Unacknowledged Histories

The Beginnings

Women’s magazines were started in colonial Kerala with the express purpose of educating women. Women’s education and status were perceived as being connected to the status of the state and community, especially since there were debates in other locations about the backwardness of Indian women in general.

Magazines and periodicals, they capture the history of the present—what mattered to people, what were the raging issues of the times, and what was considered fashionable. Women’s magazines from colonial Kerala debated significant issues related to women that catalysed women’s education, health, and access to civil society in the state.

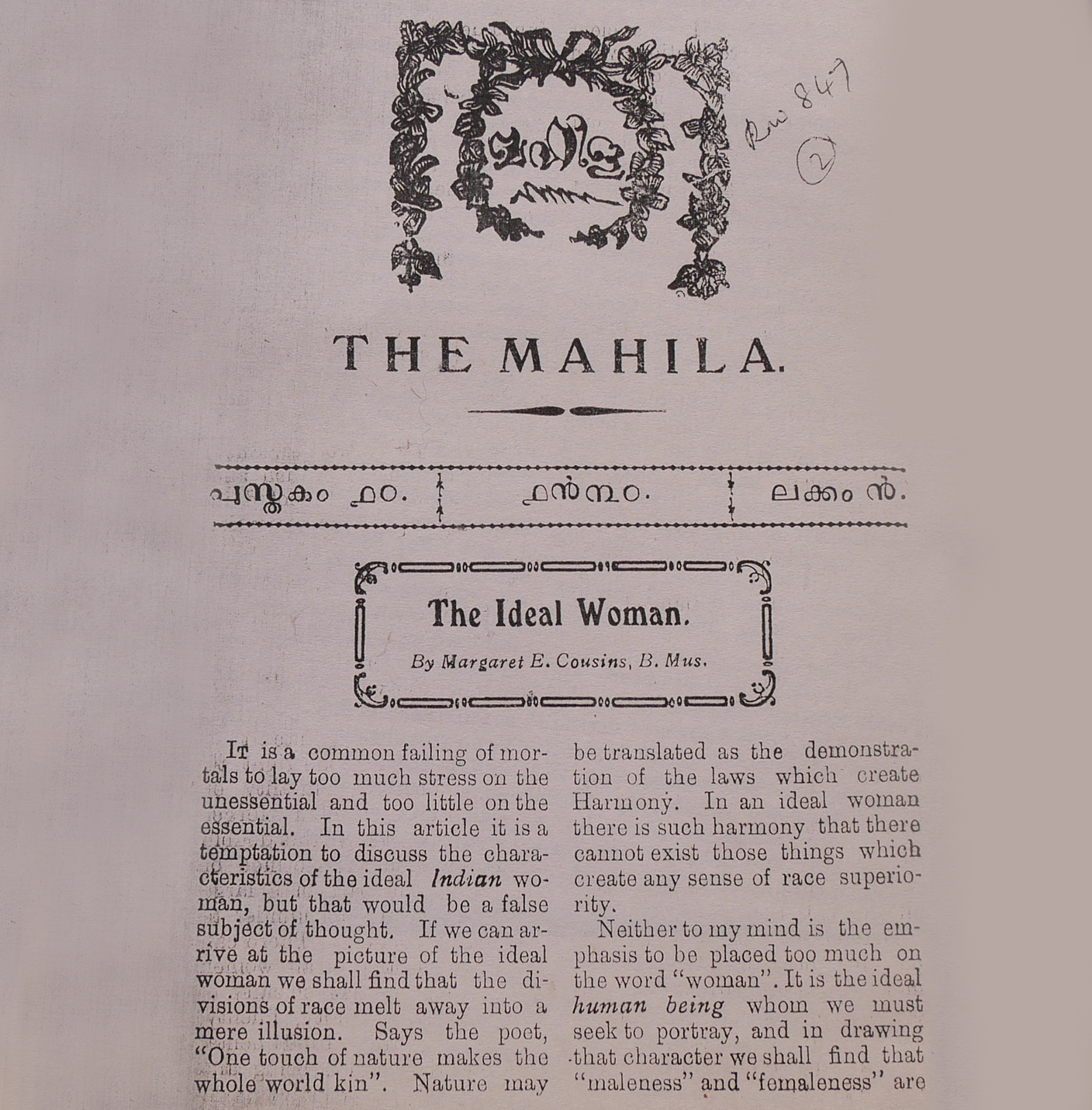

The First Magazine

The first women’s journal, Kerali Sugunabodhini, was launched in Thiruvananthapuram in 1884. The magazine ran for around six months initially.

