Parallel and Tutorial Colleges: Kerala’s Alternatives for Higher Education

Non formal colleges have had more students than regular colleges since the 1970s

Tutorial colleges (tutorials) offer supplementary teaching to students from primary to higher educational levels. The earliest tutorial institutions started in the 1930s. Here, classes are held early mornings, evenings, and during vacations outside regular college hours. Besides subject teaching, these institutions provide coaching, career counselling, and guidance to students.

However, coaching centres offer specialised training or coaching aimed at specific examinations like proficiency testing or entrance exams for professional subjects or careers.

The tutorial college was started by M.P. Paul in 1932

“He started it to put food on the table when he lost his job at St. Thomas College, Trichur (Thrissur). His disagreement with the college’s principal and the Bishop led to his dismissal from the college,” said Baby Joseph, M.P. Paul’s daughter.

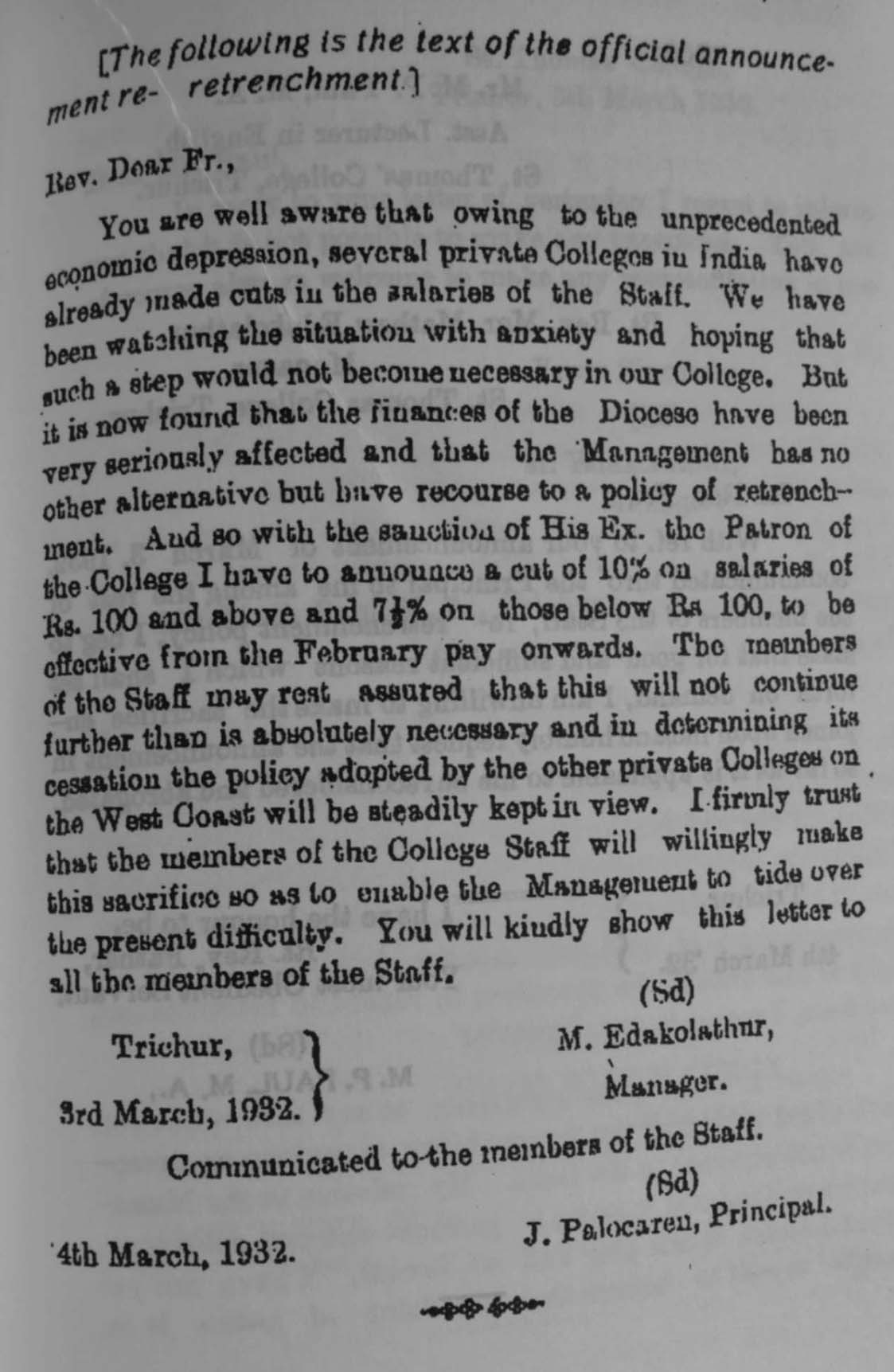

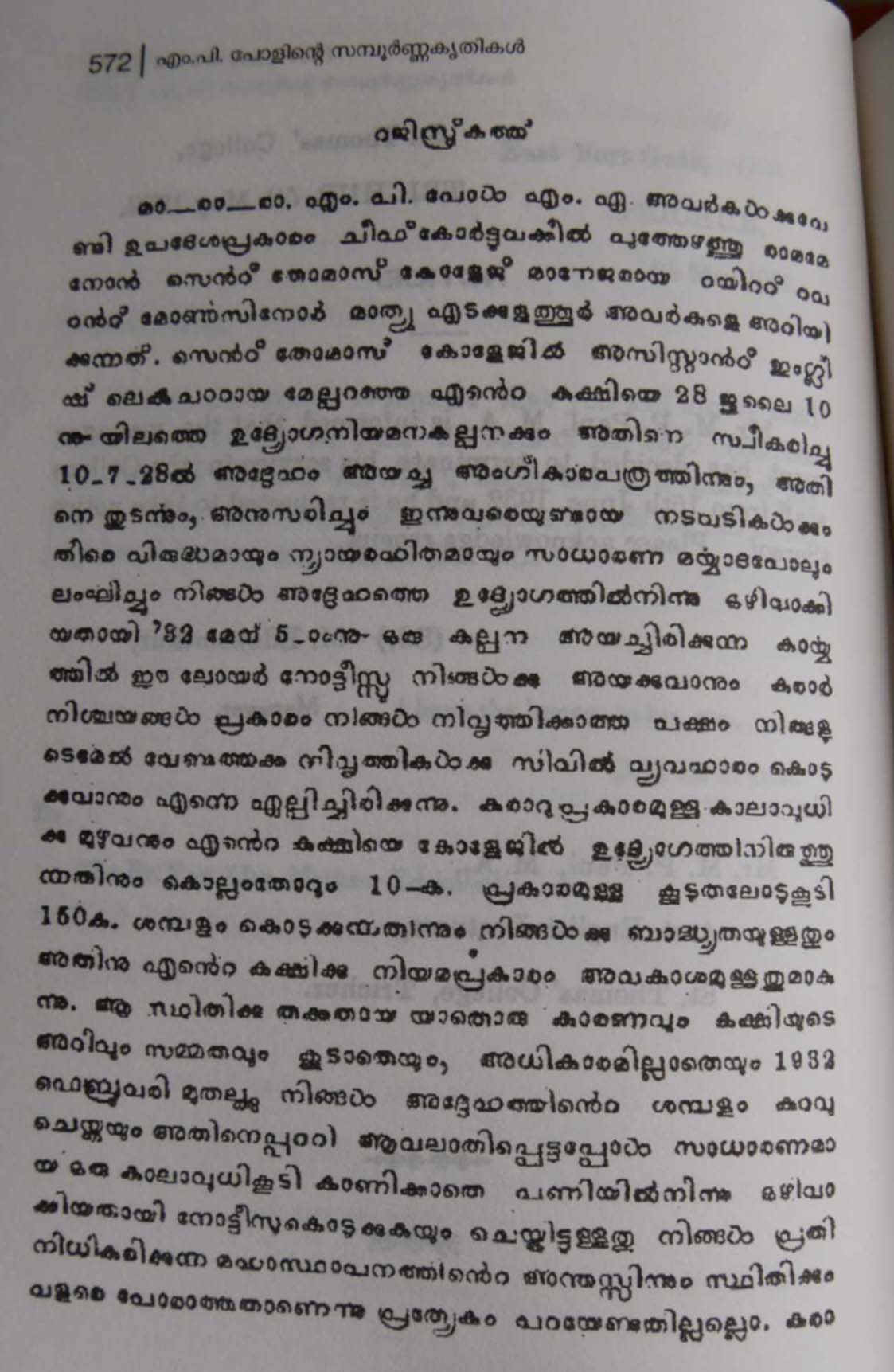

