On 8 March 2023, the Ernakulam district collector declared a two-day holiday for schools in and around the city of Kochi due to the fire at the Brahmapuram waste plant. For those of us who grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, our school and college years were peppered with bandhs (or hartals as they are called now) as well as long holidays for the summer vacation, Onam, and Christmas. This was in addition to Sree Narayana Guru Jayanthi, Deepavali, Eid, Muharram, Pooja holidays, and other occasions. Since the 2018 floods, schools have also started giving “rain holidays” frequently.

The official diaries of the Educational Secretary of Cochin from 1892 to 1896, found in the Regional Archives, Kochi, contained letters sent to educational officials in the Princely State of Cochin. Among these letters were ones discussing the days to be observed as holidays for educational institutions in the state. These letters offer a fascinating look into the time, culture, and physical setting of the princely state during the late nineteenth century and provide valuable insights into what the education department considered worthy of holidays.

Significance of School Holidays

What do holidays signify in the educational space? How are educational holidays decided? Holidays tell us about the weather, natural disasters, politics, historical phenomena, and other important aspects.

In nineteenth-century Cochin, holidays tell us about the region’s political power and dominant religious communities during that time. Culture and economy play a role in deciding which holidays to observe. Social movements and changing attitudes can lead to the creation of new holidays or rethink the significance of existing ones.

National Holidays

Why were national holidays important? National holidays reflect historical events or important milestones in a nation’s history. These events are larger than local events, places, and people. They provide a shared sense of identity and unity among citizens.

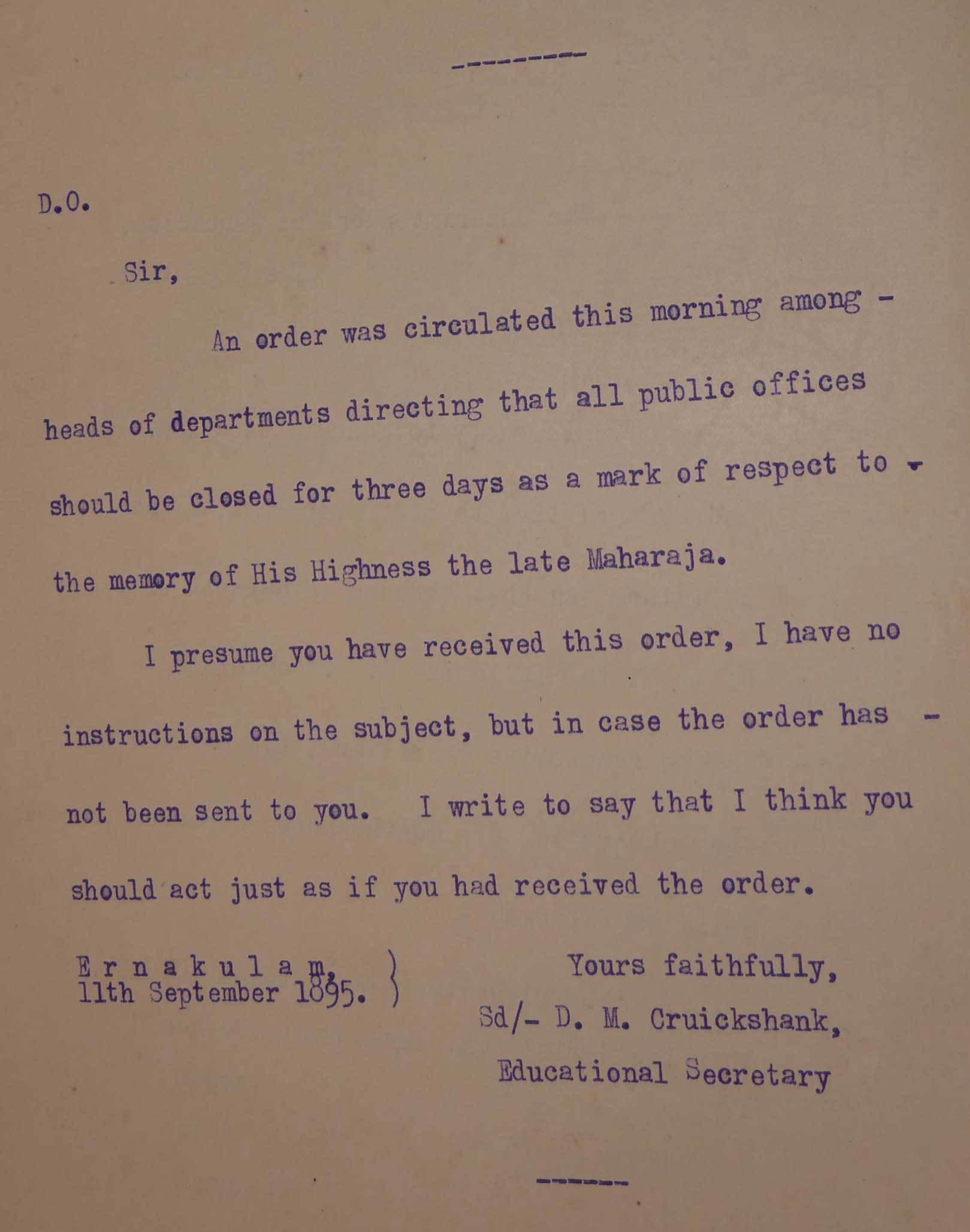

For instance, from 1888 to 1895, Raja Veera Kerala Varma was the Maharaja of Cochin. On the demise of the reigning monarch, all public offices were given a three-day holiday, as can be seen from the letter written by the Educational Secretary on 11 September 1895.

