There was a time when it sort of lost its importance. I am happy to see that people are more aware of Chavittunadakam now, so in a sense, this can also be seen as its rebirth.” - Josy, Chavittunadakam writer, director, and performer, 2023

The emergence of Chavittunadakam is believed to have taken shape between the 17th and 18th centuries. This art form illustrates the transformation Christianity underwent in Kerala, spurred by the Portuguese presence. Many researchers have pondered over its origins, with consensus pointing towards the role of Latin Christians as pivotal in its development. From its inception, Chavittunadakam showcased an inherent adaptability, seamlessly weaving together Western theatrical techniques, Eastern rhythmic patterns, and indigenous storytelling traditions.

Arrival of Christianity

Kerala has a rich history of Christianity, dating back to St. Thomas’ arrival in 52 AD. Early St. Thomas Christians enjoyed rights and privileges. Still, Portuguese arrival in the 16th century led to changes like the Goa Inquisition, Latinisations, and a Latin bishop, causing disruptions in indigenous Christian traditions and leading to resistance and division within the community. St. Francis Xavier’s visits to Kerala in 1544 and 1549 yielded conversions among various fishing castes, including the Mukkuvas and Arayans, who adhered to Roman papal authority and Latin rites. Importantly, these castes were deeply entrenched in the caste system, and newly converted members were initially prohibited from worshipping alongside St. Thomas Christians until as late as 1914.

The Origin of Chavittunadakam

Chavittunadakam, the Kerala-based theatrical tradition, has a complex origin, with some scholars arguing it was influenced by local Christians who were exposed to Portuguese theatrical styles. Others believe the Portuguese themselves shaped Chavittunadakam by creating a Christian-themed form that aligned with their religious beliefs and cultural values. The art form is a fusion of cultural influences, including indigenous performance arts like Kathakali and Kalarippayattu.

“Initially, it was used to spread religion.”- Josy, Chavittunadakam writer, director, and performer, 2023

The Koonan Kurishu Connection

In the 17th century, Mattancherry experienced a cultural convergence, with people gathering around the Kunankurishu Church for Sunday religious activities. Tamil Catholic scholar Chinnathambi Pilla observed these practices and created a play called Brasia. The lore suggests that when he sang, a cross in the Mattancherry Church bent towards him, forming the first Chuvadi, the recital of the text of Chavittunadakam.

This cross, known as the Koonan Kurishu or slanted cross, played a significant role in the history of Christianity in India. It is believed to be the cross used by St. Thomas Christians to denounce the Portuguese kingdom in 1653, where thousands of people held a rope tied to the cross and took the oath.

The Portuguese questioned Pilla’s motivations for fostering a Christian theatre tradition, Chavittunadakam, especially due to concerns about the influence of Hindu cultural elements. Pilla’s efforts may have been driven by a desire to promote Christianity and introduce art forms aligned with Christian beliefs near Christian worship sites.

The Ashan

The ashan, also known as annave, is the master and director of Chavittunadakam. Chavittunadakam actors undergo a year-long rigorous training process at a Kalari, involving Kalaripayattu steps, dance mudras, and memorising the drama. The art form features rhythmic stamping, musical instruments, and costumes. Casting decisions are made with the ashan at the end of one year or so, but this method has dwindled over time, with shorter practice sessions now.

"In our native place, an ashan used to come and give training to young children. I started performing when I was eight years old. That was in 1976. My very first performance was two days long. It is only now that it has been reduced to the duration of a few hours.”- Treasa, a female performer, Kreupasanam troupe, 2023

The Songs

The songs are composed in the vast and varied tunes of Tamil musical literature, which Kerala has inherited from the Sangham poems. The composers of Chavittunadakam plays use various rasas, which suit the sentiment of valour and parade deeds of bravery and thrilling fights.

“Chavittunadakam is the only art form where the performers sing without backup singers. Chavittunadakam songs are usually in certain ragas from classical music. I make sure that the lines of the songs, even if it is a contemporary play, fit into the traditional ragas. Only then will it sound authentic. If you write a song like any other song, or if the situation does not match the artform itself, it won’t look complete or genuine.”- Josy, Chavittunadakam writer, director, and performer, 2023

