History of Women’s Education in Colonial Era

Kerala has a high literacy rate (92.07% in 2011) and women’s education levels in the state have been high since the early twentieth century. The high literacy and educational statistics for women are a result of initiatives by missionaries, social movements, population patterns, community reforms, and policies by local kingdoms and the British in Malayalam-speaking regions since the early 1800s.

Colonial Rule and Modern Schooling

In 1813, the Charter of the English East India Company was revised, allowing British missionaries to conduct mission work in India. The company faced criticism in England and shifted from a commercial focus to a form of colonial rule. Education was to play a significant role in this transformation.

Protestant Christian missionaries began working in Travancore, Cochin, and Malabar alongside the expansion of British rule in these regions. In the following decades, missionaries arrived in other parts of Kerala and started mission centres and schools.

Travancore Rescript of 1817

A system of education in single-teacher schools called ezhuthupallis existed in the Malayalam-speaking regions. There were also Vedic schools, kalaris, madrasas, and a tutoring system at home which were not accessible to all castes and classes.

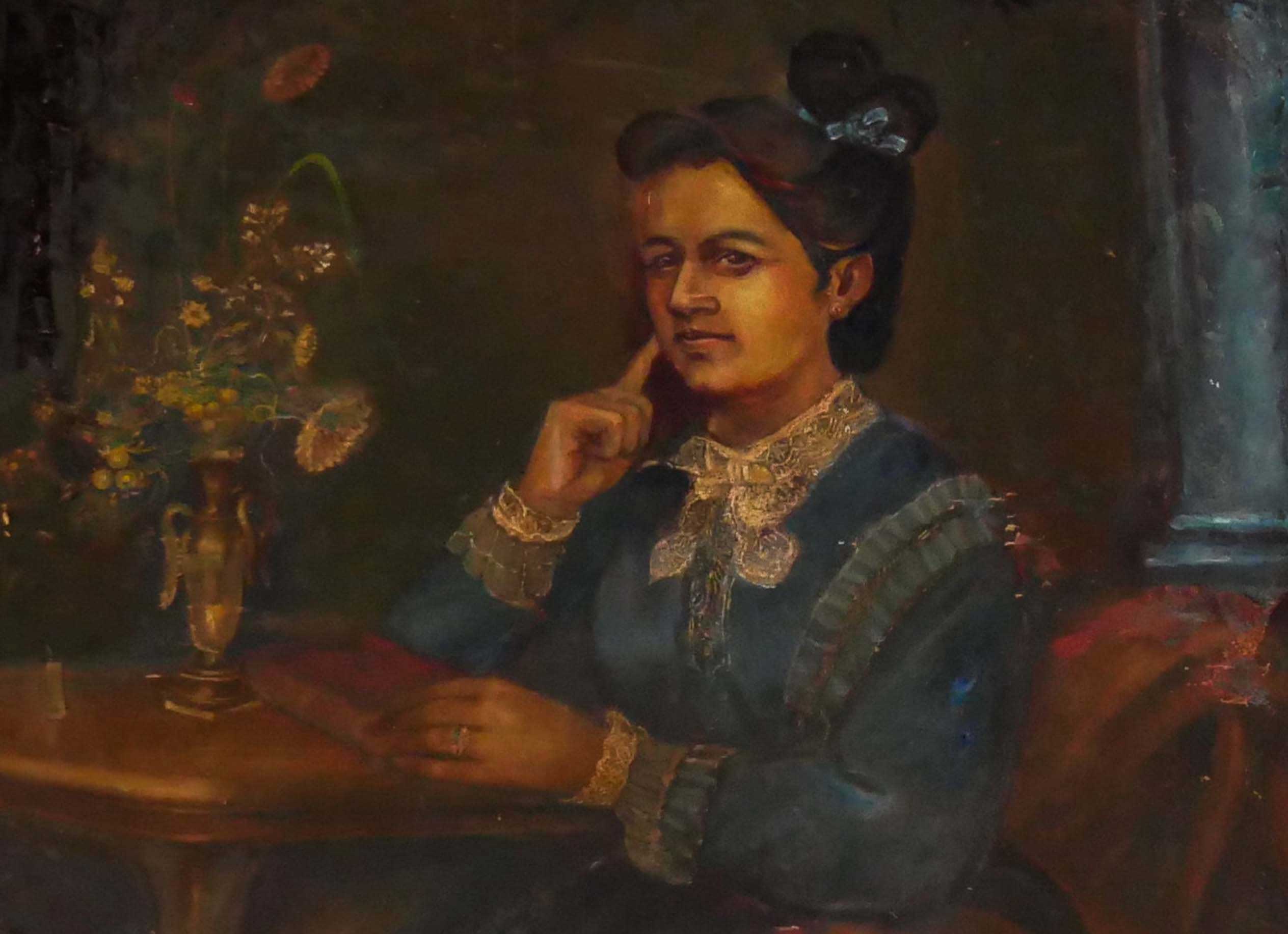

The issuance of a Royal Rescript on education in 1817 by the Regent Rani Gouri Parvathi Bai of Travancore proclaimed that the state would bear the entire cost of education. This was the first formal recognition of education as part of the state’s administrative responsibility.

She was supported by Colonel Munro, the British Resident who was interested in starting schools in Travancore and Cochin.

Where was the first school started in Kerala?

The first missionary to arrive in Cochin was Rev Thomas Dawson. His wife, Mrs Dawson, worked with the women in the area. They started two schools in Fort Kochi, one for boys and one for girls called the Protestant English Boys School and the Protestant English Girls School in 1817.

"One of the Raja’s children used to study in this school,” – Rosemeera, Headmistress, St Francis Church L.P. School, Fort Kochi, 2023

The Dawsons’ schools were built behind the St. Francis Church in Fort Kochi, which had belonged to the Church of England. They believed that female education was essential for the progress of the country and to instill Protestant Christian ideals in them. The schools provided basic education with religious instruction and vocational training. Boarding schools were started to keep away students from non-Christian influences.