National and State Events Leading to Holidays

Independence Day, Republic Day, and Gandhi Jayanthi are national holidays. Many students attend schools and colleges for the flag hoisting ceremony even though it is a holiday. From the monarchy, nationalist or patriotic sentiments have shifted to the nation of India.

Kripa S., 39, a software engineer from Eloor, remembered, “We used to get sweet packets from the school for days like Independence Day and Republic Day. We exchanged sweets we liked for those we didn’t amongst ourselves. It was great fun.”

It is common to get holidays when politicians or eminent personalities pass away.

Thresiamma V. Sankoorikal, 72, retired teacher and headmistress, said, “Whenever a minister died, we would get that day as a holiday in school and college. It is only recently that it has not been so.”

Christmas in Princely State of Cochin

The Resident (The highest British official posted in the capital of princely states, who was a diplomat but with considerable power in state governance) and many of the officials were British. There were a large number of native Christians in the population. A part of Cochin was under British rule, called British Cochin (now Fort Kochi). Because of all these, Christmas was an important holiday, with institutions being given holidays for up to a month in British India and England.

Christmas holidays in post-independent India

In Kerala, Christmas was always a school and college holiday. However, that was not the case in other locations in India post-Independence. Arun Kumar, 60, a non-resident Malayali engineer who did his schooling in Kolar Gold Fields, reminisced, “For us, the school holidays were different. The big holidays were the summer vacation and the Dussehra holidays, not Christmas.”

Holidays and History

People’s recollections of holidays bring to life the forgotten history of the state. For instance, the Island Express on the Bangalore—Kanyakumari route is one of the oldest trains. During the summer vacations in the early 1970s, Arun Kumar, 60, always travelled with his family from Kolar to Kottayam. They would come down in the Island Express and get down at Ernakulam. “The train’s last stop was Wellington Island in Kochi, which was why it was called the Island Express,” said Arun.

In those days, most trips were done by train. The berths in the sleeper coaches were not cushioned and were made of hardwood. Travellers used to carry thin mattresses within a hold-all made of canvas. Each person would take a mattress and use it. The entire hold-all would be used like a sleeping bag if it were a single person. “Looking out continuously, getting covered in charcoal smoke, it was all an experience in itself.”

Island Express: A Short History

The train was started in the 1960s and was called the “25/26 Cochin – Bangalore – Cochin Island Express.” Before that, just 3-4 slip coaches were attached to the Cochin-Madras Express, which started from the Cochin Harbour Terminus. The slip coaches were detached at Jolarpettai and connected to the Bangalore Mail, which would take them to Bangalore. The Cochin Harbour Terminus was the last station of the Island Express till the mid-1970s. In 1976, the Kottayam-Thiruvananthapuram route was converted to broad gauge. The train was extended to Thiruvananthapuram, and later, it was extended to Nagercoil and then to Kanyakumari. The train was also renamed 16525/16526 Kanyakumari-Bangalore Island Express.

Summer Holidays and Malayalis

Summer vacation was when many Malayalis travelled to their ancestral homes. Children of working parents were left with their grandparents during this long holiday. Kripa S., 39, recalled fondly, “My grandmother would take me to the temple daily in the morning. On the way, we would meet many acquaintances. They would all shower affection on me in the typical fashion of rural people”. For Kripa, the countryside was a place of warmth, fun, and leisure.

Some families would travel to places like Wagamon, Kumarakom, Kovalam, and Munnar, i.e., hill stations, backwaters, beaches, heritage sites, or locations outside Kerala/India. These were the propertied classes, non-resident Keralites, or the newly emerging business-class families. Thus, where a family spend their holidays also shows their class/caste position in society.

Children who lived in their ancestral homes, the tharavads, did not travel much during festivals and vacations. Vineeth K.’s, 39, narrative on growing up in Eloor had all the quintessential ingredients of the idyllic summer vacation. His childhood home was surrounded by large tracts of cultivated land, interspersed with abandoned houses, smaller farmhouses, wastelands, a sacred grove, and a cemetery. He was allowed to roam wherever he pleased, and he also explored areas that were forbidden, like the cemetery and the sacred grove. He spent his summer vacations at home, “waiting for the various relatives and neighbours to arrive.” For, “the games were different then.”

Subaltern Narratives of Holidays

Not everyone travelled during the summer vacation. While holidays generally positively affect well-being, some individuals may also feel stress or loneliness, particularly if they lack social support or face financial constraints during holiday periods. Kumari, 62, Thrippunithura, who works as a housemaid, said they did not have the means to travel anywhere. They spent all their school holidays at home. In the case of Kumari, she was very reticent about describing her holiday activities because it appeared as if she was reliving her difficult childhood.

Organised Summer Vacation

Over the years, Malayali kids came to be enrolled in summer camps and activities. Anoop K., 43, a software engineer, remembered that in one era, it used to be typewriting for teenage boys and sewing, machine stitching, or typewriting for teenage girls. Later, the set of activities increased to include coaching in sports, arts and crafts, and so forth. As time passed, younger children began to be enrolled in these activities. Various schools, clubs, and residential groups would hold performative activities to engage the children.

Holiday celebrations often involve communal activities, such as shared meals or engaging in cultural traditions that promote social integration and solidarity. The collective experiences facilitate the formation of positive memories and shared narratives, contributing to a sense of collective identity.