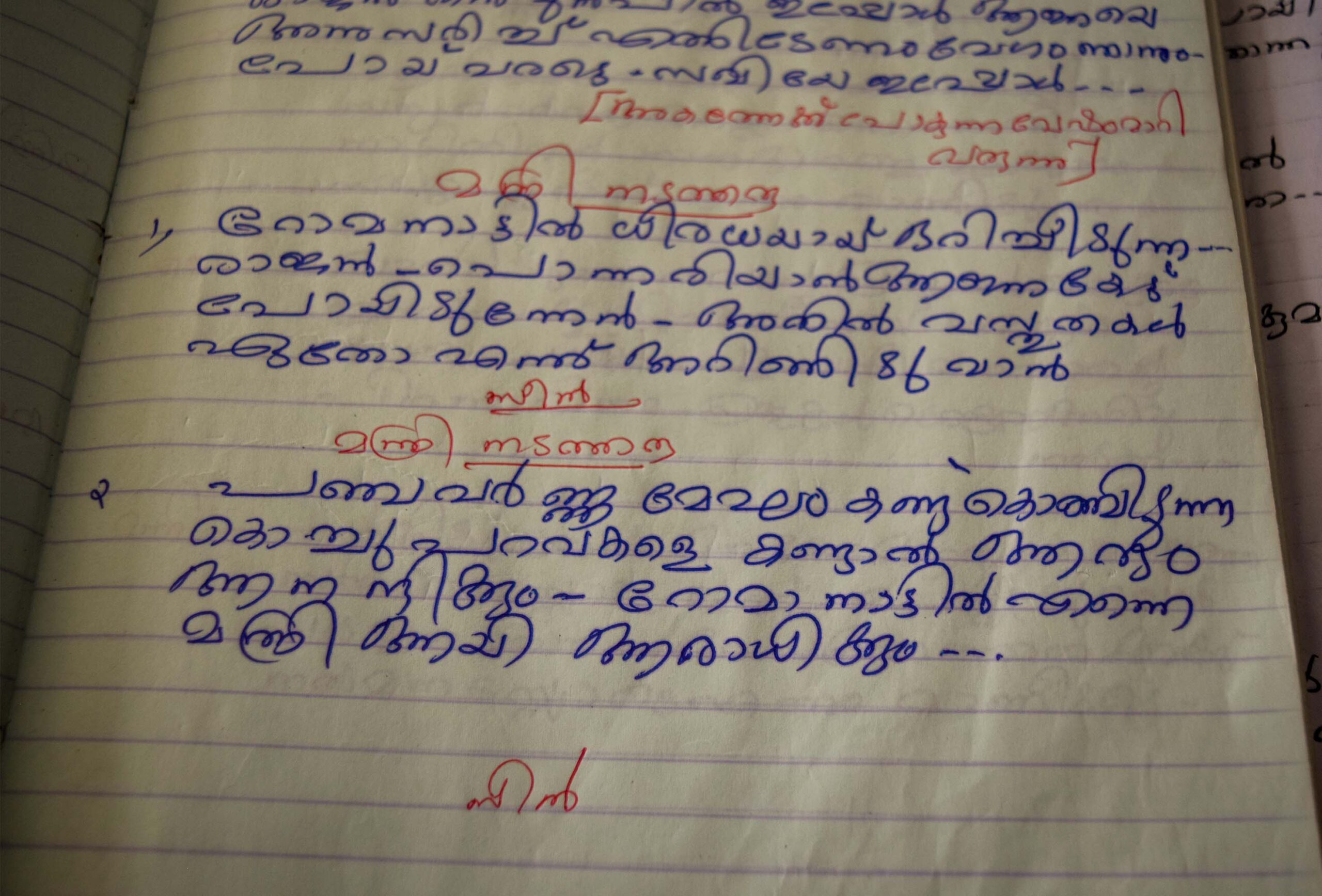

Chuvadi or Script

The ashan is responsible for the Chuvadi book, which contains the script. Chavittunadakam's preliminary prayer, 'venpa', shares ritualistic elements with Sanskrit plays. Kattiyakkaran (or clown) in Chavittunadakam, resembling Tamil and Telugu theatrical characters, suggests cultural interaction between Kerala and neighbouring regions. The selection of principal performers from Kalarippayattu provides a blend of performing arts and physical training but raises concerns about exclusivity and accessibility, potentially limiting participation of artists not familiar with the art form.

"There are various mudras in Chavittunadam similar to what one sees in Kathakali. These mudras are very important for storytelling. I have been on stage for so long that the mudras come naturally to me when I hear a song.”- Thomas, Chavittunadakam performer, 2023.

Make-up and Dress

The costumes, ornaments, and make-up convey the plot’s mood and the characters’ background. The costumes feature elaborate designs of emperors, medieval kings, and knights. Soldiers wear Greco-Roman uniforms, with helmets and breastplates modelled in clay.

“When I started performing at 14 years, in 1969, we didn't have gowns. Back then, we used sarees wrapped around ourselves in a particular style. Only men had specially-made costumes. It has only been a few years since female performers started using modern gowns on stage.”- Uma Devi, Chavittunadakam performer, 2023.

Themes

Chavittunadakam literature consists of narratives involving real and fictional characters. Initially created to instil Christian values, it evolved, allowing individuals from diverse religious backgrounds to participate. Often viewed as inferior within various sects within the Catholic Church, this discrimination is deeply rooted in societal caste hierarchy. Chavittunadakam failed to gain recognition within the realm of ‘Classical Indian’ dance forms for an extended period. This art form persisted despite minimal financial support, preserving the cultural heritage of the fisherfolk communities for centuries. Contemporary performances feature themes from Shakespeare, Oedipus, and Swamy Ayyappan, bringing the art form back to temple precincts.

“I had seen a Chavittunadakam long ago during a church festival. I have not seen any that adapt contemporary stories like we saw today. I didn't know that was done. Usually, such art forms stick to their original stories, right? This was refreshing and such a change to witness.” - Girija, audience member, Chavittunadakam performance of Jayakkodi, Kerala Museum, 2023

Moving with the Times

The inclusion of women in Chavithunatakam performances from the 1950s is a positive step towards inclusivity and gender equality, enhancing the art's relevance in a changing society. The transition from traditional heroic tales to addressing contemporary issues, such as climate change and socio-economic problems, is indicative of the art form's proactive nature in addressing pertinent concerns. The reduction in performance duration, from days to a few hours, and the alterations made to older plays to resonate with modern sensibilities further underscore Chavithunatakam's flexibility and willingness to evolve while remaining rooted in tradition. Simplifying the language to make it more accessible to a broader Malayalee audience has ensured that Chavithunatakam remains a vibrant and living art form that can engage and resonate with contemporary viewers.

“Everyone in my family was a Chavittunadakam performer. My parents, and elder sisters, all performed Chavittunadakam." - Treasa, a female performer, Kreupasanam troupe, 2023