The immediate reason was an increased interest in the subject of women’s education. Reading Malayalam in the printed form had gained popularity by this time, almost 36 years after the first newspaper and journal were printed in Malayalam. These were Rajyasamacharam and Paschimodayam, both by Herman Gundert, in 1847, while the first magazine to be published was Jnananikshepam by the CMS Press in 1848.

“No woman has written in it. Scholars like M.C. Narayanapilla were the writers. Even if there were women’s names, it would have been the pseudonym for a male writer.”

– G. Priyadarshanan, media historian on Kerali Sugunabodhini, 2023

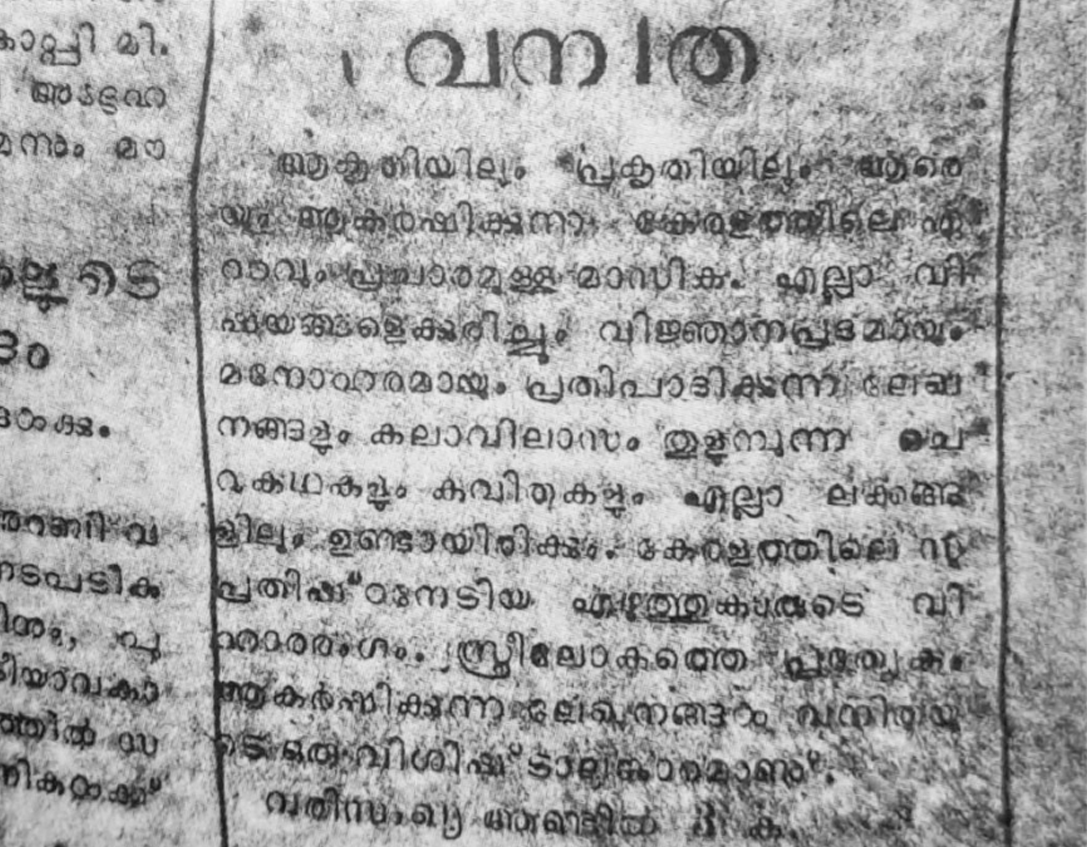

Edited by women

Sharada (1904) was the first magazine to be published for women by women from Tripunithura. Sharada was edited by three women: T.C. Kalyani Amma, T. Ammukutty Amma, and B. Kalyani Amma. It ran until 1910, with a hiatus in the middle. A few years later, in 1913, T.K. Kalyanikutty Amma launched another magazine called Sharada, from Punalur which lasted for about a decade.

Another magazine called Bharathi was published in Kozhikode in 1904. There is not much information available about this magazine.

Who were the writers?

People told me that the articles in these early magazines were probably not written by the women, but by their spouses or brothers. Can one not extend the same argument to the male writers also? It may have been written by other men.”

– Haneena P.A., researcher and curator, Kochi, 2023

Prominent novelists, critics, and poets often contributed to both women’s and general magazines in colonial Kerala. The women writers, exceeding 220, came from diverse backgrounds—government officers, school inspectors, professors, principals, doctors, lawyers, and legislators. Notable figures from this era, such as K. Chinnamma (1882-1930), B. Kalyani Amma (1884-1959), Mary Poonen Lukose (1886-1976), Muthukulam Parvathi Amma (1904-1971), Anna Chandy (1905-1996), Haleema Beevi (1918-2000), and K. Kalyanikutty Amma (1920-1996) were writers and activists, simultaneously holding various jobs.