Summer Vacation in Cochin

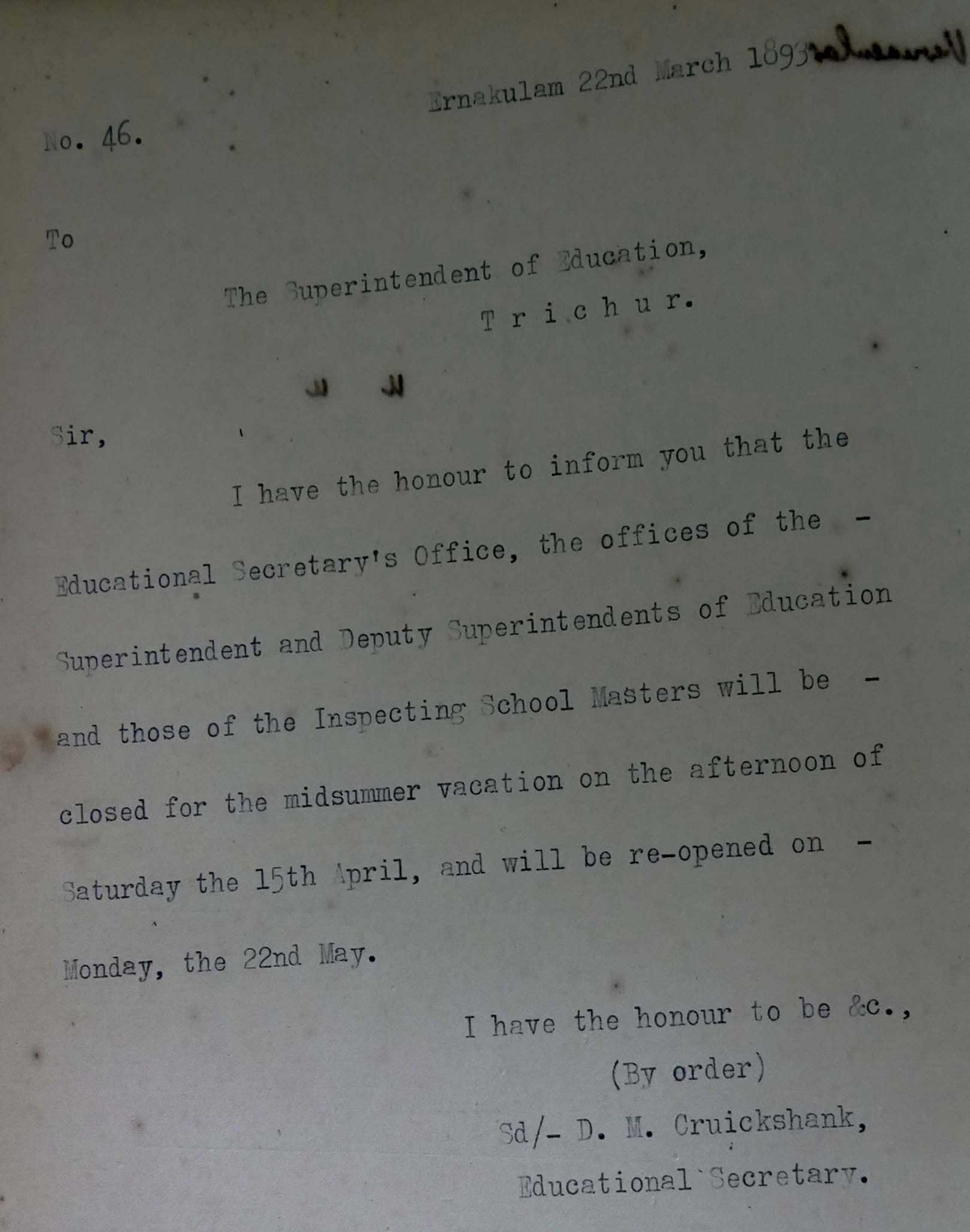

Midsummer vacation for educational institutions, like it is today, was a prevalent practice from the nineteenth century in Cochin. There are letters in the Educational Diaries from 1892 granting permission for schools and colleges to close for summer vacation. However, whenever schools were given unexpected holidays for a longer duration, the working days lost were made up by cutting short the summer vacation (and occasionally the Christmas vacation).

