Thrissur Corporation

The only corporation in Kerala that distributes electricity

Cochin State in the beginning of the 20th century, was experimenting with a variety of modern industries, in line with the era of industrial modernism prevalent across the globe. However, the State did not have adequate electricity generating stations to supply its industrial demands.

C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer, Dewan of Travancore drew attention towards the Sivasamudram Hydroelectric project inaugurated by the Mysore State in 1902, which enabled the electrification of Mysore and Bangalore. Mahatma Gandhi, who was apprehensive of electricity being diverted for urban and industrial needs, was vocal in his support of spreading the scheme to rural areas.

Electric Power in Kerala

“The earliest power generation was done to meet the demands of the plantation sector in Kerala.”

– Vignesh P., 2024

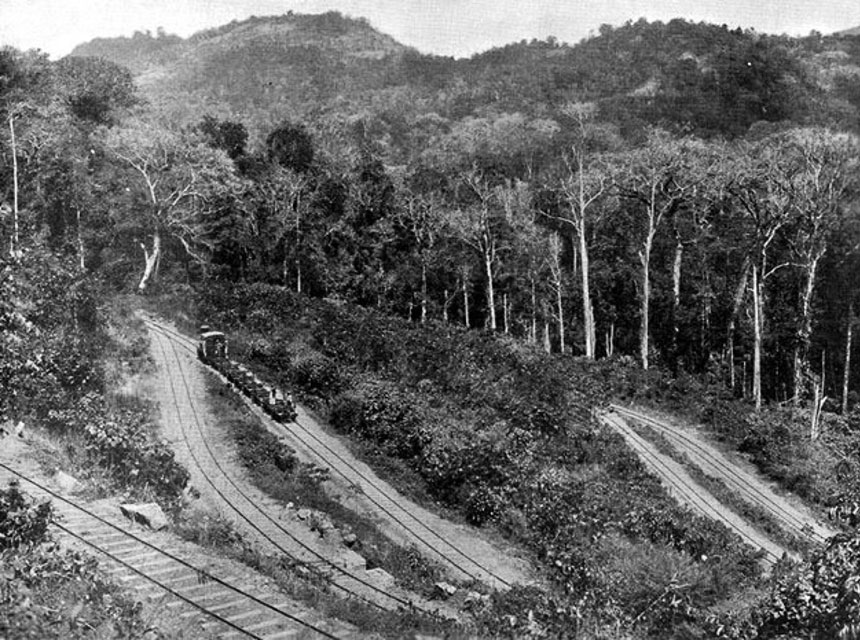

The Kannan Devan Hill Produce Company’s initiative in 1900 to establish a hydroelectric project on the Muthirapuzha and Periyar rivers was a significant step towards self-sufficiency in electricity for their plantation operations. By 1931-32, the company operated 22 miles of 11 kV and 30 miles of 22 kV transmission lines.

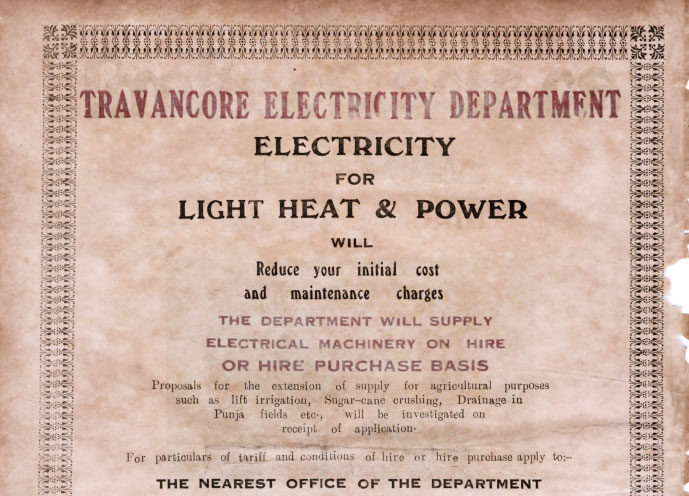

Similar efforts at electrifying large areas were undertaken by the Travancore government in the early 20th century, where engineers and foreign technical expertise enabled the state to come up with a blueprint for a hydroelectric project.

“The Trivandrum Electric Supply which supplied power for street and domestic lighting and for lights and fans in government offices, was the earliest among them.”

– E.T. Mathew, 1977

Early Attempts at Electrification

The state was also looking at ways to generate cheap electricity. The waterfalls in the Chalakudy River were scouted, and the scheme was put into motion in 1918. However, by then, several private electrical companies were operating in Cochin and Trichur.

With the introduction of hydroelectric projects along with thermal power plants in the plantations, the power output increased considerably. The Indian Electricity Act of 1910 allowed private companies to set up shop and distribute electricity. However, the supply of electricity to large networks proved to be a problem. The huge costs incurred for infrastructural development and electricity charges angered the public and obstructed the massive deployment of electricity.

“It was said that there were more power cuts than power supply in the early days.”

– Vignesh P., researcher, 2024

“It is said anecdotally that electricity was first distributed in Kerala from the palace of the Travancore Maharaja. They had a diesel generator and had excess power. The Maharaja looked up the list of the prominent men in the city and forced the people that topped the list to buy the excess power.”

– A Kerala State Electricity Board engineer (KSEB), Thrissur, 2024

The Electrification of Trichur Corporation

The Thrissur Municipal Corporation was instituted in 1921 to oversee the town’s developmental ambitions. A town council, which existed since 1910, managed the affairs before that.

The electrification project of the Thrissur Corporation commenced with a powerhouse at Kottappuram, Thrissur. The government authorised M/s Chandrie and Company Ltd. to distribute electrical supplies in the Thrissur town area.

