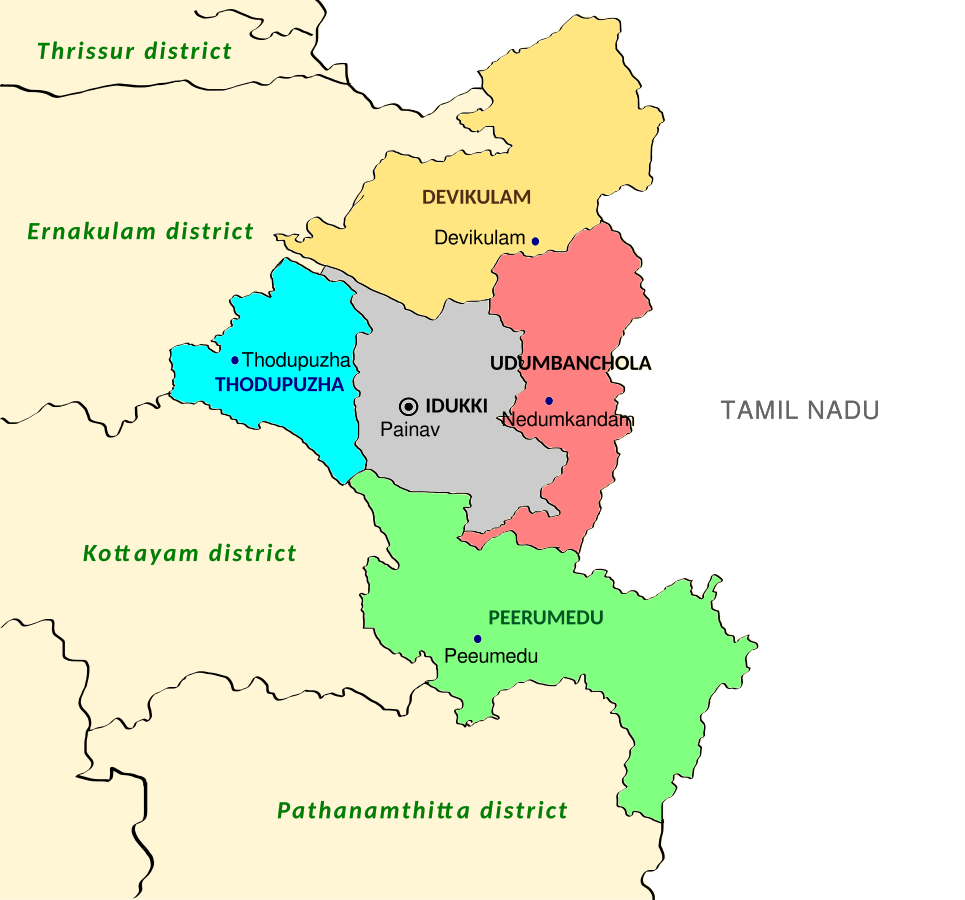

Highland Migration:

To Idukki in the Mid-Twentieth Century

Migration is viewed as an important livelihood strategy across the world for people hoping to acquire or accumulate household wealth that brings a positive change in their life situation. The concept and process of migration involves factors in both departure and destination locations, and intervening opportunities and obstacles.

North Travancore Land Planting and Agriculture Society

The Travancore Government passed the Pattam Proclamation Act (in 1865) that provided the right of ownership of land to farmers. They began to buy and sell land for agricultural practices.

In 1877, Kerala Varma, the Raja of Poonjar sold 588 sq. kilometres of the largely unexplored and thickly forested Kannan Devan hills to John Daniel Munroe, a British planter. He formed the North Travancore Land Planting and Agriculture Society. The members of the society developed tea, coffee, cinchona, and cardamom plantations and estates, initially in the Munnar region, and later in the Kumily–Vandiperiyar area.

Early Migrations

Migration from central Kerala (then the Cochin–Travancore region) began in the early 1900s when people came to work on plantations. Roads were opened, transport was organised, houses and factories were built, and production rose rapidly in the succeeding years.

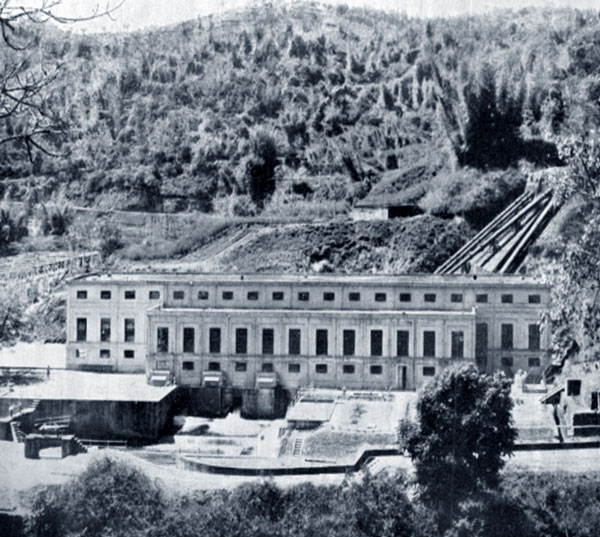

Additional areas of evergreen forests were destroyed in connection with the construction of roads, factories, etc. The Pallivasal Hydroelectric Project (1920), the first hydroelectric project of the State, was initially constructed by the tea companies for industrial use.