Onam in Colonial Kerala

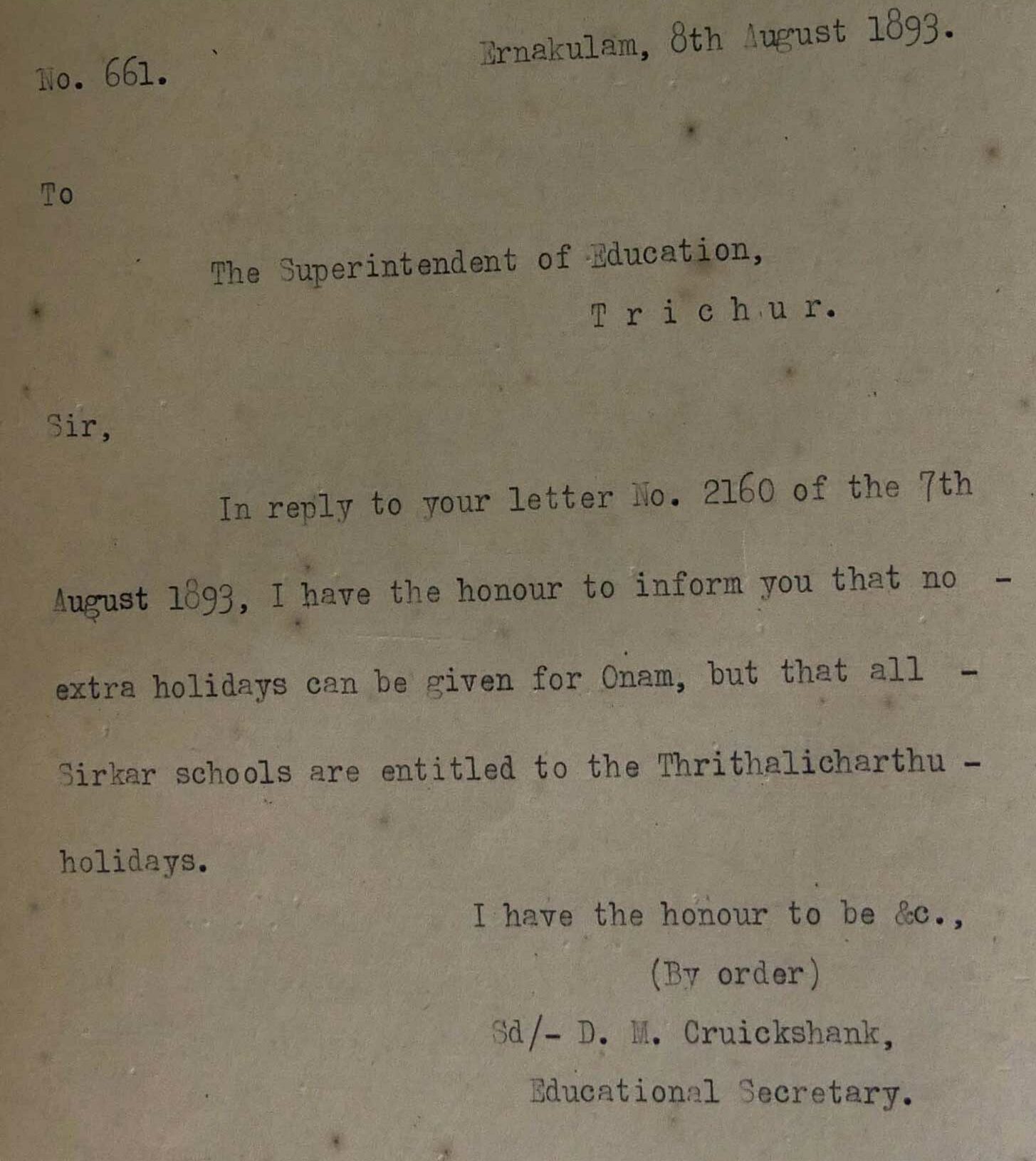

Onam was celebrated throughout Travancore, Cochin, and Malabar. Schools used to get weekly holidays during Onam in late nineteenth-century Cochin.

Onam: Today

How has the celebration of Onam changed from colonial times? The Thrikkakara Vamanamoorthy Temple, Thrikkakara, is the centre of Onam celebrations in the state. It was a ceremonial celebration connected to the temple before it became the state festival in 1961. In post-independent Kerala, Onam was one of the big educational holidays after summer vacation. In Kochi, most festival-related performances and rituals are held at Thrikkakara and Thripunithara, the seat of the erstwhile Cochin Maharajas.

Anoop, 43, recollected that the Onam celebrations that they used to have at their paternal tharavad in Thiruvananthapuram were huge affairs with food being cooked in large vats for the Sadya (traditional feast), “It was exactly how Onam was supposed to be.” Anoop remembered visiting Kowadiar to see the decorated streets. The entire city is decked up during the Onam celebration, and Kowadiar is the centre of the festivities even today.

Important State Celebrations in Cochin

While Onam was important in most of Kerala, the Educational Secretary did not always give extended holidays. In nineteenth-century Cochin, schools in Thrissur (called Trichur then) were not expected to close for an extended period for Onam. Holidays were allowed for Thrithalicharthu. Thrithalicharthu was the wedding ceremony held for the royal princesses before they reached puberty. This was a four-day long ceremony, and the groom would leave after the ceremonies. The princess would take another Namboothiri as consort once they reached adulthood. This pre-pubescent wedding ceremony was present among other Hindu communities and was called talikettukalyanam. It was a grand affair for many Hindu communities until the mid-twentieth century.

