"We always pray that it doesn’t rain, and if it rains, the sea doesn’t come to us". ... Thresiamma, Chellanam resident, 2022.

Chellanam, a coastal village 40 kilometres south of Kochi, is a strip of land between the Arabian Sea and the backwaters. Until a few decades ago, it had a beach that stretched 3 kilometres into the sea. Large tracts of sandy beach separated the sea and the villages. Since then, the sea has started advancing to the nearby towns, and coastal land has begun to erode due to the removal of sand and sediments from the shoreline.

Today, the beach has disappeared, and this village faces the impetus of an increasingly erratic monsoon, floods, and cyclones. The low-lying region gets inundated with seawater, and waves crash into homes and seawalls, destroying homes and lives.

Because of its location, the whole area is highly susceptible to coastal erosion and was marked as such by the state government in 1986.

THEN, “About 30 years ago, our children used to play football at the beach”. … Philomena George, Chellanam native.

NOW, “The distance between the coast and sea decreased drastically after the 2004 tsunami.” … Carpenter Josey, Chellanam native.

Waves break on the tetrapods on a stormy day in Chellanam. The tetrapods are the latest addition to the measures to secure the coast of Chellanam from floods and erosions. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

Thresiamma, a resident of Chellanam, narrates her experience of surviving the floods and erosion of Chellanam. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

A part of the former Kingdom of Cochin, the popular tale behind Chellanam’s origin goes back to Tobias Kapithan, who was presented with a piece of land called Chellavanam, a forest without any traces of human habitation, by the Maharaja of Cochin where he settled with his family and the name was shortened to Chellanam.

Predominantly, Latin Catholic Christians inhabit the village, with a minority of Kudumbi Hindus. The Kudumbi Hindu population is the descendants of Konkan Sudras who migrated from Goa due to Portuguese persecution in the 16th century and sought refuge along with their masters, Konkan Brahmins, on the coast of Travancore and Cochin. The most respectable elders of the community were conferred with the title Muppan by the kings of the Royal Family of Cochin.