In 1933, the establishment of an independent electricity department by the Maharaja of Travancore marked a major milestone in Kerala’s electrical history, fostering subsequent advancements.

“The diesel generator at Kottapuram was used to supply power to the town. Soon after, a protest followed in the town on giving the license to Chandrie and Company because the company could not manage the distribution, and later it was decided that the municipality would take over the job of power distribution.”

– Shanmukhan C., Rtd. Senior Superintendent, Thrissur, 2024

Electricity for Farmers

The TCED, earlier known as TECL, distributes electricity within the old Corporation limits. It is authorised to distribute electricity under the Central Electricity Supply Act and is the only local government body in Kerala to distribute both electricity and water.

The Poringalkuthu Hydroelectric Project was initiated with the purpose of including Ernakulam and Thrissur in its grid. By this time all the major towns in Cochin state had an electric company to supply their energy needs. But in Thrissur, the company had a different purpose—de-watering ‘ kole’ wetlands for farming.

“Kole lands, or “bumper yield lands” are wetlands in Thrissur and Malappuram districts, watered by the numerous lake and river systems adjoining the region. A rough translation of kole, which Malayalis use as a figure of speech, is to show excitement or highlight their luck. Most of the time, these lands are available for cultivation, with only a few portions submerged. However, with the coming of steam-operated dredging machines, it was possible to reclaim more land from water for cultivation.”

– Vignesh P., researcher, 2024

Draining Wetlands for Farming

The kole farmers presented a memorandum to the state to institutionalise the tax base of kole cultivation and ensure a regular supply of steam dredgers for draining the field in 1914. The demands for rationalising this arrangement continued up till 1926, when the government convened a Kole conference to discuss how to improve cultivation. Thus, the initial requirement for electricity in Thrissur was for agricultural use.

Meanwhile, supply from the Pallivasal hydroelectric project in Travancore began in 1942.

“In 1949, the Pallivasal project was producing more electricity than was required. So, they asked TCED if they could buy from them. A tripartite agreement was reached between the Pallivasal project, the electricity board, and the Thrissur municipality, and electricity started to be supplied from this project to Thrissur. We stopped generating from Kottapuram after that.”

– Shanmukhan C., Rtd. Senior Superintendent, Thrissur, 2024

Unique requirements at Thrissur

Some of the major cities in British India were electrified by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. At Thrissur, the expenses connected to infrastructure and maintenance of street lighting were subsumed under the expenses of the TCED, while in other places, it is borne by the village or town administration.

Like the Kannan Devan Hill Produce Company, which operated in Munnar and offered its services initially for economic purposes, the TCED achieved the unique position of being able to coordinate several economic activities that required electricity. The number of agricultural and experimental research stations put up by the Cochin government shows how Thrissur was integral to the agricultural productivity of the state. Furthermore, there were industries that were closely tied to the agricultural sector in Thrissur. The convergence of these agro-industrial requirements made the work of TCED important for the economic robustness of the state. Compared with other electric companies, TCED was the only one that was allotted the responsibility of de-watering kole lands.

“One of our linemen, Jayadevan, developed an automatic lighting switch system that was implemented in all the areas under the municipality, before the KSEB even thought about moving towards automatic switches. We still use that indigenously developed design.”

– A TCED employee, Thrissur, 2024

“The Anjuvillakku has not been working for nearly 10 years now. They should change the design of the lamp shade to minimise water seepage. Repeated complaints to the TCED have not yielded any results.”

– A shopkeeper, Thrissur, 2024

Relationship with State Electricity Board

In 1980, when TCED placed the first sub-station, there was disagreement with the KSEB regarding tariffs. In 2008, both entered a compromise, and now things are fine and most decisions are taken with the implicit approval of KSEB.

During the time of Chief Minister Karunakaran, the government tried to take over the water supply. Due to widespread protests, it was returned to the municipality. Hence, there were no strong moves to absorb the TCED to the KSEB.

The smaller size of the organisation and relative autonomy have led to various innovations in the distribution and billing processes, including the adoption of an Oracle-based billing process, much before the KSEB switched to e-payment, pointing to how de-centralisation works in the people’s favour when it comes to utilities.

“Last year (2023), TCED was selected as the best organisation in the public sector. A Rs. 136 crore programme grant was given to TCED.”

– Shanmukhan C., Rtd. Senior Superintendent, Thrissur, 2024

Many thanks to Vignesh P., Shanmukhan C., N.K. Krishnakumar, and other TCED staff.

Exhibition Research & Content: Vignesh P. and Janal Team, Kerala Museum 2024

This exhibition is based on the Janal Article: Vighnesh P. “The Logic of Power: Electricity Production in the Cochin State”. JANAL Archives, 2024.

References

Bhaskaramenon, R. “Electricity vakuppum athinte vallarchayum.” [The electricity board and its growth]. Trichur Municipal Electricity Department Silver Jubilee Souvenir. Trichur, 1962.

Bhattacharya, Debjani. Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta, New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Joseph, Sebastian. Cochin Forests and The British Techno-Ecological Imperialism in India, Delhi: Primus Books, 2016.

Kerala State Electricity Board Ltd. ‘KSEB: Charithravum Varthamaanavum’. YouTube, 4 January 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sn28Qrq-rsE&list=PLBAHBBC0_45FOiF-Y1S2WFwXMNs03S9WL.

Mathew, E. T. “Power Development in Kerala.” Social Scientist 6, no. 2 (1977): 52–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3516684.

Menon, V.K. Kunjan. ‘Kolekrishi’, Mangalodayam, 1089 M.E. (1914), 1.

Report on the Administration of Cochin for the Year 1089 M.E. (16 August 1913 to 16 August 1914), Ernakulam: Cochin Government Press, 1914.

The Cochin Electricity Act (III of 1102 M.E), 1927, C.207, E.R.A.