Local Festivals in Cochin

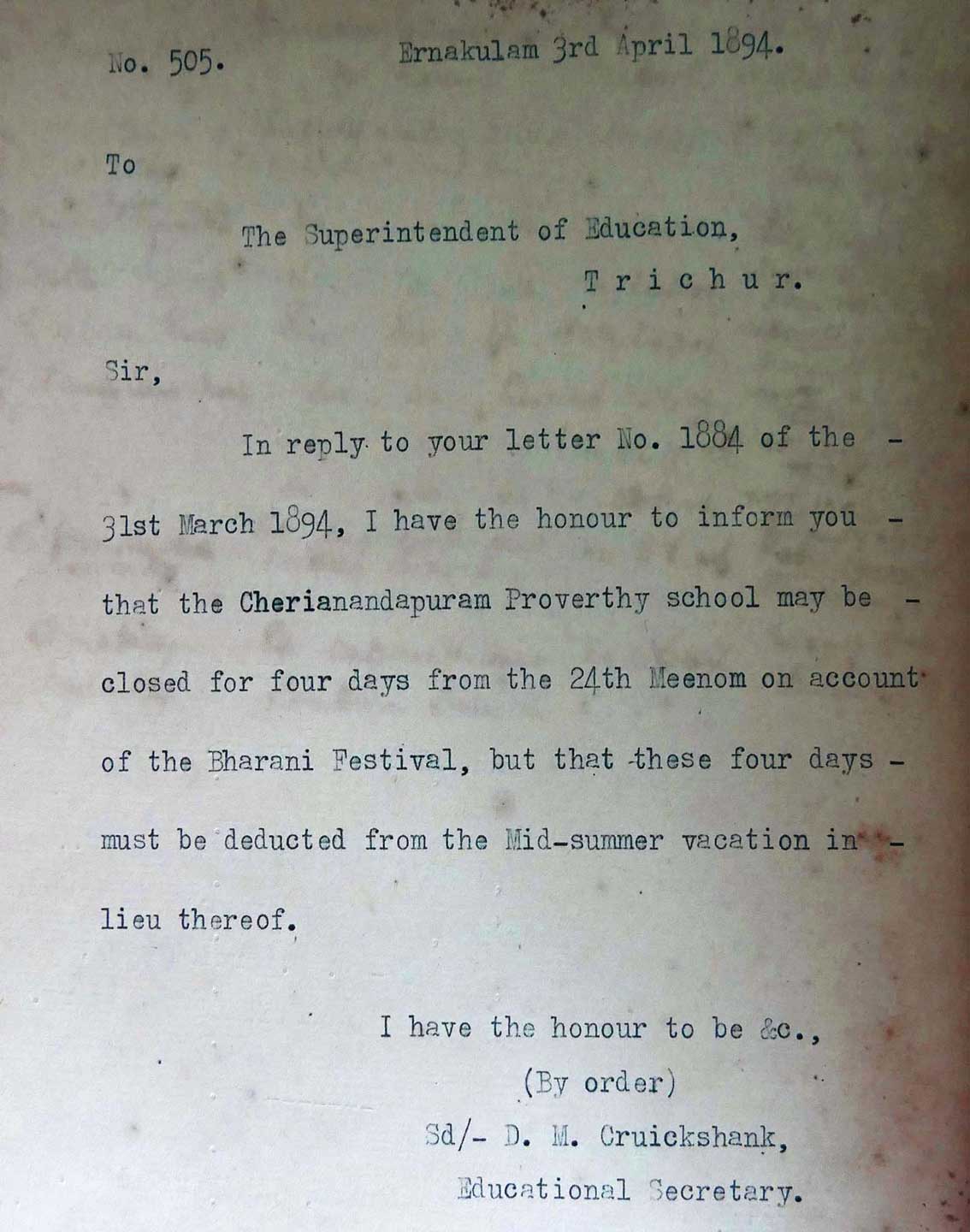

In late nineteenth-century Cochin, Bharani was another festival for which local educational institutions were given a holiday and an equal number of days was deducted from the vacation period.

Bharani

Today, Bharani is celebrated only in Thrissur district, and holidays are given only to institutions in the district. Fathima K.M., 64, from near Kodungalloor, narrated certain aspects of the Bharani from her school days, “There was a lot of noise and celebration. The people would sing, dance, and go in a procession on the road in front of my house. The road leads to the sea. They would throw money into the sea. Coins would fall on the road too, and the children rushed to pick up the money.” She was not allowed to take part in the main poojas or festivities at the temple, but the family loved to visit the temporary stalls and performances. One of her uncles had a car, and “We would all go in the car to see these,” mentioned Fathima.

COVID-19 and Educational Institutions

Schools in Kerala were closed for nearly two years, from March 2020 to May 2022. This was not a continuous shutdown. Schools had online and televised classes from June 2020. In November 2021, schools were officially permitted to open in a hybrid manner with offline and online classes. Due to the resurgence of the pandemic, they were closed and opened again in February 2022. Initially, offline classes were held only for students with board exams (Standards 10, 11, and 12) and for college students.

Megha Ram Mohan, a research intern, studied in Plus Two (Grade 12 in the Kerala State Education Board) in March 2020. She remembered that she could not write the final examination for one subject due to the initial three-week lockdown, “We were called back in April for a day to write the exam.”

“We had to attend offline class for a week in 2020. In 2021, we were called on and off to college for classes lasting a week or so. Once, we were supposed to have an offline class, but all the teachers were down with COVID-19, so that session was cancelled. Proper offline classes started in earnest in 2022. But I remember my younger school-going cousins did not have as many offline classes as we had during COVID-19,” she added.

Epidemics in the Past

Rosily Paul, 82, who grew up in Narakkal in the late 1940s and early 1950s, said there were hardly any holidays given for epidemics in her school days. During a flu epidemic, four to five people were bedridden with the disease in most of the houses in her village. But no holiday was declared. Rosily mentioned, “As far as I can remember, the situation was really bad.”