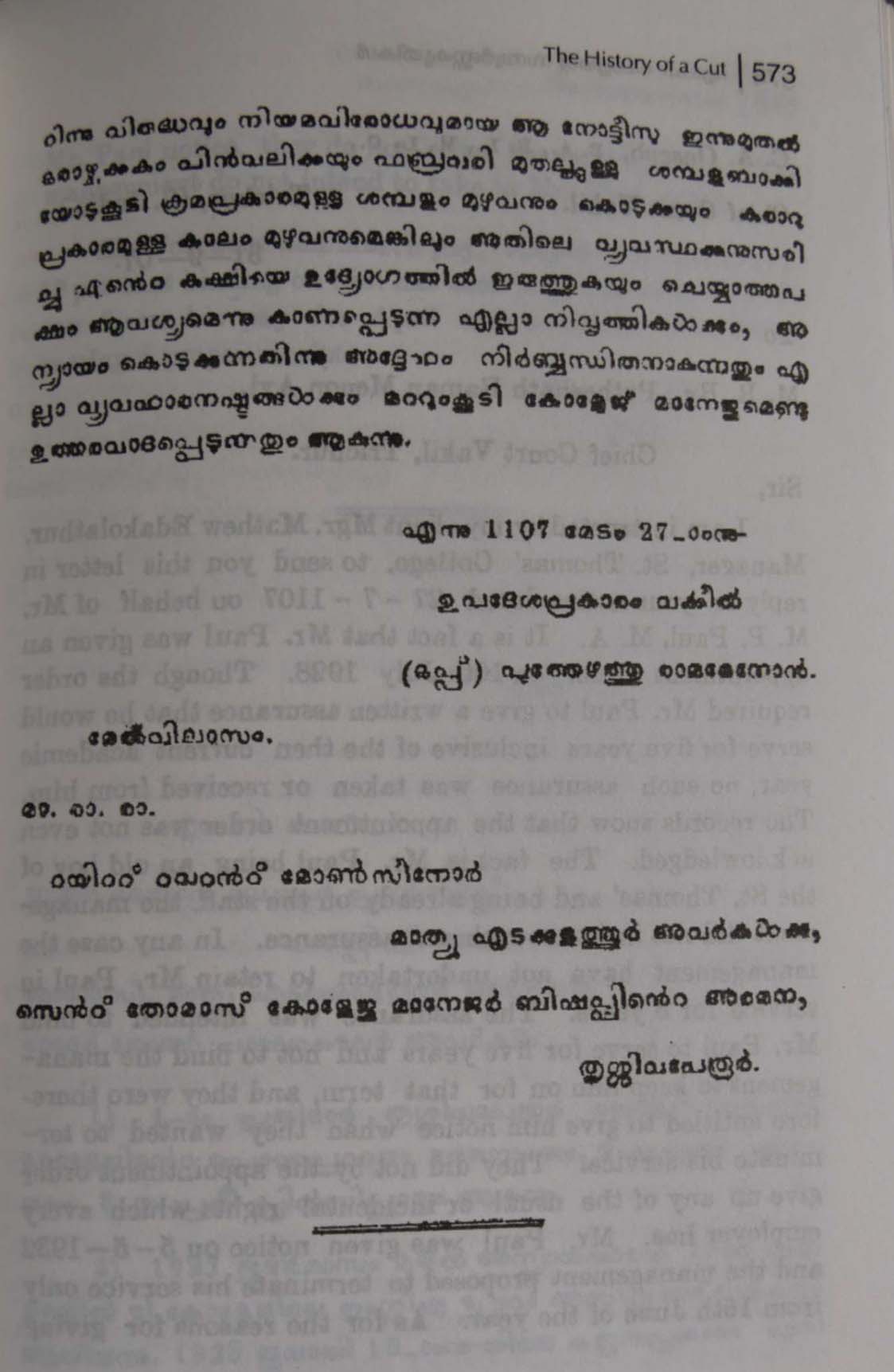

In March 1932, the college management cut the teachers’ salaries in response to a financial crisis. Paul and a few other teachers protested against this as their salaries were already low and just about covered living expenses. However, the college fees remained the same, and the financial difficulties did not affect the college. M.P. Paul filed a case against the college management and the Bishop of Thrissur in 1932. The Church agreed to pay arrears without interest to avoid a scandal, and his dismissal was changed to resignation.