The male contributors included renowned poets, novelists, and essayists, such as Ulloor S. Parameshwara Iyer, Kumaran Asan, Vallathol K. Narayanamenon, and E.V. Krishnapilla. Many of the male contributors to these magazines are well-known in the current era, while the women contributors have largely been forgotten.

The writers and publishers were related or knew each other. The magazines featured contributions from other parts of India, sometimes in English, and sometimes in Tamil. Both male and female writers were actively engaged in contributing to multiple magazines, held editorial positions, and played significant roles in the public domain.

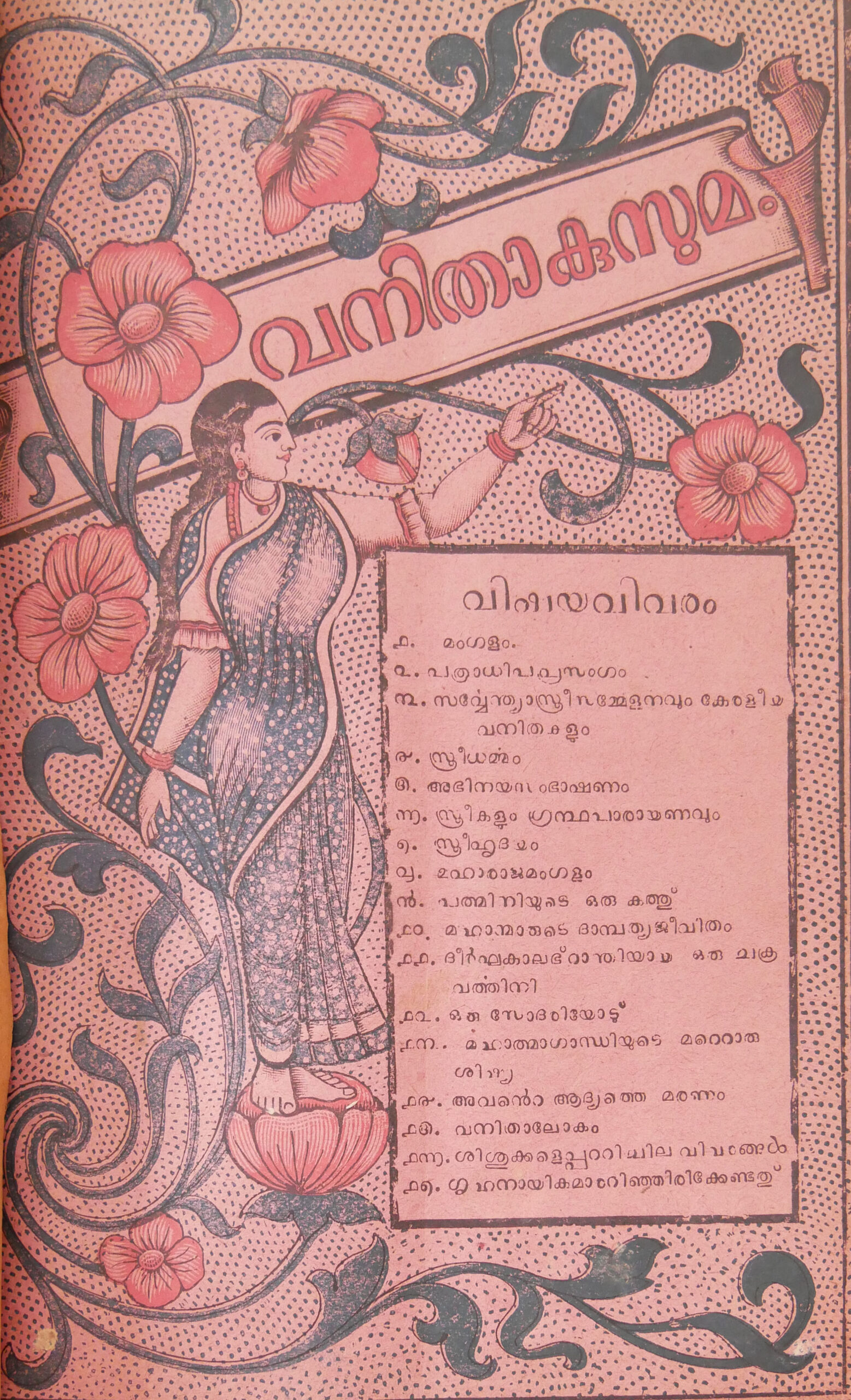

Articles published in one magazine would elicit critical responses that were published in other magazines or journals printed at the same time. Periodicals with similar or even the same name were published from different locations at various times. For instance, Vanitha was a popular name for magazines started by several people in 1944, 1959, and 1975. Some magazines carried the term Vanitha with another word, like Vanithakusumam or Adhunika Vanitha (started by Haleema Beevi). Prior to Haleema Beevi launching Bharatha Chandrika (a general magazine) in 1944, a weekly magazine with the same title was being printed in Kollam, owned by M.K. Abdulrahiman Kutty.