Smallpox

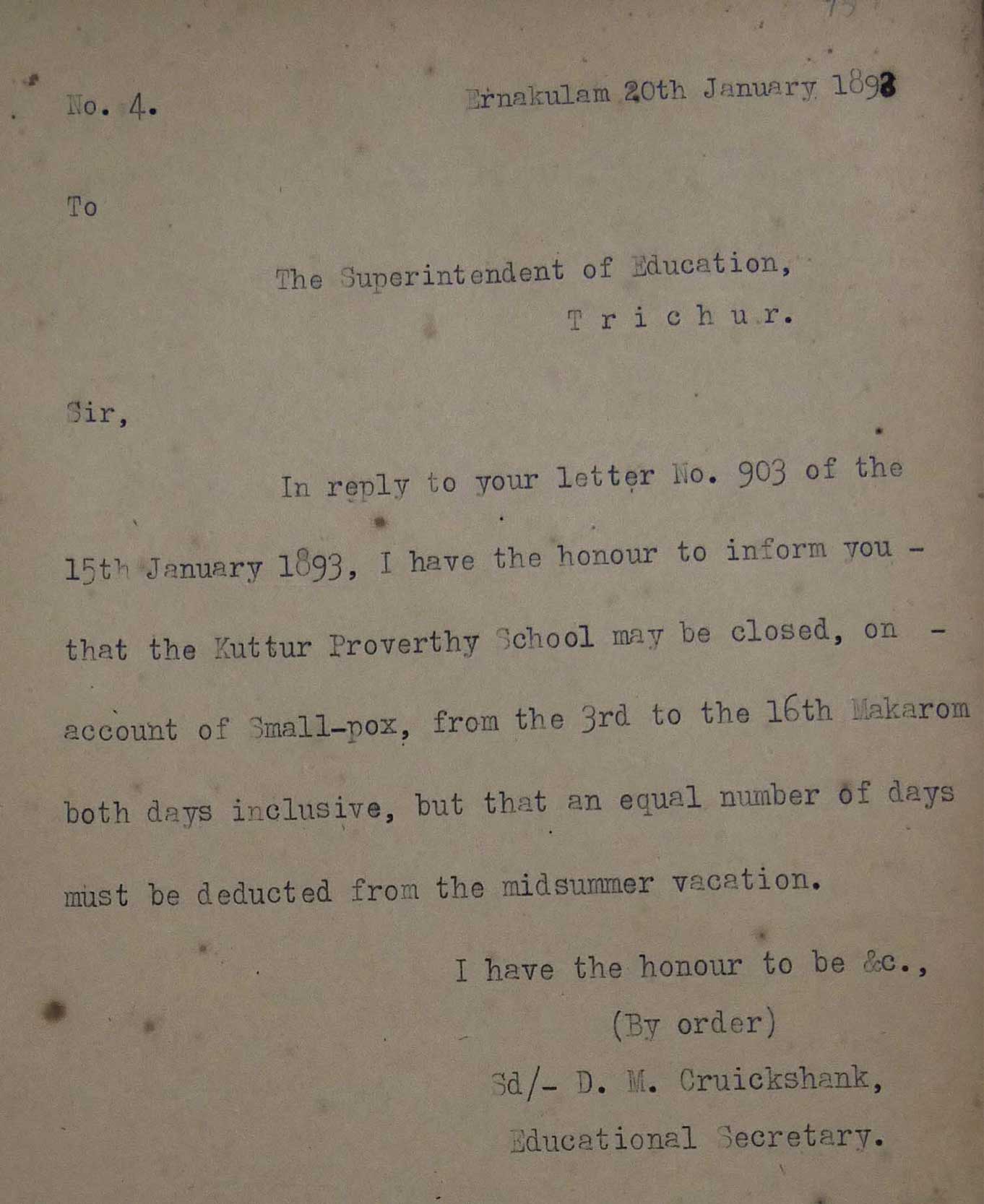

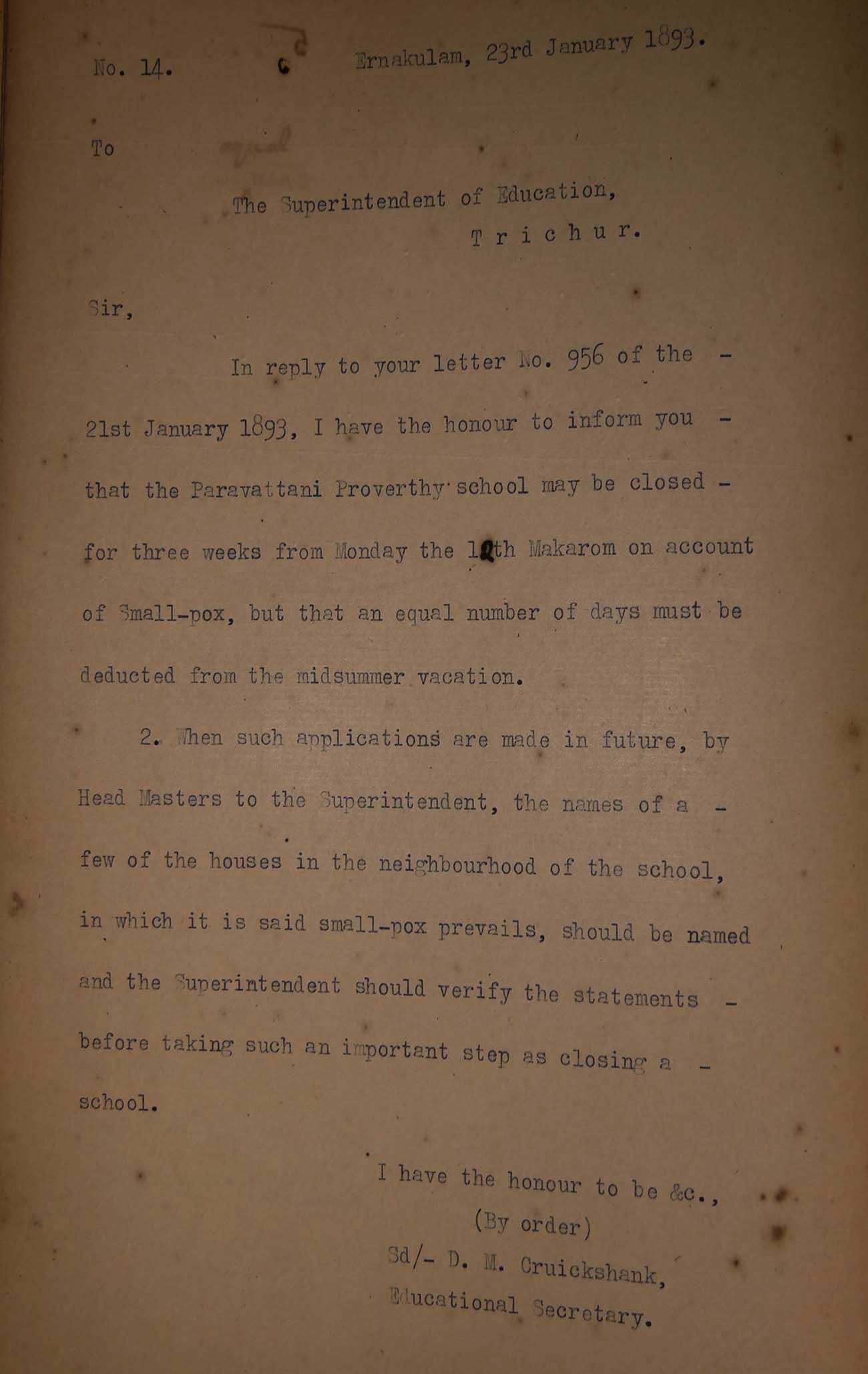

In late nineteenth-century Cochin, schools had to be closed periodically whenever the smallpox epidemic broke out in a region. The trajectory of the disease in the princely state can be traced through the schools that were being closed, their locations, and when they were being closed. For instance, in 1893, schools were closed in January and then in March in various places due to smallpox. One year later, in 1894, a few schools had to be closed due to the resurgence of the smallpox epidemic.

Verification of Smallpox

Did schools get holidays every time a smallpox case was reported in the area? Schools were given holidays for smallpox after the cases were confirmed. In 1893, the Educational Secretary asked the Superintendent to furnish details of a few families in the vicinity of the school affected by smallpox and verify the information. Since there are no other