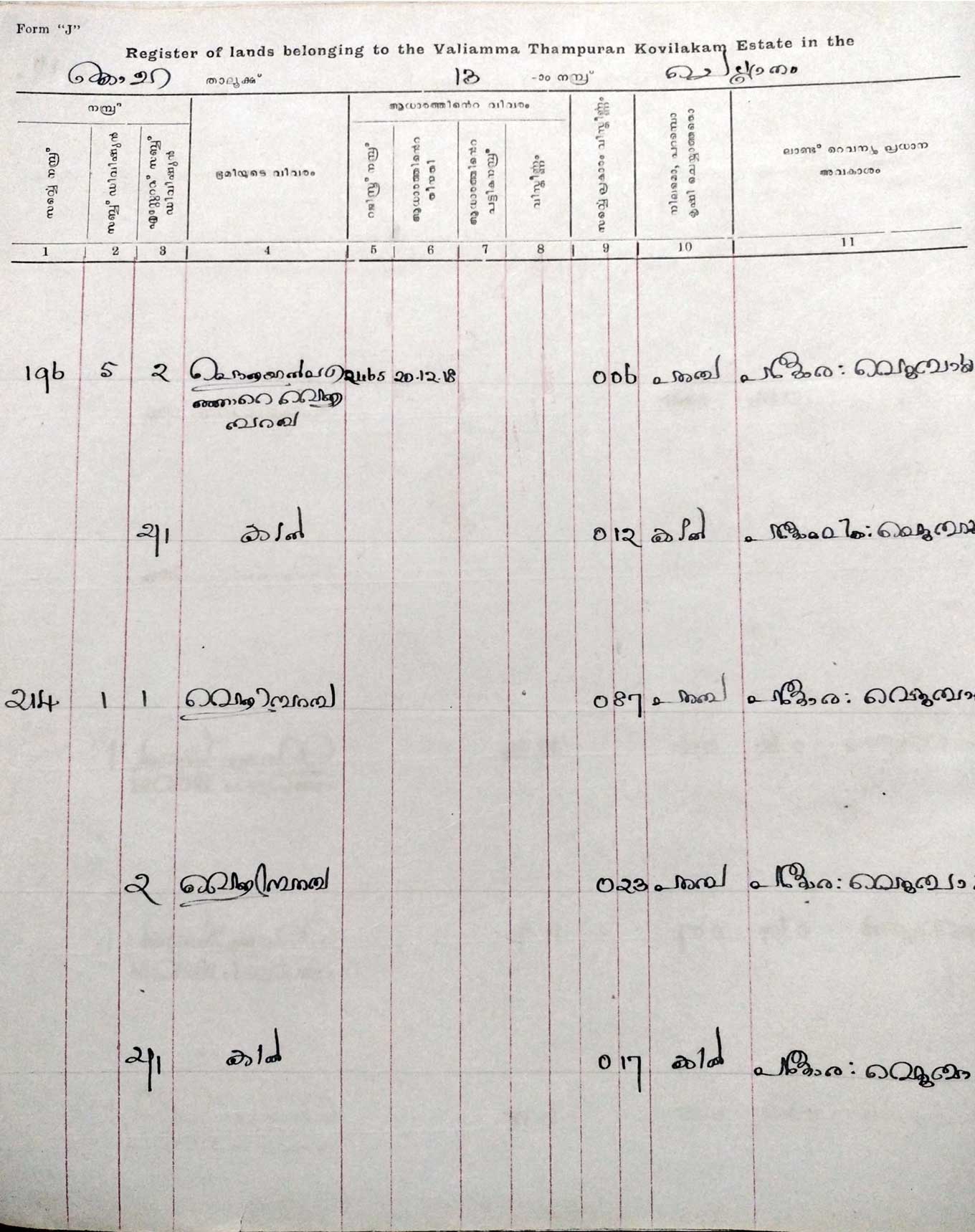

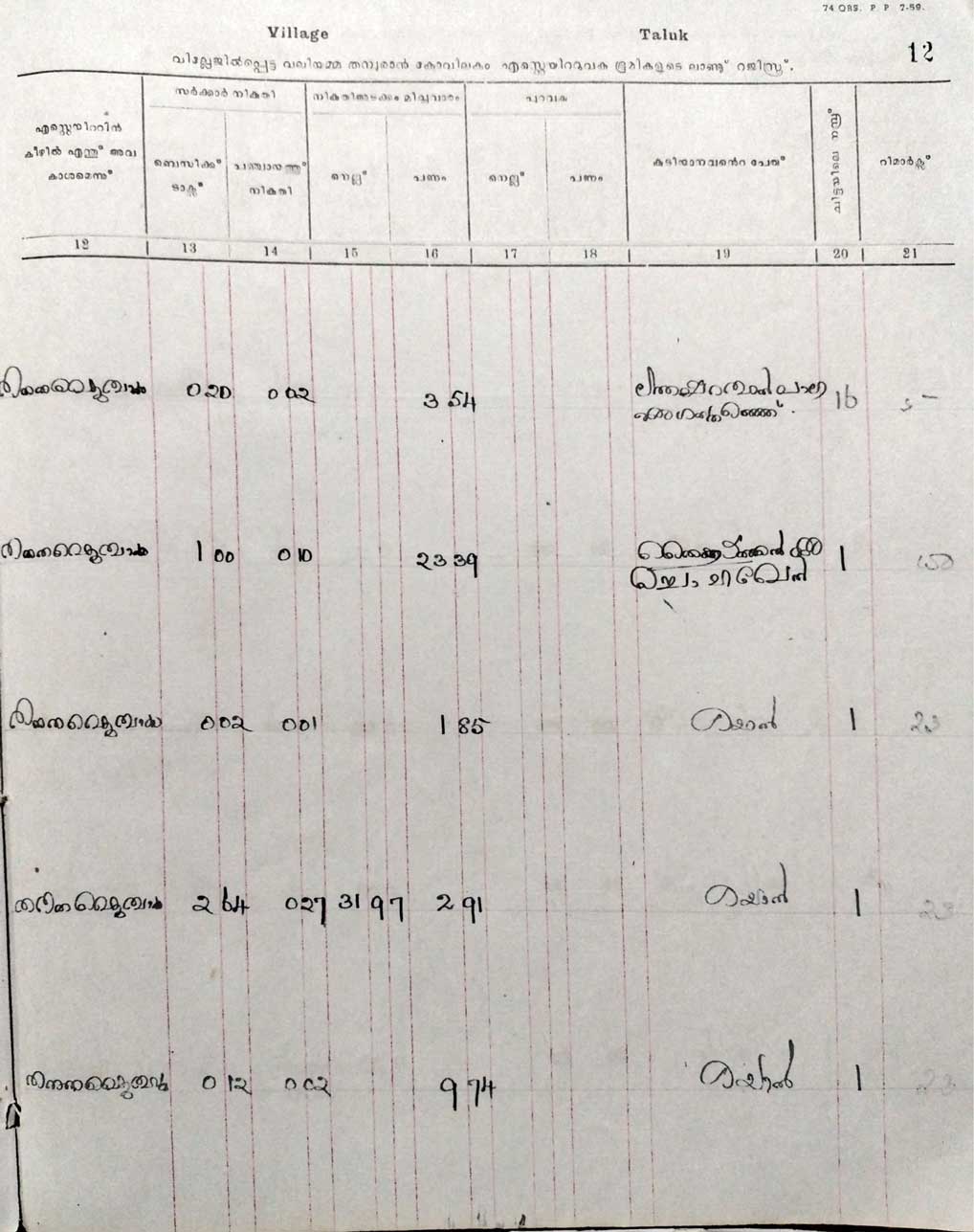

Following the legislation of Valiamma Thampuram Kovilakam Estate and the Palace Fund (Partition) and the Kerala Joint Hindu Family System (Abolition) Act, 1961, many landholdings of the Royal Family, including the ones in Chellanam were partitioned. In subsequent years, these properties were passed onto the tenants whose families currently inhabit the village of Chellanam.