From 1909 to 1924 concern over forest protection held sway, and registration of cardamom lands was prohibited. Once the cut-off date in 1920 was allowed, a boom of registration and encroachment followed from 1928 to 1932.

Later Migrations

In the early 1940s, when extensive food shortages occurred throughout Travancore, the government allocated large tracts of land in the forest for paddy cultivation on an emergency basis. In the following year, the government granted exclusive cultivation rights (known as kuthakapattom), up to five acres, on a short-term lease basis.

By 1951, as many as 70,000 Malayalis had migrated from Travancore to forest areas in the high ranges. The migration of settler families to the highlands increased after the government allowed them to get full ownership rights, with conversion of their existing leasehold forest clearings to a regular pattayam-based ownership.

“The first group of migrants cultivated the new land, lived off the yield for a year, and then returned to sell their produce in the town below Idukki, making the region a trade centre.”

– George, 60, Cheruthoni, 2024

In the 1940s and 1950s, most of the migrants were Syrian Christians of Travancore from Kottayam, Thodupuzha, Kothamangalam, and Muvattupuzha regions. The custom of weekly community gatherings at their home churches allowed recent migrants to make others aware of the potential of migration. Most migrants were small cultivators who planted paddy, tapioca, rubber, and spices.

“Every migration was a gruelling experience, as people had to leave their land and families behind and move to a new area. They had to find land and adopt new methods to produce crops without knowing the outcome… After the 1930s, migration happened every year due to different reasons such as projects, floods, droughts, and so on, until the construction of the Idukki Dam. As a result, the migration kept on increasing, and people kept adapting to new challenges.”

– George, 60, Cheruthoni, 2024

Food shortages were the immediate cause of migrations for these people. Population growth, land fragmentation, and heavy dependence on cash crops, which experienced wide fluctuations, may also have been underlying factors. A shift from the joint family system to a nuclear family also required more jobs and earning opportunities, which were demanded by the increasing population.

“I came from Kothamagalam, where I was born and brought up. Before migrating here, I was working in the catering department of the Southern Railways at Madras. However, the position was not permanent, and I found it difficult to get new opportunities. I was married, and a suitable job that provided a decent living was necessary. That was when I heard of the opportunities in the high ranges from my brother.”

– Varghese A.M., 89-year-old small-scale entrepreneur, 2024

“My parents were living in a joint family, and it was difficult to live in such a small house with 5–6 children. By that time, agricultural productivity declined. So, my father went to the high ranges in search of a job and land for farming.”

– Leelama Palamalayil, 72, farmer, 2024

Migrant Memories

The town of Upputhara in the Idukki district can be called the migrant’s gateway to the highlands. Two famous Malayalam books on the Idukki migration, Highranginte Kudiyettacharitram and Malanadinte Ithihasam mention how a group of adventurous and hardworking young people first migrated to the highlands:

‘Their journey was barefoot through a forest full of stones, worms, thorns, and cobras. They had only the bare necessities and travelled in groups of eight to ten. Their goal was to encroach on the land and they lived with acquaintances until they built their shelter. The shelter was built high up on trees to protect them from wildlife at night. They used bamboo ladders to climb up to it. Their meals consisted of kappa, porridge, packed and dried channayila and kuvayila. Other food items included wild honey, wild boar, boiled squash, green bananas, and wild pumpkin.’

Image: 1956 Central Travancore (movie), 2019

Challenges

The arduous trek, lack of infrastructure, and struggle to establish themselves in a new environment are etched in their memory.

“My mother used to tell us about the difficult journey they had to take when they first came here. There was only one bus, and they had to walk for almost 3–4 hours carrying us, the children, and other household items. There was no proper road; only small mud paths to walk on, created by the men in the group. My mother had to join my father in farming, so we could have meals daily. We struggled to adjust to the conditions here, but as time moved on, it became normal to us, and now this is our land.”

– Mariyakutty Chenoottumalil, 66, Kathipara, 2024

“Cars and proper roads were not available, which made travelling a time-consuming and arduous task. It was not uncommon for people to walk for hours or even days to reach their destination.

At first I bought land in Mudiya in 1964. However, around 1970, I came to Adimali. When we first came here, we had to travel by bus, and I still remember the private bus named ‘Lilly’ that we used to take. The fare was only 1.50 paisa from Kothamangalam to Adimali, which was in stark contrast to the current fare of around 70 rupees.”

– George, 60, Cheruthoni, 2024

Cultivation

From the early 1920s to 1960s, lemon grass was one of the high-yielding products in the high-range region. It was easy to cultivate and the distillation process was time-consuming, but profitable.

“The primary cultivation back then was kandam krishi (multi-cropping on a small plot of land), lemongrass, ginger, paddy, tapioca, and other food for daily supplies.”