M.P. Paul then rented a large house from the Kadathunadu Raja to run the first tutorial college opposite the Bishop’s House. Many of the young writers of the time met at the college in the evening. The tutorial college also served as a meeting place for the progressive thinkers of the time.

Taking on the Catholic Church

M.P. Paul was a Catholic. Taking on Catholic Church and College management in a legal battle, including the Bishop of Thrissur, was unprecedented. Baby Joseph, his daughter, remembered that their mother used to be scared for his life when he went walking alone at night or in the early morning. He had received death threats.

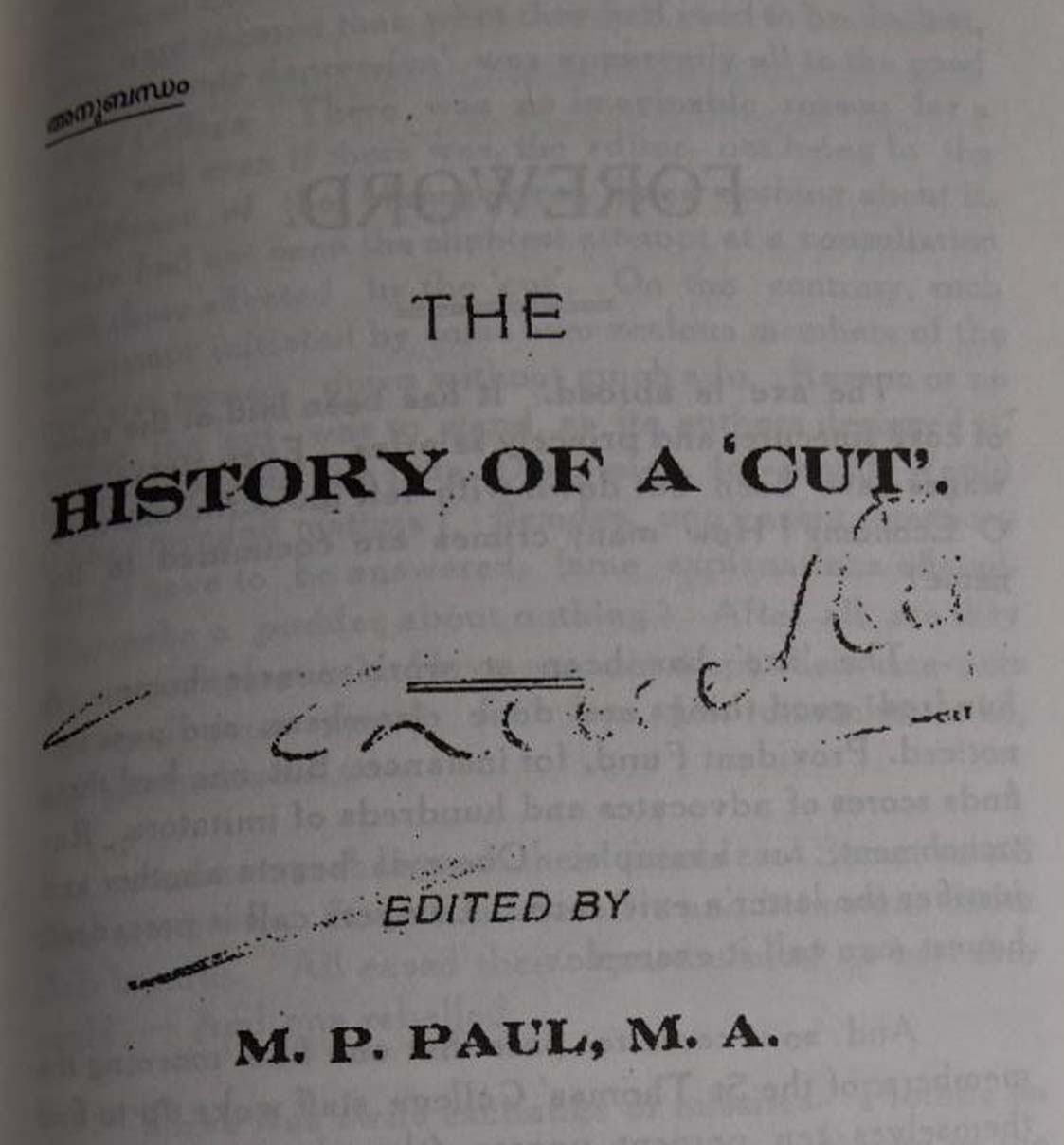

There were so many stories about the incident that Paul wrote a short essay. He published it with copies of his joining letter, correspondence between him and the college authorities, and the legal documents on the case, calling it “The History of a Cut”.