Education: The Most Discussed Topic in Early Malayalam Women’s Magazines

Women’s education became more common and valued in the 1920s and 1930s. Writers faced the challenge of proving that modern education was not a threat to Malayali culture or morals, but a way to improve their social status and important for the progress of the family and society.

Women entered new fields of work that were once male-dominated. Women’s lifestyles changed resulting from the social changes and a few educated women were choosing to remain single. These led to a demand for new syllabi and curricula that would reflect the changes while maintaining the traditional roles played by women within families.

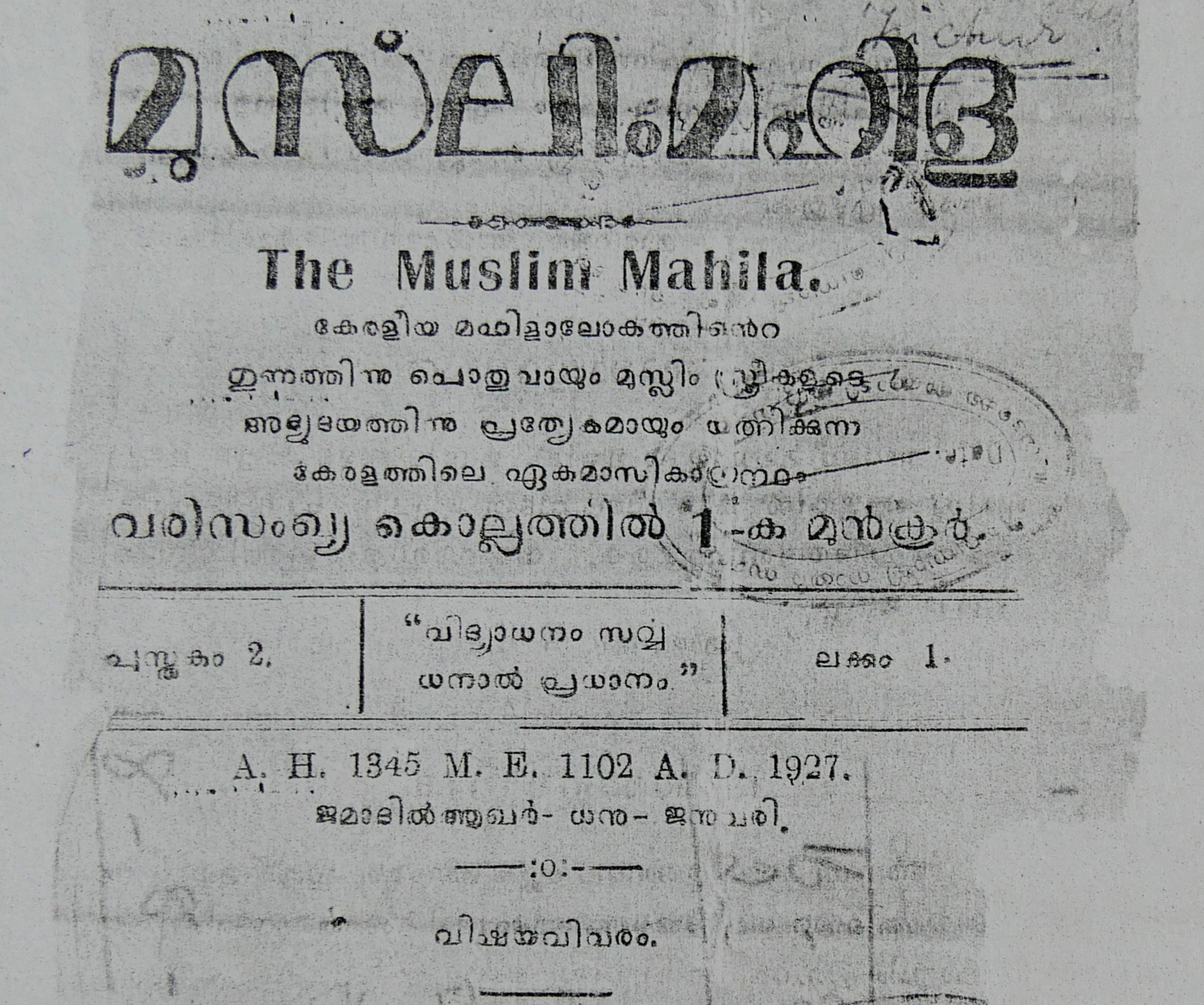

“It is clear from the various issues of Mahila (Muslim Mahila) that the magazine is trying to eradicate prejudices and inequities rooted in Keralite women’s world, especially Muslim women’s world.”

