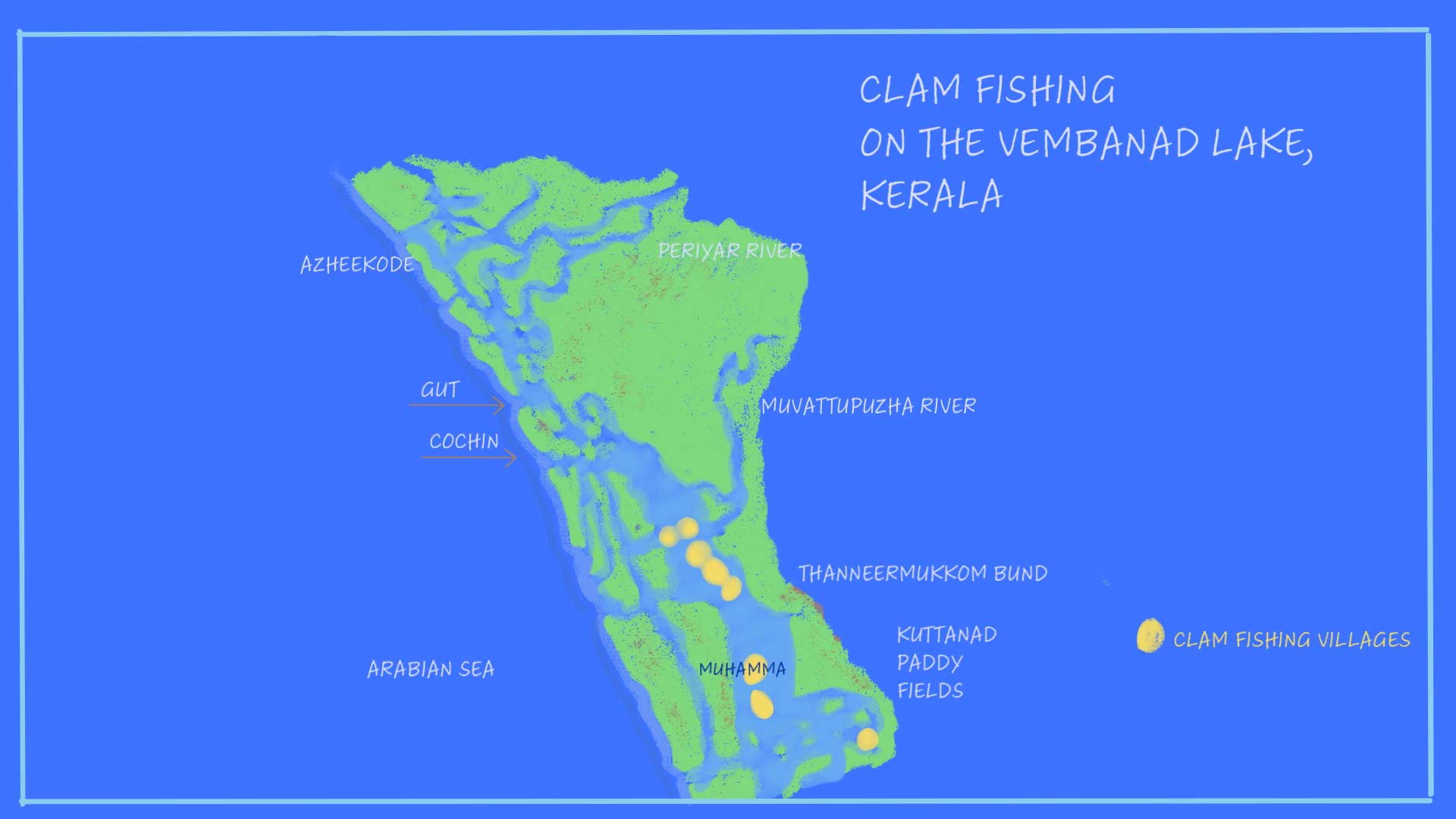

The Vembanad Lake is a large shallow lake, the second largest Ramsar wetland site in India after the Sundarbans. For centuries, the fisher-folk and clam collectors have been living off the rich biodiversity of the Lake, fishing, farming, and collecting in sustainable ways. While farming on reclaimed land began a century and half ago, backwaters tourism around the lake is more recent, albeit with higher economic impact. Rotating between agriculture and aquaculture, the people of this transitional ecotone between sea and land, have lived in harmony with the seasonal mixing of fresh and saline water.

The annual monsoon carries silt and clay from six major rivers into the Vembanad, burying clams in the southern part of the lake. Over centuries, this has created large deposits of clamshell and these neutralise acidic soil in paddy fields and fish farms on the lake.