– Mariyakutty Chenoottumalil, 66, Kathipara, 2024

“Farming was the primary occupation at that time. We used to cultivate wheat, and to make space for it, we cleared the forests using fire. The soil here was incredibly fertile, fresh, and ideal for cultivation, even though the climate was harsh with heavy rainfall and mist.”

– Paily Kuriakose Peediyikal, 105-years-old, agriculturalist, 2024

A glimpse of the 1940s can be found in Paily Kuriakose Peediyikal’s narrative that spans decades of transformation—from forested landscapes to cultivated fields, marked by government interventions and collective efforts to build essential infrastructure.

“Around 1940, when I first arrived in this area, it was a completely different place. The lush forests were abundant with illi (Bambusa bambos), eatta (Ochlandra travancorica or reed bamboo), and other flora, and the region was home to many wild elephants.

After a while, tapioca and rubber cultivation became prominent. The crops were sold in nearby markets, which were later taken to towns such as Ernakulam or Kottayam, and Tamilnadu. The road to Adimali was built during Sir CP’s time, maybe around the 1930s, and the transportation back then was the Pankajam bus from Aluva to Munnar or the Swaraj bus from Kottayam to Munnar.”

– Paily Kuriakose Peediyikal, 105-years-old, agriculturalist, 2024

Community Building

“There were no churches or schools when I first arrived at Adimali. We had to build everything from scratch, including a small church made with eatta and other natural materials. We built other amenities, such as a hospital and school. I came to Adimali in search of a job, but there were no opportunities. I heard that if we went up the high range, like Munnar, we could own land and make money. So, I, along with a few friends, travelled to Munnar in search of land or jobs. But due to natural calamities and the presence of wild animals, we finally came back and settled in Adimali.”

– Paily Kuriakose Peediyikal, 105-years-old, 2024

Building a House

“When we first came here, my parents built a small hut with hay, and after a few years, we shifted to a small hut that was also used for the distillation of lemongrass, which was the main cultivation that yielded high profits back then.”

– Mariyakutty Chenoottumalil, 66, 2024

“In search of jobs and a better living, I, along with my wife, came to Adimali and tried agriculture, which was common at the time. But it didn’t work as planned, so I had to look for other jobs. With the help of my brother, I set up a small steel plates-business here in the middle of Adimali town. It was not successful at the start; so, after 1.5 years, I brought my wife Sisily also here. After coming here, she cultivated paddy, ginger, and so on. While I managed the shop, she managed the farming. For almost 10 years, the struggle was real. We stayed in a rental house for about 4–5 years. After that, we built a house and life came back to normal.”

– Varghese A.M., 89, Adimali, 2024

Human-Wildlife Interaction

“Back then, there was not much interaction like today between animals and people because there was so much land for them to roam freely. Even the wild elephants were not as aggressive back then.”

– Thomas Kaattachara, 81, Adimali, 2024

“In the beginning, it was typically the men of the family who went first. They built tree-houses, as the region had many wild animals at the time. They stayed there for a while until they got used to the local environment.”

– George, 60, Cheruthoni, 2024

Tree-house. Image: 1956 Central Travancore (movie), 2019

Migration memories to Idukki offer insights into how individuals or communities negotiate new environments, adapting language, traditions, customs, and social practices. Examining these dynamics can contribute to existing theories on migration as an economic phenomenon and elucidate the role of social networks and support systems in facilitating or hindering the migration process.

Many thanks to Paily Kuriakose Peediyikal, Varghese A.M., Thomas Kaattachara, George, Mariyakutty Chenoottumalil, and Leelama Palamalayil for contributing to this article.

The exhibition is based on the Janal Article: Janal Team and P.T. Eunisa. “Oral History of the Mid-twentieth-century Migration to Highland Kerala”. JANAL Archives, 2024.

References

Jennissen, Roel. ‘Causality Chains in the International Migration Systems Approach’. Population Research and Policy Review 26, no. 4 (August 2007): 411–36.

Kurias, J. High Ranginte Kudiyetta Charitram. Idukki: A.K.C.C Diocese of Idukki, 2012.

Lee, Everett S. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3, no. 1 (1966): 47–57.

Mannarakam, Mathew. Malanadinte Ithihasam. Kottayam: Turn Books, 2019.

Moench, Marcus. ‘Politics of Deforestation: Case Study of Cardamom Hills of Kerala’. Economic and Political Weekly 26, No. 4 (1991): 47–60.

Pillai, N. Kunjan. Census of Travancore. Director of Census Operations, Kerala, 1931.

Rajasenan, D. ‘Livelihood and Employment of Workers in Rubber and Spice Plantation’. In NRPPD Discussion Paper. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Development Studies, 2010.

T, Rajesh. Idukki Charithrarekhakal. Kattappana: E-lion Books, 2008.

Varghese, V.J. ‘Land Labour and Migration: Understanding Kerala’s Economic Modernity’. Working Paper 420. Thiruvananthapuram: Centre for Developmental Studies, 2009.