– a reader of Muslim Mahila, 1924

“Very few women have supported English education and higher education of women,” writes Prof. Sreebitha from the University of Kannur about the Ezhava women’s magazines of the period. Rather they argued for homeschooling and someone from the community teaching the girls.

Readership

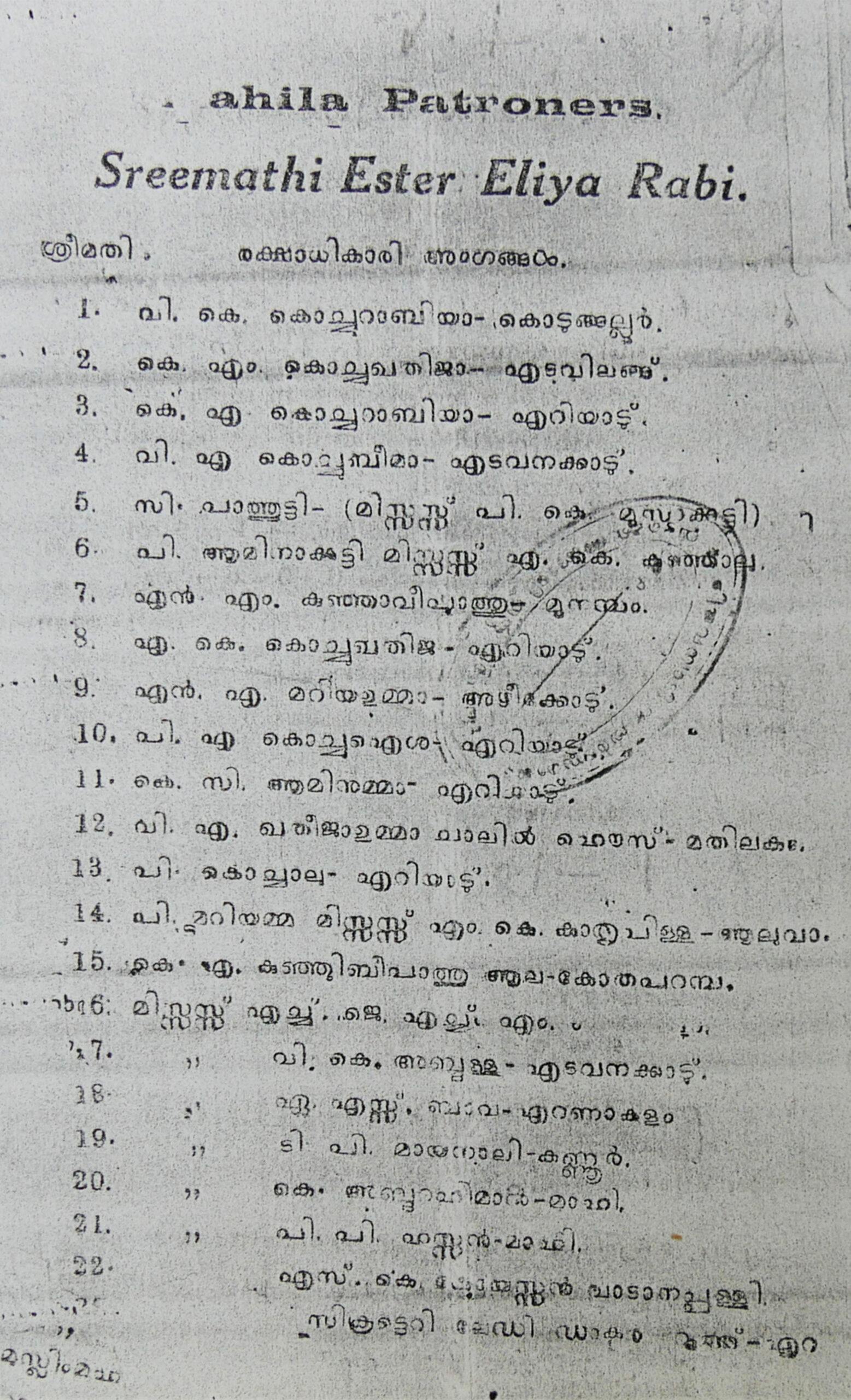

Early Malayalam periodicals targeted a specific audience, those with the means to subscribe to them at ₹1 to ₹4 (local currency) annually. They were accessible through post, educational institutions, reading rooms, or libraries.