Now, in 2024, on the brink of losing its status as a Ramsar site, this exhibition looks at the historical changes in the lake ecosystem through the lens of the clam collector’s livelihood. While black clams are native to the Vembanad Lake, fishing for clams in fishermen’s households was a minor, niche activity until less than a decade ago. As farming became mechanised, and coir production shrunk, unemployed workers from these industries began working as clam collectors. More than 90% of the clams collected from Vembanad Lake are black clams (Villorita cyprinoides), mainly used to manufacture cement, calcium carbide, and sand lime bricks.

At the lake, we set out early in the morning at 6 am; some men go out later, and we usually return between 11 am and 12 pm." - Ratheesh, Village Muhamma, 2023

The teeth along the long edge of the metal frame of the rake are 7.5 cm (3 in) long. The 70 teeth are spaced far enough for silt and debris to go through while trapping the bottom-dwelling clam from the lake floor. The nylon mesh netting collecting the clams has holes 1.5 cm (0.5 in) wide; the pole is 5 m (16 ft) long.

Divers have observed that a rake obtains nearly all the clams in a lake floor trench and that new generations settle in the raked trenches. Silt and sediment are washed off the harvest by shaking the net with a rope and raising the clam onto a boat.

Every day at Muhamma village, numerous clam collectors row their vanjis (small boats), across the lake’s width, fishing for black clams. The working day begins before dawn and continues till 4 pm most days.

Sometimes we have to travel around 8 or 9 kilometres to fish for clams, there are lesser clams near Muhamma. To correct this, the government and a few organisations have started the process of ‘clam relaying’, where baby clams from the north of the barrage are brought here to repopulate. This is helping us.” - Ratnakaran, Muhamma village, 2023

Clam Processing Activities

The clam collectors’ homes are right beside the canal leading to the Vembanad Lake. They return to berth their canoe at the landing quays by the afternoon. These stone-lined quays are about 2 m (6–8 ft) wide and have steps so that a person can, if necessary, stand in knee-to-thigh-deep water. Upon arrival, they rinse the clams again to wash out any remaining mud, and carry them in baskets or a wagon to the processing site in their yards.

The meat is put into plastic bags and returned to the fishermen’s respective homes for sale to prospective buyers. The fishermen and their families also consume this meat.

The clam shells are heaped and stored aside to be sold later to buyers from cement factories. Due to the high calcium content in their shells clams are classified as a mineral resource and regulated by the Mines and Minerals Act 1957. The collectors pay a membership fee to Clam collection Societies and a royalty to the government for a harvesting license.

About ten years ago, I could collect enough clams in just 2–3 hours. Now I work the whole day to procure it," - Ashokan, clam collector, Muhamma village, 2023

The Deteriorating Quality of Clams

As many as 5,000 local people still earn their livelihood collecting clams in the Vembanad wetland area, spread over 36,500 hectares and fed by six large rivers and seawater. However, the quality of clams has been affected over the last decade. Clam collectors believe that chemicals from reclaimed farmlands, illegally discharged effluents from tourism houseboats, and lakeside industries such as coconut husk retting have contributed to pollution and affected marine life in the lake.

The reasons for the disappearance of fish in the lake have changed over the years but it all started with the Thaneermukkom Barrage. The barrage was built to help the paddy farmers in Kuttanad, but it has affected us in the process because the barrage stands in the way of the migratory route of various fish. So, the fish count drastically went down. Later in 1993 there was a release of pollutants into the lake which killed the remaining fish in the water. However, with time they slowly began to repopulate." - Mr. Poovu, ATREE Co-ordinator, Muhamma, 2023

But most recently, during COVID-19, many people had nothing to do all day. So, everyone began going to the lake to fish to pass the time, leading to overfishing, leaving the lake barren with no fish to catch and sell in the market. Once again, the fish count is reduced, and we must rely on clam fishing as our main occupation.” - Ratheesh, Village Muhamma, 2023.

Preventing entry of seawater, the Barrage reduces the salinity in the southern part of the lake to below 10 ppt (parts per million). Since clams need more than 10 ppt of salinity to breed, there is a big possibility of clam deposit vanishing from this end.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many people back to their homes in the village, increasing the number of fisher people dependent on this for livelihood.

To revive the clam deposit along Vembanad Lake, a relaying project was launched near Thanneermukkom Barrage. Proposed by Ashoka Trust for Ecology and Environment (ATREE), the Bengaluru-based research group, the project was approved by the Fisheries Department in 2016. ATREE coordinator T.D. Jojo explained the key intervention it proposes: clam is to be collected from the northern side of Thanneermukkom Barrage and deposited in protected areas south of the Barrage.