The Thrissur incident is repeated at Changanassery

In 1934, St. Berchman’s College (SB College), Changanassery, received permission to start degree classes, provided a postgraduate teacher was appointed. The then-principal invited M.P. Paul to join. By 1936, other postgraduate teachers had joined. So, when Paul had differences of opinion with the newly appointed principal, he was asked to leave SB College. Though he had a five-year contract with the college, he was dismissed, leading to him filing a case against the management.

He had difficulty finding a lawyer to fight against the Catholic college and the local Bishop again. “Adv. M.N. Govindhan Nair (father of filmmaker G. Aravindan) agreed to take on the establishment,” said Baby Joseph. Simultaneously, Paul started the M.P. Paul’s (Tutorial) College in Changanassery.

From Changanassery to Thiruvananthapuram

Paul moved the M.P. Paul’s (Tutorial) College at Changanassery to Kottayam since he would get more students there. He started another college in Ernakulam. By the 1940s, there was a feeling that the World War may come to Cochin. When people began leaving Ernakulam, Paul decided not to continue in Ernakulam and remained in Kottayam.

In 1949, M.P. Paul was invited to head the English department at the newly opened Mar Ivanios College, Thiruvananthapuram. The college used his name to advertise their teaching team, which they used to persuade him. He liked Thiruvananthapuram, and finding more opportunities in the educational world there, he moved his family to the city.

A building behind Palayam Church on Nandavanam Road was rented to start another M.P. Paul’s College branch. The family used the ground floor, while halls on the first and second floors became classrooms to teach students. Each class used to have 100 to 150 students.

George Onakkoor mentions in his book that M.P. Paul made more money through the tutorials than he had taught in a regular college. “He gave more salary to the teachers than a regular college. He would pay the salary on time for all the 12 months. He showed how a model educational institution should be run.”

Initiating a Literary Salon at Kottayam

Earlier, at Kottayam in 1945, M.P. Paul was instrumental in initiating the Sahithya Pravarthaka Sahakarana Sangham, a cooperative society of writers. The society met frequently; the meeting venue was often Paul’s tutorial colleges or his home.

“Many gained recognition through these meetings. It led to the progress of the literary field. I believe, more than a writer, he was a kingmaker of writers,” said Rosy Thomas, his daughter and writer.

The early writers were a close-knit group. They were all aware of Paul’s success with tutorials, and he encouraged them to use them. Many of them, including Joseph Mundassery, who taught in St. Thomas College, Thrissur, and later became the Education minister of Kerala, had started tutorials.

Higher Education in a 'Free' Market

The emergence of non-formal higher education resulted from excess demand for higher education over available regular college seats. Together with the availability of private registration for university examinations in the 1970s, there were more than 10,000 parallel and tutorial institutions by the end of the decade.

Parallel colleges offered regular coaching to students privately registered with universities. Many tutorials function as tutorial-cum-parallel colleges. These institutions did not need permission and were not under any governmental supervision in the early years.

However, the number of colleges increased exponentially as they filled a gap untouched by formal educational institutions. This growth in colleges and student enrollment created problems in maintaining academic efficiency.

“In the countryside, parallel colleges had a bad name. But in Thiruvananthapuram, they were run pretty well. It was a city, so people didn’t mind studying in these colleges here,” said Sreekumar K., a teacher at Our College.

L. Gopikrishnan, who has coached students for various entrance examinations, said with quiet pride, “At least 100 students I taught have passed the MBBS entrance and become doctors now.” However, many other parallel-cum-tutorial colleges could not or did not maintain the quality of their teaching.

Non Formal Higher Education in Kerala

Demand for higher education grew rapidly in India in the 1970s. The factors that led to this were (a) a growing number of jobs that needed higher education degrees, (b) people without higher education had to wait longer to find a job, and (c) people’s socio-economic aspirations were moving up.