The highest recorded subscription for a women’s magazine at the time was 2,000 for Vanithakusumam, which commenced from Kottayam in 1927. Christhava Mahilamani published from Thiruvalla followed with 1,500 subscribers, while Lakshmibai in Thrissur had 1,300 readers. Mahila, one of the longest-running women’s magazines run by women, was established in 1921 and continued for two decades. Government schools began subscribing to it in 1924, with official records indicating 500 subscribers. These numbers may seem modest by today’s standards, but they reflect the historical context of women’s readership.

“Vanithakusumam had women writers. It became a model for all the magazines that followed. It had a clear-cut aim and wanted to achieve certain things. Vanithakusumam was published in Kottayam. It was in print for two and a half years.”

– G. Priyadarsanan on Vanithakusumam, 2023

Specific Audiences

While the magazines were ostensibly for all women, some were tailored for particular communities, later expanding their reader base. They did not overtly emphasise regional or community affiliations, yet articles touched upon region/community-specific matters.

The Muslim, Christian, and Ezhava communities started several women’s magazines. Haleema Beevi started Muslim Vanitha in 1938, Vanitha in 1944 and Adhunika Vanitha in 1970 for Muslim women. The periodicals did not run for very long. Researcher and curator, Haneena P.A. spent many months trying to locate copies of the Muslim Vanitha in the Ulloor Smaraka library, Thiruvananthapuram.

“The library had been closed for 10 years. The person in charge finally opened the library for my use after three months of request. I was given just three hours in this huge library. Everything was jumbled up, the call numbers of the books before and after this were on the shelf, but this particular magazine was missing… Locating copies of these magazines is the most difficult aspect of research.”

