Are they in character? We talked a lot, eight hours ago; and now, it is as if they don’t know us at all. So, till when does this transformation last? ... Vinayak, a viewer, Baavod, 2023.

Theyyam, an ritual art form from Northern Kerala, is closely intertwined with the land and its people’s history, customs, and beliefs. Tracing the existence of 300 to 400 theyyams, academicians believe the diversity emerges from the local nature of the lore behind many of the characters. As a performing art form exclusive to Kannur and Kasargode districts, I had never seen a Theyyam performance, except for short videos of performances in films and on YouTube channels.

On discovering that a community of Theyyam performers was the setting for a Malayalam film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello, I started enquiring about the schedule of performances. Learning that a three-day Theyyam Mahotsavam was being organised by the family of an old acquaintance, I decided to attend the function at the Baavod Varayil Marappura, Kannur.

A week later, as the sun beat down on the lush landscape, I found myself at the heart of a bustling kaavu, where the three-day Theyyam festival had already commenced. I arrived on the second day before noon, disappointed that I had missed one performance from the previous day.

Despite the heat of a sultry summer’s day in March, a small crowd had already gathered. I was greeted by my friend’s family with warm smiles and taken to the veranda of the house in the compound, where I offered my prayers. Filled with anticipation, eager to soak up the vibrant energy surrounding me, I entered the kaavu. The air was filled with excitement as performers donned their elaborate costumes and painted their faces in vibrant colours, ready to bring the stories of Gods to life.

Kaavu, People, and Performance

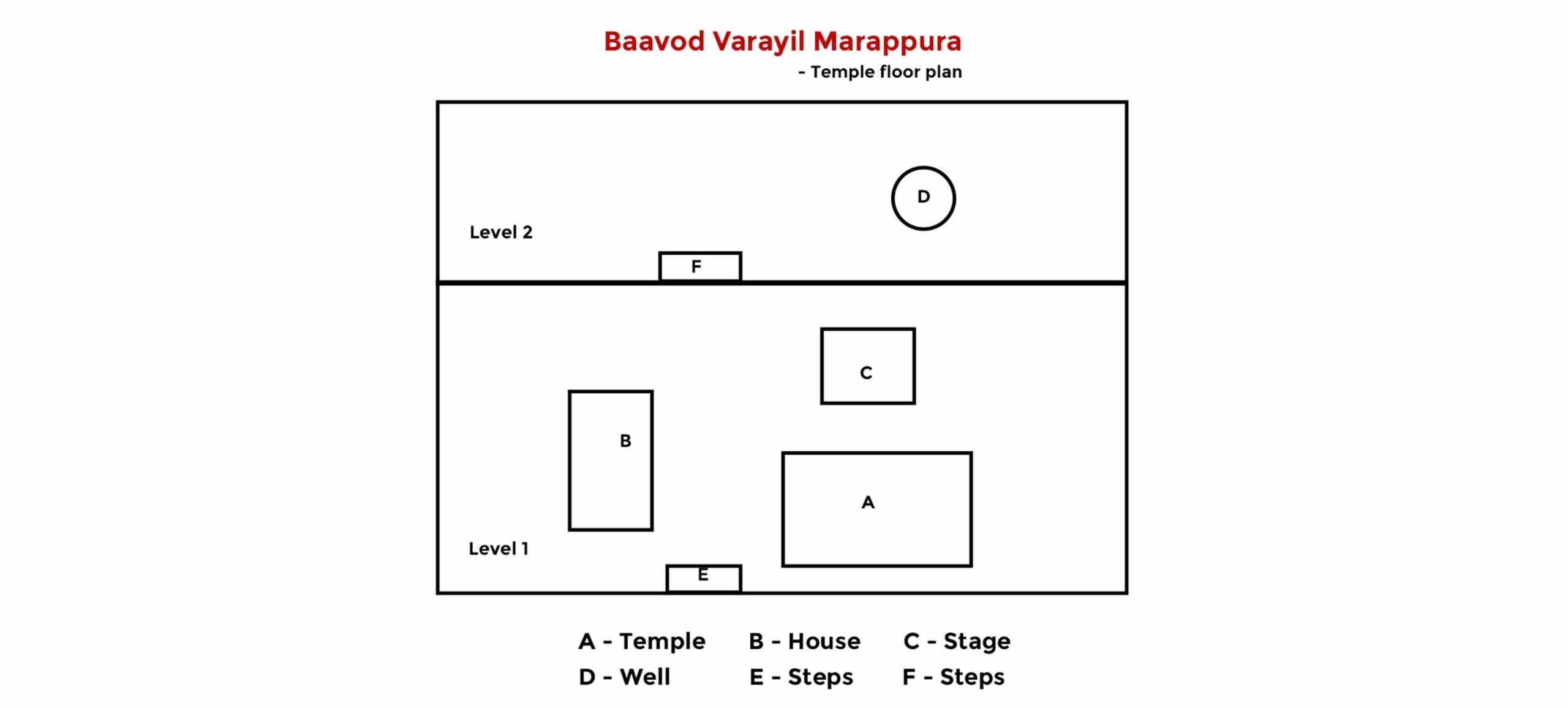

The kaavu was larger than I had imagined, featuring a traditional Kerala house, the temple, and a stage-like structure arranged in a triangular formation. The family that owned the temple and surrounding kaavu had formally registered it as a religious trust, reflecting the site’s evolving dynamics and significance. The janmaari, Phalgunan, oversees the temple along with other kaavus in the region. “I take care of everything related to this kaavu,” he said, adding that the family had raised funds to build the current temple three years ago.