“The educated youth in Kerala were going through a period of unemployment, which resulted in unrest. Many, including me, were attracted to Naxalism because of this. The government took strong steps to check the Naxalite movement, and many people with an affinity towards Naxalism started tutorials to counter unemployment. Parallel colleges provided employment and took them away from the Naxalite movement,” said L. Gopikrishnan, a parallel college teacher who taught both botany and zoology in tutorial classes and coaching for the entrance examinations (NEET).

Principal Olivil: Ente Ormakal, Anubhavangal

Viswabharathy had around 3000 students when L. Gopikrishnan was teaching there. Velappan Nair started it for students who had failed the Standard 10 exam. All the teachers were schoolteachers.

Government-employed schoolteachers were prohibited from teaching in private institutions; therefore, there were checks by the vigilance department in many places. Often, government teachers had to sneak in and out of the parallel college. Gopikrishnan directed a movie based on this theme in 1985 called Principal Olivil (Principal in Hiding). Later, he wrote a book about his experience making the movie Principal Olivil: Ente Ormakal, Anubhavangal (Memories and Experiences).

Our College

“The college was started as an alternative educational institution. Initially, students were given tuition in subjects they wanted to learn. Later, the institutions were raised to the standard of a parallel college. We still have laboratories and equipment for physics, chemistry, and biology,” said Sreekumar K., who has worked with the founder.

K. Balakrishnan Nair founded Our College in 1952 at Pattom Thiruvananthapuram, a few years after M.P. Paul’s College was established in the city. Balakrishnan Nair was studying for his BSc degree when he began his tutorial service. He helped school students from the nearby school with English, Mathematics, and Science subjects. The following year, he opened another tutorial branch in his hometown, Aryanad. The students at Aryanad gave the name “Our Tutorial College” to the institution. The Pattom branch was subsequently called “Our College”.

Our College, one of the largest parallel colleges in Kerala in the late 1970s, had 8000 students on its rolls in the 1980–90s period. It has various branches, including those in Thiruvananthapuram and Ernakulam.

Teaching Practices at Tutorial and Parallel Colleges

Baby Joseph, M.P. Paul’s daughter, remembers her father asking her to attend the English tutorials at his college before her university examinations. “Classes were started for students who failed in English. BA English students joined at first. Later, the college expanded to include students who had failed in science subjects or wanted extra coaching,” she adds.

Sreekumar, a teacher at Our College, said, “We have regular tuition for Plus Two courses and degree courses. The students would be enrolled in a college and join Our College for extra classes. We provide short-term, medium-term, and long-term coaching courses for medical and engineering entrance, beginning in high school.”

These colleges also helped regular college students who needed extra support that formal educational structures could not provide. The good parallel colleges had systems similar to or better than regular colleges to track students’ performance. Colleges were competing with each other and needed to maintain a good reputation; they could not afford to retain teachers who did not meet the students’ expectations.

Student perceptions

“We had classes in the morning till noon or only in the afternoon. The hours were not like regular college hours at Maharanis,” mentioned Ruby Tomy, who did her MA privately at Maharanis College, Ernakulam.

“They bring in teachers from outside. These teachers were excellent. I am now doing an MSc Statistics course here at University College,” said Athira Sreekumar, former student at Our College, Thiruvananthapuram. She had joined Our College for extra-tuitions in her fourth semester of B.Sc when she found Statistics difficult. Athira also took up a few other subjects. Today, Athira has shifted from her original mathematics to do an MSc in Statistics.

According to Gopikrishnan, most of the students at Viswabharathy lived within a 10–20 km radius. The students at parallel colleges got discounted bus fares like regular students, but less than them.

Boarding Facilities from the Beginning

“Female students came from faraway places like Pala and Kanjirapally to join the tutorial colleges,” Vincent Paul mentioned. “Parents wanted them to have a secure place to stay. That was the reason behind the hostels.” The warden took care of the students’ food and other non-academic requirements.

In the mid-twentieth century, few educational institutions existed in villages and rural areas. Therefore, tutorial colleges provided boarding facilities to students. M.P. Paul ran the Tutorial in a large building at Thrissur, where his family lived on the ground floor, and some students stayed with them. Later on, M.P. Paul’s Colleges had separate hostels for the girls. “These were independent buildings or rented houses with ‘M.P. Paul’s Hostel’ name boards placed outside,” Baby Joseph, his daughter, recalls.