The Raja’s child who studied in the school at Fort Kochi later converted to Protestantism.

Kinds of Schools

Various types of schools were established by the missionaries, including seminaries, normal schools (advanced learning and teacher training schools), boarding schools, day schools, high schools, and others. Another group of schools was the Nair Schools, established in response to the Nair community’s request. These schools provided education to both boys and girls. Additionally, there were Anglo-vernacular, night, and evening schools to cater to those engaged in manual labour during the day.

Subjects and Teaching

The schools offered courses based on the teachers own experience of traditional English education. The children were given instruction in reading and writing the vernacular language with religious instruction and vocational training. Talented students received special training in English.

The girls learnt practical skills such as spinning, knitting, sewing, and embroidery. The primary focus was on training them to be good mothers and homemakers. Later, missionary education provided practical skills and exposure to the world through history, geography, and natural philosophy.

Modern Education and its Apprehensions

In south Travancore, lower-caste converts faced opposition on adopting upper-caste customs under missionary guidance, sparking early movements against caste restrictions. In contrast, the northern missions faced opposition from Syrian priests over religious differences, resulting in a ban on Syrian Christians attending Protestant mission schools after 1837. Missionaries in both Travancore and Cochin faced caste-related obstacles, as upper-caste members were reluctant to allow their children to mingle with lower-caste children in schools.

The Malabar region experienced a delay in adopting modern English education. The Mappillas, or Muslims in the area, viewed the British as oppressors. This led to resistance against the English language and Western education. Fear of conversion by Christian missionaries further slowed the spread of modern education. Influential Muslim theologians opposed schools, particularly for girls. The Namboothiris, a locally prominent community scorned the English language. Moreover, the British rulers of Malabar were indifferent towards the development of primary education.

Julie Gundert, the wife of Hermann Gundert, started a girls’ boarding school in Tellicherry in 1839. Some of the students in Malabar were children of Christians who had migrated from Tamilnadu.

"Very little has been done for female education" – Madhava Rao, Diwan of Travancore, 1863.