details given with the letters, it could be inferred that either the schools were asking to be closed due to a mass panic situation or the administration had reason to believe that some school authorities were giving false information regarding smallpox cases in their vicinity.

Cholera: Another epidemic in Cochin

Cholera was a major epidemic in Kerala until potable water became available. Schools were frequently closed when a region was affected by this epidemic. In 1894, both Mattanchery and Trichur had school closures due to cholera.

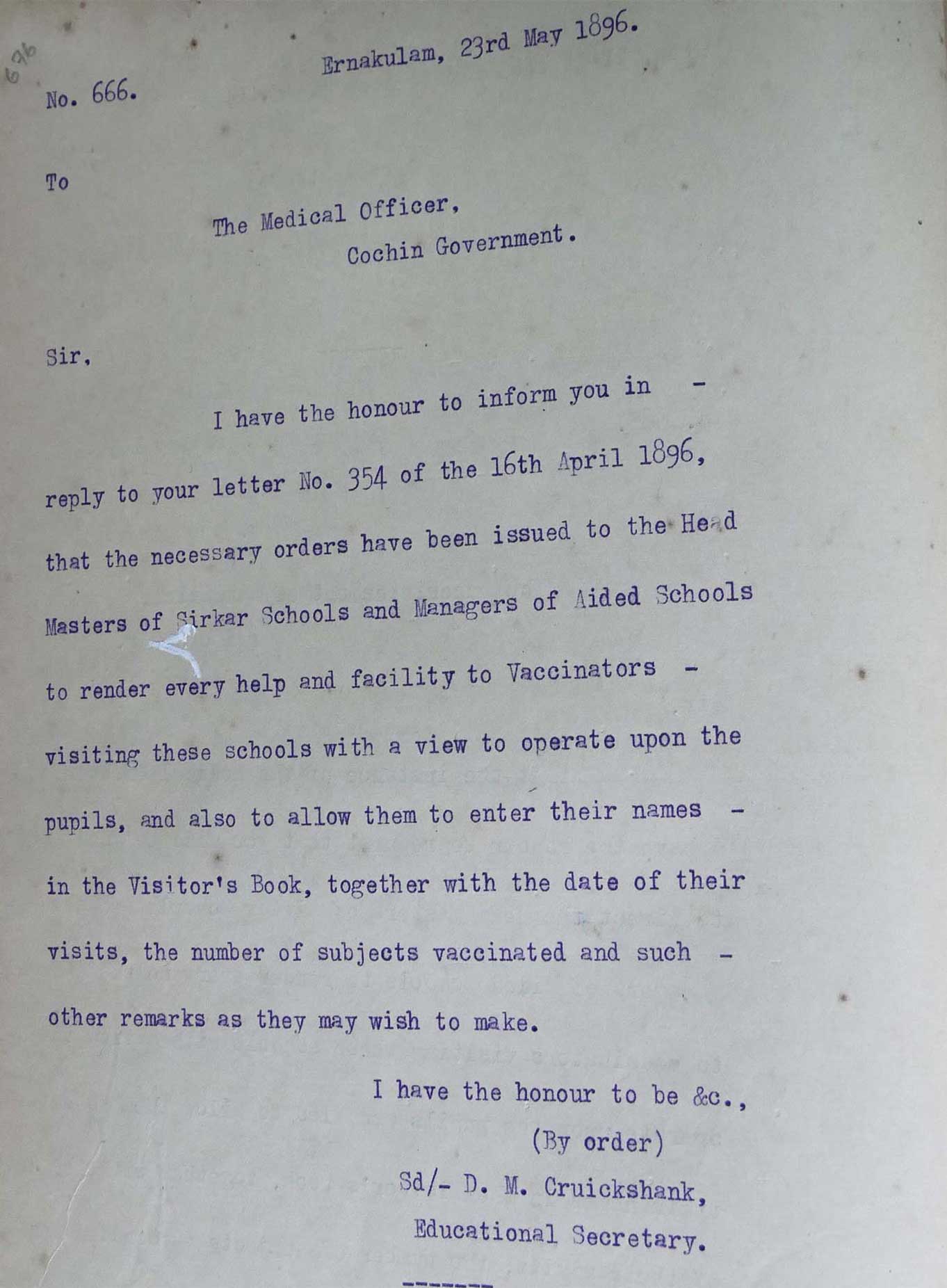

Smallpox Vaccination

The government and educational authorities made the necessary arrangements to vaccinate both school (government and aided) and college students. In March 1896, the Diwan informed the Ernakulam College (Maharaja’s College) principal that the medical officer had been requested to send a vaccinator to the college. The schools were provided with vaccinators in May.