The site also featured tharas (raised concrete platforms) for performing religious rituals. The festival attendees use the lower level to prepare and serve food. Though not as well-maintained as the upper level, it exuded a sense of community and shared responsibility, with the attendees taking part in cooking and washing dishes. This human aspect of the event, with conversations, hospitality, and reverence towards Theyyam, was a contrast with the cinematic portrayals of a wild, overgrown kaavu, yet offered a deeper understanding of the cultural significance of this space.

“This is not how I imagined a kaavu. This is too clean, where are the overgrown plants and snakes.” ... Overheard at the kaavu, 2023.

From Humans to Gods: Makeup in Theyyam

The transformation of performers into god-like characters is a central aspect of a Theyyam performance. My interactions with the performers before they prepared themselves introduced me to individuals with familiar lives. However, during the makeup process, I noticed the remarkable metamorphosis that has been written about by many scholars.

I observed how long periods of shutting the eyes and being still, alternating with glances at their reflection in the mirror, plays a significant role in their transformation. The solitude of the makeup process allowed performers to embody their characters, enter their fluid selves, and create a path that takes them into another realm.

For the audience, the makeup not only visually changes the performer, but also blurs the boundaries between reality and fiction. By disconnecting the real and the imagined, the Theyyam performance invites the audience to suspend their belief, connecting humans to other worlds, drawing the audience into a transformative experience.

“Lying there with their eyes closed, they have a long time to mentally prepare themselves and imbibe the character. When they get up and see themselves in the mirror, it is not themselves they see, it is the character.” ... Phalgunan, the Janmaari (overseer) of the kaavu, 2023.

Customs, Practices, Gender

There was a distinct separation in how men and women interacted in the kaavu. During the Pooja ceremony, men occupied the space at the centre of the kaavu, and women stayed within the confines of the house or the veranda. However, as the performance progressed, the performer moved to the space occupied by the women rather than asking them to come forward. This arrangement highlighted the positioning of men as direct participants while women were physically detached from the central space.

As I stood waiting after the performance for a chance to talk to the Muthappan Theyyam, I didn’t know what exactly I was waiting for. I had met the performer earlier, when he had agreed to speak to me about his experiences after the performance. Would he have any recollection of speaking with me earlier in the day?

The festival’s strict guidelines dictate the selection of the main Muthappan performer, emphasising the importance of preserving historical and cultural integrity. “Someone from that family has to perform”, Chandran, a member of the family, told me while explaining that a descendant of the original Muthappan performer who performed at this kaavu has to be present for every festival.

When my turn came to speak with Muthappan, he calmly took my hand and spoke a few reassuring words. Standing in front of him, I forgot about my interest in interviewing him. I forgot the performer and only saw the character.

“Baavod kaavu is known for its Muthappan theyyam, and at least one performer who becomes the muthappan theyyam has to be from the family that began the tradition.” ... Chandran, a member of the family, 2023.

Learning Through Practice

I did not follow the thottampaattu, the lyrical content of the Theyyam, a mix of an archaic form of Malayalam and another dialect that I could not recognise. As the musicians seemed perfectly in sync, I asked one of the nadaswaram players who looked well into his seventies, how they learnt the language of Theyyam.

I was told they started out young, observing Theyyam for years before becoming part of a performance. Their keen observation and knowledge of the thottampattu enables them to keep up with the Theyyam.

The performers and instrumental players exhibit remarkable coordination, even during performances of longer duration. Their learning encompasses the characters and makeup, their backstories, costumes, and other rituals associated with the performance.

“Since I have been seeing these performances since childhood, I can understand the lyrics. Outsiders won’t be able to understand the thottampattu.” ... Rajan, a member of the family organising the festival, 2023.

The Duality of Theyyam

In Theyyam, we see the operation of a collective memory in which the questioning of abuses within the caste hierarchy is made possible by the divinity of the performer. Each performance reiterates the circumstances of the abuse, and those present are invited to invest it with a meaning derived from the cultural baggage they carry.

The performer receives honour and respect while in Theyyam form because of the character that everyone sees him to be. The fact that everyone, irrespective of caste and social standing, bows down to the Theyyam is sardonic, given that the performer, who usually belongs to a lower caste, has to take permission to become the Theyyam from an upper caste patron.

Theyattam assumes an audience in the know, itself producers of meaning. The curt text of the thottam expects the audience to grasp its double meanings. There is a proverb in Malayalam, which says of persons who show false humility, that they are like a performing Malayan (performing caste).

Theyyam Audience

Theyyam rituals involve blessings, interactions with the audience, and the serving of prasadam. The prasadam offered during the festival, comprising boiled red beans, coconut pieces, and dry fish, is different from traditional temple offerings.

There are two distinct audience groups. For the locals, having grown up with the ritual, the performance appeared routine, and they did not pay attention to every single thing. In contrast, the YouTubers and other outsiders showed curiosity and fascination that perceives Theyyam as novel and exotic. The fact that Theyyam is geographically bound to the northern region of Kerala attracts non-locals interested in understanding the customs and rituals associated with such events.

As I stood with the Theyyam, who was still in character, I noticed that a young woman standing quite close to us was filming our conversation. The performer continued to talk to me calmly but then suddenly turned to the woman and asked, “Who gave you permission to do all this?” He did not sound angry, but his stern tone combined with the make up on his face, made him look intimidating. The girl, quite startled at being addressed by the Theyyam, swiftly turned off her camera and took a step back. The performer added, “You know, you can continue. But know that I am letting you do this. If I had not given my permission, if I had said no, everything on it (he pointed at the camera) would go blank. Nothing would be seen.” Saying this he turned to me and continued our conversation as if nothing had happened.

“If I did not give my permission, if I had said no, everything on it (the camera) would go blank. Nothing would be seen.” ... Karnavar vellattom performer to a Youtuber recording his conversation with me, 2023.