In 1859, the Madras government sent a letter to the Travancore government, highlighting the numerous abuses and issues prevailing in the region. The letter advised the government to take an enlightened approach and implement reforms to avoid impending calamities.

In 1864, a school exclusively for higher caste girls was established. Progress in education in Travancore occurred during an economic boom brought about by the commercialisation of agriculture, land tenure reforms, and other modernisation programmes in the 1860s. This allowed the Travancore government to spend on social reform, particularly education and healthcare.

"The new Maharajah sent 30 rupees for prizes at the annual examination."

“We have had a very good and uninterrupted year of study and far more regular attendance than ever before. The first class, consisting of nine girls, was examined by the Walia Coil Thampuran, husband of the Senior Rani, and in history of India and geography of Travancore by the Malayalam Munshi of the High School and College”, wrote Miss A.M. Blandford, Headmistress, Zenana Mission School in 1864.

By the turn of the century, missionary schools had to follow the Madras government curriculum, which included learning multiple languages. This last was despite their disapproval, as they wanted their students to be eligible for the matriculation examinations. Thus, slowly the objective of education shifted to students pursuing advanced learning and new job opportunities.

In Malabar, girls were taught a variety of subjects, including mathematics, English and other languages, history, scriptures, and singing. By 1912, some schools introduced courses on housekeeping, hygiene and elementary nursing for girls, and gardening and darning for both boys and girls.