– Haneena P.A., Kochi, 2023

Overview of Content

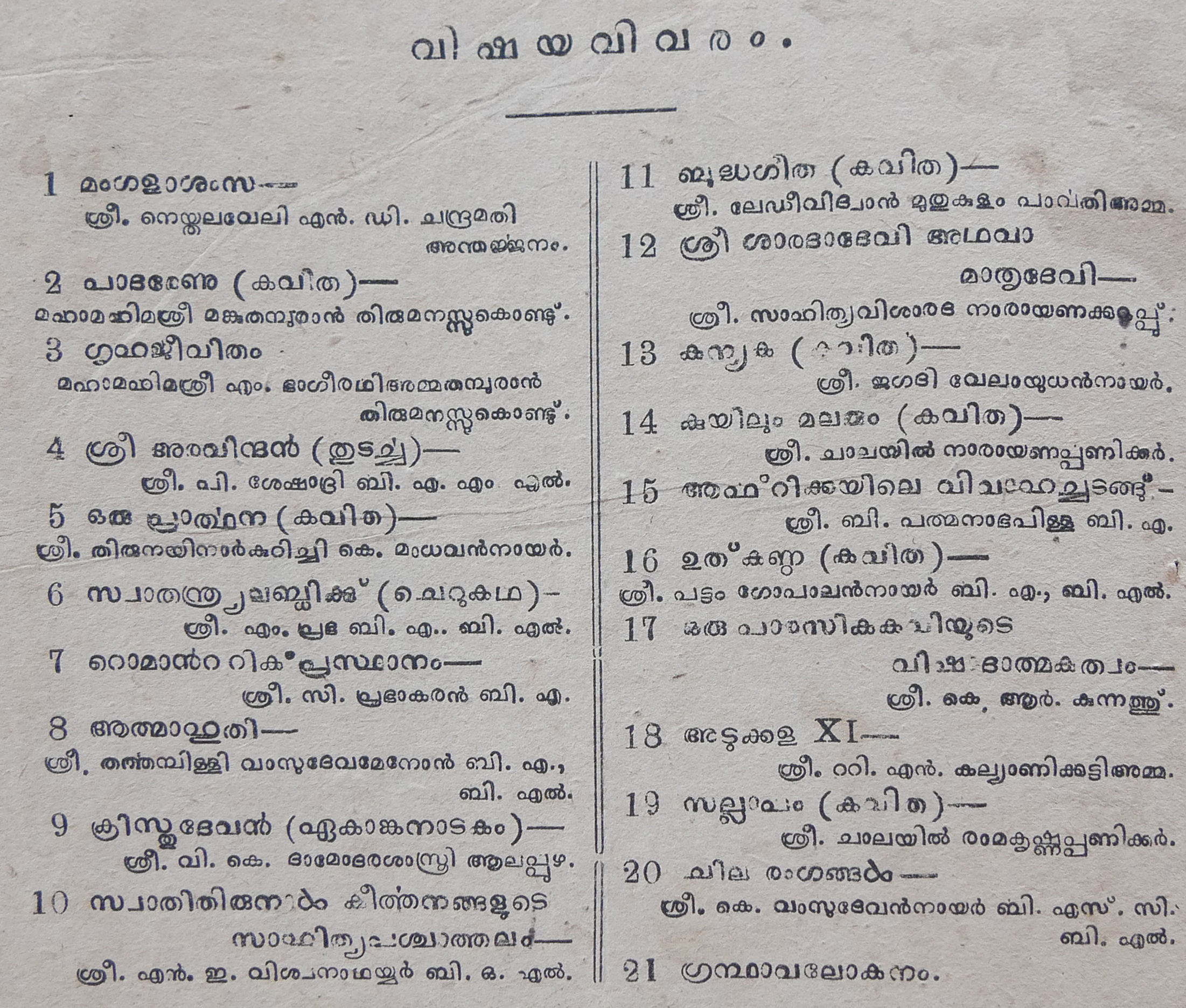

As the primary objective was women’s education and literacy, the magazines included essays on current affairs, short stories, serialised novels, poetry, tales from the Puranas and mythology, and literary critique. Furthermore, the periodicals reported on meetings held by women’s groups from different parts of the world.

Editors and writers used women’s magazines to engage in discussions, debates, and the dissemination of information they believed was relevant to women. The magazines covered a wide range of topics including women’s education, marriage, childcare, customs and rituals, household management, chastity, and fashion. They featured short biographies of notable women, as well as essays on health, contraception, medicines, recipes, and scientific topics. These magazines explored art, music, history, theology, astrology, and economics.

Lakshmibai (first year of publication-1905), Maryrani (1913), Bhashasharada (1915), Sumangala (1916), Mahilaratnam (1916), (Christava) Mahilamani (1920), Sanghamithra (1920), Mahila (1921), Sevini (1924), Sahodari (1925), Muslim Mahila (1926), Vanithakusumam (1927), Mahilamandiram (1927), Vanitharatnam (1928) Shrimathi (1929-30), Malayalamasika (1929), Sthree (1933), Vanitharamam (1942), and Vanithamithram (1944) are the magazines currently available in the various archives in Kerala. There may have been more than 25 women’s magazines published from different places in colonial Kerala.

“Lakshmibai was started in Thrissur when Kerala Varma Valiya Koil Thampuran’s wife passed away. It ran for 31 years (with breaks). It had several articles related to women and also on literature and poems. The well-known pandits of the time used to write in it, including Kerala Varma.”

– G. Priyadarshanan on Lakshmibai, 2023

Negotiating Womanhood

Supporters of women’s education had to prove that it would not make women misuse sthreeswathandryam, roughly translated as responsibility and independence. Sthreeswathandryam aimed to liberate women from traditional family roles. Global women’s movements, especially after World War I, inspired some Malayali thinkers to want the same freedom for Malayali women as Western women. Articles debated whether education would make women too individualistic and selfish, and weaken their ties to their communities and castes. It was a complex idea and certain writers saw it as dangerous and did not want women to follow the Western idea of freedom.

“Some of the writers criticise European women for the liberty they have attained and adds that luckily the idea of liberation has not attacked women in India.”

– Prof. Sreebitha, Kannur University, 2022

Clothing and Accessories

Clothing styles in Kerala used to mark caste and religious differences. In the 20th century, women were adopting new styles from the West and other regions of India. This upset traditional ideas about dress and behaviour and caused debates about culture, morality, and cost. Some writers defended the new styles as useful and proper while others linked clothing to women’s freedom and immorality.

Creating Icons

Due to the strict control over the printing press by native governments and British authority, individuals with a history of resistance against the British were not, in general, portrayed as role models. Moreover, softer qualities such as compassion, generosity, chastity, kindness, and spirituality were valued. Hence, warrior figures like Unniarcha did not find a place in most magazines. Magazine writers frequently drew comparisons between Malayali women and international women including women from the West and Asia. Asian and Russian women were positively described, more than Western women.

The magazine articles of the time conveyed a sense of belonging to the broader Indian nation, emphasising women’s role in nation-building. Women were expected to contribute by raising their children in a manner that would shape them into ideal citizens. They were also encouraged to assist the nation in various small ways, such as establishing small-scale home-based industries like weaving or teaching less fortunate women in rural areas. The influence of the nationalist movement, particularly that of Gandhi, is evident in writings from the 1920s.