In the early 1960s, the Valiamma Thampuran Kovilakam trust under the Cochin Royal Family sold their land holdings in Chellanam to the residents. This image describes the details of the land on sale. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

This image includes the details of land tenancy and details of locals to whom the land was sold. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

The current map of Chellanam Village and its subdivisions. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

The Chellanam Fishery Harbour is an artificial basin harbour 250m west of the Thoppumpady-Chellanam State Highway. Image: JANAL Archives, 2023

“The silt deposited during the flooding would reach the level of the windows.” ... Benson, Panchayat Secretary.

Hundreds of families regularly lose houses and other valuables due to rising seawater levels and saline water intrusion. Wave setup is a term for the rise in the water level within the surf zone as the waves break on the shore. A rise in the coastal water level due to wave setup causes the inundation at Chellanam. Until last year, the village was on the verge of destruction due to the flooding caused by this phenomenon. The sea engulfs about 10-15 houses yearly, and devastating waves wreak havoc by depositing silt and other debris in the homes of the coastal community.

The floods leave behind ruined houses that are unsuitable for living. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

Victoria and Matthew stand outside their damaged house. Over 20 houses were destroyed in their locality in 2022. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

"The dredging machines sank in the sea because the sea floor had lost its volume and subsided.” ... Sinuja, Chellanam Resident.

For over five decades, erosion of large expanses of property owned by the local community has occurred in this area. A few studies report that the erosion of the Chellanam coast started with the Cochin Port Trust’s dredging, including increasing the depth of the off-port channels. Offshore dumping of the dredged material does not help replenish sand on the Chellanam coast and aggravates the local coastal erosion in Chellanam. Due to this occurrence, the locals of Chellanam assert that the flooding is an artificial disaster.

The lost shore: A significant and jarring visual of the waves eroding the shore. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

The view of pulimuttu from the coast. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

"The erosion and flooding are the consequences of the functioning of Cochin port and Chellanam harbour." ...Shirlie, Chellanam Resident.

Along the coast, activities such as the construction of hard structures (breakwaters, seawalls) and dredging of channels can have a negative impact. They obstruct the natural flow of the water and sand, causing erosion on one part of the land and deposit on another.

At Chellanam, locals attribute the establishment of the Chellanam Harbour and Cochin Port as the major cause of this phenomenon. Ships arrive and depart the port through the shipping channel. The dredging of the channel occurs regularly to maintain its depth. The sand and sediments from Chellanam get trapped in the channel and deposited in the deep sea. This process changes the sand movement ecosystem and causes erosion.

“Additionally, there has hardly been any attempt to maintain the seawall in recent years compared to the local attempts a few decades ago,” continues Shirlie, a Chellanam Resident.

Man clearing the slit from a house ravaged by the flood. Photo taken during the restoration process after the flood. Image: George Babu, 2022.

Ruined houses at Chellanam. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

Confronting coastal erosion

While the giant tetrapods are a recent development to build a seawall to protect the Chellanam coast, there have been initiatives in the past to curb the strong waves hitting the shores, like the construction of the pulimuttu (breakwater) structures that extend perpendicularly into the ocean. These structures reduce coastal erosion caused by water currents, which move parallel to

the coast and break the flow of strong waves hitting the beach.

According to George Babu, a retired Navy man active in rehabilitation activities since the 2018 flood, these structures had existed in Chellanam for 40 years, and flooding was not as common as it is now. Since then, wear and tear has submerged the pulimuttu, causing the seawall to take the direct hit of the waves. He added that if these structures do not extend to the northern borders of the Chellanam Panchayath, the residents of that area will have to face the dire consequences of flooding.

The relative permanence of sea walls along the coast and pulimuttu gives a sense of assurance that these hard erosion control structures can be a final solution to erosion. However, the likelihood of sea level rise in this area inundating hard structures has highlighted natural forms of hard-erosion control, like mangroves and other native and economically useful species.

Local attempts to minimise damage to lives and homes

After the disaster, rehabilitation involves cleaning and rebuilding the houses and treating the locals affected. Schools convert into relief camps overnight in these situations, and some people stay on the top floors of their homes when it floods. Flooding has become so common in Chellanam that people prepare by sending the children and elderly to their relatives’ places whenever a warning is issued.

According to Father Sibi of St. Sebastian Church, people’s collective efforts help the evacuation and rehabilitation run smoothly. He explains how, in 2021, the situation was so dangerous that people had to be evacuated forcefully from their houses as they refused to join the camp because of COVID-19.

St. Sebastian church Chellanam. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

Father Sibi at Chellanam Church. Image: JANAL ARCHIVES, 2023

"Living with uncertainty as current solutions are temporary." ...Kunjupennu, Chellanam resident.

While the villagers accept the sea wall, they are concerned about the construction quality. They believe the flood is an artificial issue as the village has survived all these years without official intervention. They also complained about the authorities’ lethargy, as funds are passed yearly but never implemented.

"Living with uncertainty as current solutions are temporary." ...Kunjupennu, Chellanam resident.

While the villagers accept the sea wall, they are concerned about the construction quality. They believe the flood is an artificial issue as the village has survived all these years without official intervention. They also complained about the authorities’ lethargy, as funds are passed yearly but never implemented.