All branches of Our College had hostel facilities. They had a separate team to care for the hostel and the students. Most modern coaching centres have facilities for accommodating the students, especially those receiving coaching for specific examinations.

Teachers at Tutorials and Parallel Colleges

“Most of the teachers were young and inexperienced. There was just one good teacher. He was also the college’s founder,” said Ruby Tomy, a student at Maharani’s College, Ernakulam, in the early 1990s.

Generally, teachers were selected through management decisions or tests. At Our College, “A few teachers were permanent and had access to provident fund. The permanent teachers would get 2–3 days of holiday a month. Most of the teachers were on a contract basis and paid hourly. Therefore, they would not take holidays. Work was quite hectic,” Sreekumar remembered.

“At Viswabharathy, most of the teachers were male. We stayed at a lodge near the college. The teachers’ salary was high and negotiated based on their popularity,” said Gopikrishnan, a former teacher.

In tutorials and parallel colleges, the qualifications of teachers varied. In the 1970s, about a third of them had basic degrees, and less than 10% had diplomas. Many teachers use parallel colleges as stepping stones to other careers.

Currently teaching in a well-to-do coaching centre, a teacher retired from a well-known college said, “I joined the institution since my former student was teaching in the same place and told me they had openings for more teachers.” The coaching centre provides additional income and takes care of his free time while enabling him to continue his profession.

In the early days, M.P. Paul’s tutorial college was run as a family enterprise. C.J. Thomas, a teacher in Paul’s tutorial, became Paul’s oldest son-in-law. N. Gopala Menon, appointed to teach chemistry and physics at the Kottayam branch of the college, went on to become the principal. Noted writer Vaikkom Muhammed Basheer was a family friend who worked as the warden for the hostel in Ernakulam. Muttathu Varkey, another writer, used to teach at Paul’s College.

Advertising and Marketing

Rosie Thomas, the daughter of M.P. Paul, mentions that when C.J. Thomas took over M.P. Paul’s tutorial college, he acquired another struggling tutorial nearby. The staff urged him to advertise the fact, something M.P. Paul would have done. However, this advice was ignored, and Rosie writes that this led to both closures.

Parallel colleges spent heavily on advertising. They used leaflets, banners, newspaper advertisements, cinema slides and even sent agents on home visits.

“Balakrishnan Nair, the founder of Our College believed that students joined by word-of-mouth publicity. We did get a lot of students, but once other institutions started other forms of advertising, we could not keep up.” Sreekumar of Our College said. He added, “The college had issues with enrolment once other institutions in the locality started door-to-door and telephone canvassing. They would go to schools and meet the principals and students. They even obtained the telephone numbers of the guardians and would call them”.

Parallel Colleges - End Games

“When pre-degree was delinked from colleges and attached to schools such as Plus One and Two, many rural schools couldn’t offer quality education. Instead, smaller tutorials sprang up in large numbers near the schools. Students chose to enrol in these institutions,” explained Gopikrishnan, a former teacher.

Since the 1990s, the government has promoted more private participation in higher education by allowing self-financed or unaided colleges to operate. By 2012-13, self-financing colleges accounted for 58% of all colleges. Some private-aided colleges, such as Mar Ivanios, introduced self-financing courses within their premises. Students who used to rely on parallel colleges now had the option of joining the more prestigious self-financing colleges established in urban and rural areas.

In the late 2010s, universities in Kerala stopped private registrations and placed those students in the distance education program. Simultaneously, the University Grants Commission modified rules so only universities with an A+ accreditation could offer distance education programs. Hence, over one lakh students in Kerala who used to register as private candidates had to rely on universities outside the state for registration.

Sisir Kumar S.I., administration officer at Our College, Thiruvananthapuram, said, “The college could not upgrade with suitable infrastructure during the COVID pandemic. Many students who require coaching and tuition prefer to do it online. The college management was not convinced about the need for online teaching after the pandemic, and it is now affecting enrolments.”

Tutorials and the Rogue's Pit?

The story of tutorials began with M.P. Paul and the Catholic Church. After Paul’s death, the Catholic Church authorities refused to have him buried in the church cemetery or conduct the official death rites. Even his brother, Monsignor George Menacherry, was prohibited from performing the rites. Paul was entombed in a vault outside the sacred ground called chattambikuzhi (Rogue’s pit). However, over the years, when the cemetery was expanded out of necessity, his tomb ended up being located right in the middle of consecrated grounds.