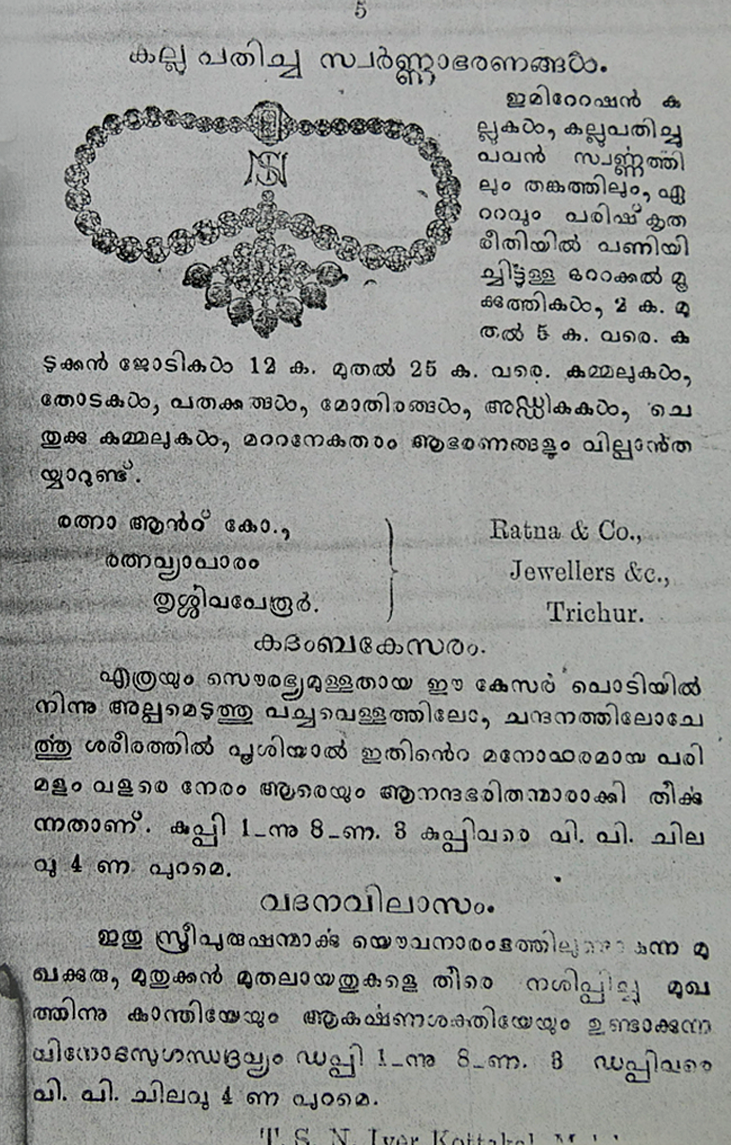

Early Consumerism

In early women’s magazines, a limited space was allocated for advertisements. These advertisements covered a wide range of topics, including hair oils, Ayurvedic medicines, treatments for various health concerns such as sexual issues and infertility, contraception, and pregnancy-related complications. There were also advertisements for clothing shops, battery and dynamo sales, rewinding services, tailoring shops, and related businesses. Furthermore, the magazines featured advertisements of other publications, magazines, and printing presses showing that manufacturers believed that there were potential customers for their products among the readers of women’s magazines.

Shift in Focus

At the outset of World War II, there was a newsprint shortage, leading to the cessation of publication of many women’s magazines. This period saw a shift of focus among the politically inclined women editors and writers toward the nationalist movement. The early women’s periodicals can be categorised as belonging to the scarce media stage. A subsequent stage, called the mass media stage by Robin Jeffrey, emerged in the 1960s when newspapers began mass production. Profitability became the driving force, displacing earlier objectives of literary and reformative content. Consequently, women’s magazines shifted their focus to entertainment rather than education. The language and essay form were adapted to the changing times and needs.

In general, the writers and the magazines were progressive in tone, discussing topics and issues related to women to a depth that one does not normally find at present. They challenged patriarchal norms, expressed their views on social issues, and wrote about gender equality, family planning, and so on. They experimented with different genres and forms of literature. Current mainstream magazines resemble lifestyle publications, while the feminist and reformative elements have formed a separate genre within women’s periodicals. These outlets employ internet-based media to cater to different audiences for the most part. Therefore, looking back to the past from the present, colonial women’s magazines appear very different from women’s magazines/periodicals in the present.

“The editorials of these early women’s magazines state their intention—to encourage women to write and contribute to the public fields. While their origins lie in the woman’s question (political debates on women’s rights/status/inequality that emerged in the 19th century) and the desire to ‘reform’ women, increasingly, we find evidence of writings exhibiting women’s views, especially since many of the early feminists of the region contributed features and articles. There are articles that refute and challenge the reformist and traditionalist views on the woman’s question in these magazines.”

– Roopa Philip, teacher at Jyothi Nivas College, Bengaluru, 2024

Our Contributors