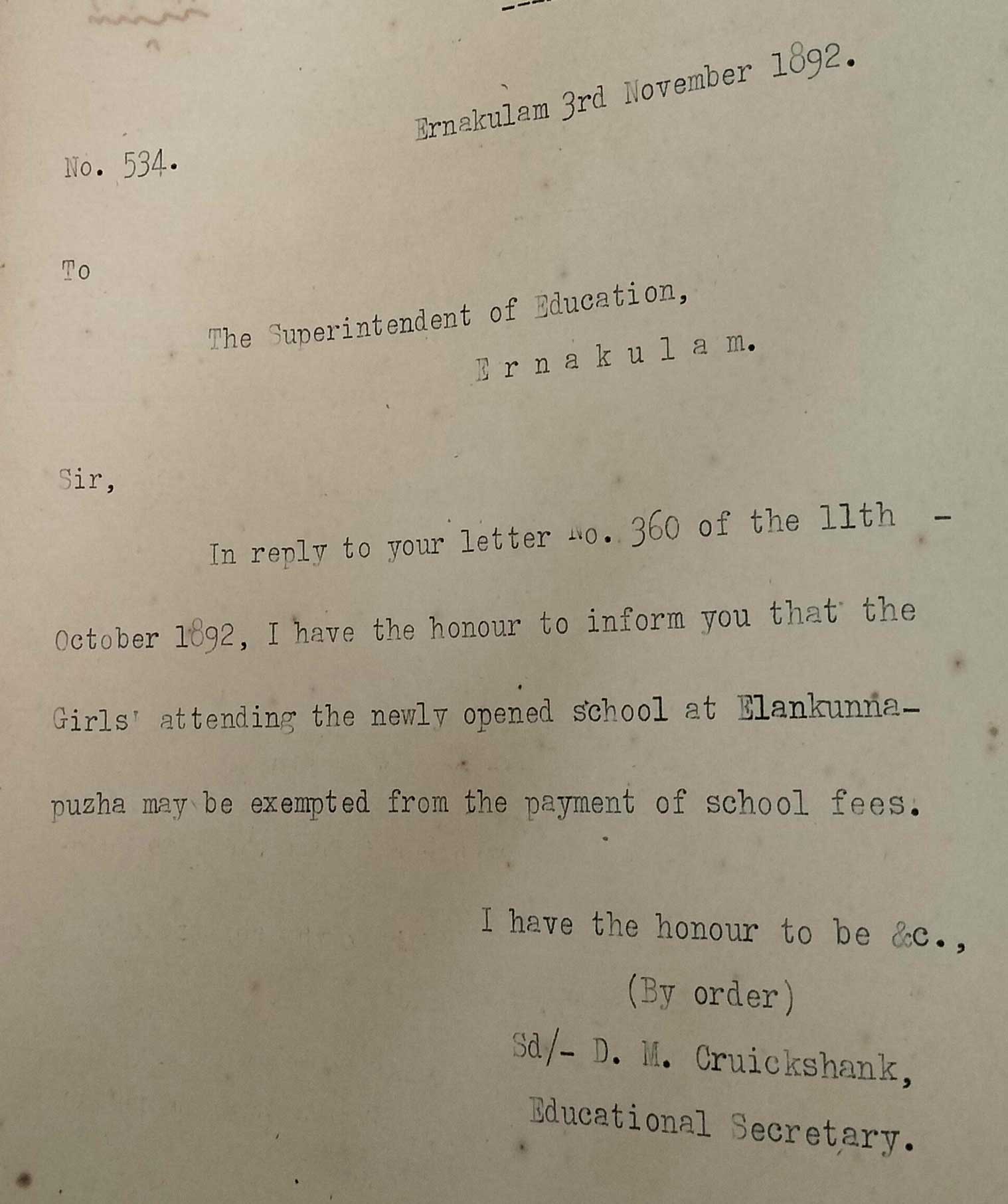

Controlling School Education

In 1894, the Travancore government introduced a new grant-in-aid code for schools in the State, bringing the educational system under one authority. The code disqualified many teachers and required schools to have better buildings and furniture and a higher average attendance. Schools that did not meet the requirements of the code were denied grants.

By the early twentieth century, many Missions had already transferred their schools to the government or local organisations. The governments’ involvement reduced the disparities that existed between the education of girls and boys.

"Girls from all communities and religions used to study here," – Chetan D. Shah, Manager, Sri Gujarathi Vidyalaya HSS, Mattancherry

The re-organisation of women’s education began with the appointment of a Female Inspectress of Schools in 1908. Many castes and communities saw education as necessary for the upward mobility of community members.

Organisations like the Nair Service Society, Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham, and Lajnathul Islam Sabha started schools. The Gujarati community in Cochin started a school for girls in 1904, which was recognised in 1919.

The Haji Essa Haji Moosa Memorial HS started in 1936 in Mattancherry to cater to the educational needs of the Muslim community. “There were girls in the school from the beginning,” said the school’s headmistress, Sindhu. The school was open to all communities, with teachers and students from the Brahmin community joining in the initial years.

Confronting Prejudice

By the early twentieth century, women’s education in Kerala faced different challenges compared to men’s education. Separate schools were established for the backward classes, and most schools admitted Ezhava boys in the early twentieth century, but the girls of these communities were not admitted to any of the schools. Caste prejudice was more apparent in the education of girls than boys.

Co-education policies resulted in Malayali women entering public spaces previously dominated by men, which elicited mixed reactions from the students, parents, government and school authorities, and the public.

Hygiene, Nutrition, and Exercise

There was a fear that being confined to the classroom would affect the health of the students. Care of the body was a response to prevalent debates about the unhygienic practices and the frequent outbreak of epidemics. Exercise, sports, and games came to be connected to health.

Schools began to appoint drill masters in addition to subject teachers. Additionally, conducting sports events and winning prizes was a matter of prestige for educational institutions.

Same Schools and Subjects for Boys and Girls

By the 1940s, most girls were studying in boys’ schools and not receiving segregated education. Though the idea of gender differences persisted, schools and colleges could not offer different subjects to boys and girls.

During the global depression and war years till 1945, technical education was seen as a solution to economic challenges.

The government promoted technical education to improve livelihoods and modernise the state’s economy, emphasising practical skills over purely literary education to meet the changing job market demands. The Travancore Education Reorganisation Committee 1946 emphasised basic education for both sexes.

Thus, the remarkable progress of women’s education in Kerala results from a complex interplay of various policies, factors, and players that have shaped the state’s social and economic development from colonial times.