COVID-19 Vaccination

During COVID-19, schools and colleges in Kerala were offering vaccination for students who were not vaccinated. The COVID-19 vaccination was made available to students between the age groups of 15 to 17 from January 2022. Those above 18 years had access to the vaccination before this. Vaccination drives were also held in schools once the children’s vaccination became available.

Advait Arjun, 15, a student from Kochi, got the anti-COVID vaccine in early 2022. He was taken to a nearby hospital and got the vaccine. He added, “Getting tested for COVID-19 was a more dramatic incident than getting the vaccination. We were in Coimbatore at a later date. My father left me at a relative’s place and got tested. He contracted COVID-19, but I did not. Being prodded in the nose with the long buds was more painful than the vaccine jab.”

Strikes, Bandhs, Hartals, and Shutdowns

Strikes, bandhs, hartals, and shutdowns were quite common in Kerala until recently and affected the number of working days in government-run schools for a long period. This was banned by a High Court verdict in 1996. Private and aided schools were not always affected by these strikes.

G. Kumaran Nair, 79, a retired official at Carborundum Universal Ltd., studied in the government school in Kuravankonam, Thiruvananthapuram, during his primary and upper primary years. They had a lot of holidays due to strikes when he was there. He studied at the Salvation Army during his high school years. There were no holidays like in the government school at this mission school.

Dr. K.K. Muhammed Yusuf, 73, a retired University professor, mentioned, “Student protestors used to enter the school and ask us to vacate the premises.” He studied at SRV school, Ernakulam, a government school.

Working days were frequently disrupted until the 2020s in government, private, and aided colleges with strong student political parties. As Vineeth K., 39, jokingly said, it was always “Strikes, strikes, and more strikes.”

Anoop, 43, remembered that in the early 1990s, educational institutions were given several days off when some violent political event happened in a school in the Kannur district. He quoted a radio announcement frequently heard during his school years, “Because of so and so reason, the holiday has been declared tomorrow for all educational institutions, including professional colleges.”

Rain Holidays

If heavy, unexpected rain caused havoc in a large area, schools declared a holiday. Rosily Paul, 82, said that during the late 1940s and 50s monsoon season, “The road in front of our house would be flooded, and we had to wade through ankle-deep water to get to school. But holidays were never declared.”

Thresiamma, 72, who did her schooling a decade later in the same village, added, “If there was a sudden downpour that lasted for half a day and created water-logging in several regions, the government or concerned authority declared a holiday.”

Anoop, 43, mentioned, “There was a cloud burst event when it rained continuously for 3–4 hours in the 1990s. That year, a holiday lasting several days was declared.”

New Holidays

The educational diary for Cochin does not mention any holidays for Pooja, Vishu, Deepavali, or Islamic festivals.

Kripa, 39, mentioned that Pooja holidays used to be for two or three days during her childhood. Sometimes, the school would announce holidays a day late. She added, “Once, many students were absent. The rest of us were taken to the auditorium. They played a couple of movies for us. I remember watching The Sound of Music. That was entertaining.”

Rajarajeshwari Ashok, a researcher, recollected that the students chose the books to be kept for pooja, and not all books were kept at the temple. Rather, only “the books of those subjects perceived as difficult were taken for pooja.”

Holidays Not Celebrated at Present

Certain days were holidays in the past but are not considered important enough now. For instance, on the Sankramam (Sankranthi – the day the sun moved from one Malayalam month to another) days in the Malayalam months, Karkitagom (around July) and Thulam (around October), government schools were given holidays in 1895.

According to Ajitha Radhakrishnan, 43, Ponnekara, these days were important in the past, “Kerala used to see heavy rains in both these months. Various communities prayed on the first day of the month to please the gods so that nothing bad would occur.” The entire house is cleaned, and it is believed that the Chetta Bhagavathi (deity of dirty and decadent things) is banished, and Shree Bhagavathy is invited in.

Family Trips Outside Vacation Period

These are holidays taken during the academic year by a family. Arun Kumar mentioned that before the 1980-90s, people travelled mostly to their ancestral homes and during academic holidays. Since the 1990s, improving the financial situation of the middle and upper classes has made taking a holiday outside Kerala or abroad a fairly common occurrence. There is more flexibility regarding travel during school days/working days. Such holidays depend on various non-academic factors such as a parent’s or relative’s work location, convenience, and impromptu decisions.

Arun Kumar, 60, stated, “Now people take holidays in the middle of the year. There is no waiting for the vacation. People have disposable incomes, so taking such a holiday is not difficult.” He added, “Going on a holiday or balancing it is difficult because everyone has their own opinion and likes and dislikes. Earlier, we would just go and enjoy whatever was there. Now, it is hard to plan a trip because somebody would say they do not want to go there and so on… Now, people have more choices.”

Afsal K.M., 45, music director, recalled one such holiday his family took to Agra and Delhi. Afsal’s father, a university professor, took the family along when he had to accompany a group of students on their study tour.

Weekly Off for Educational Institutions

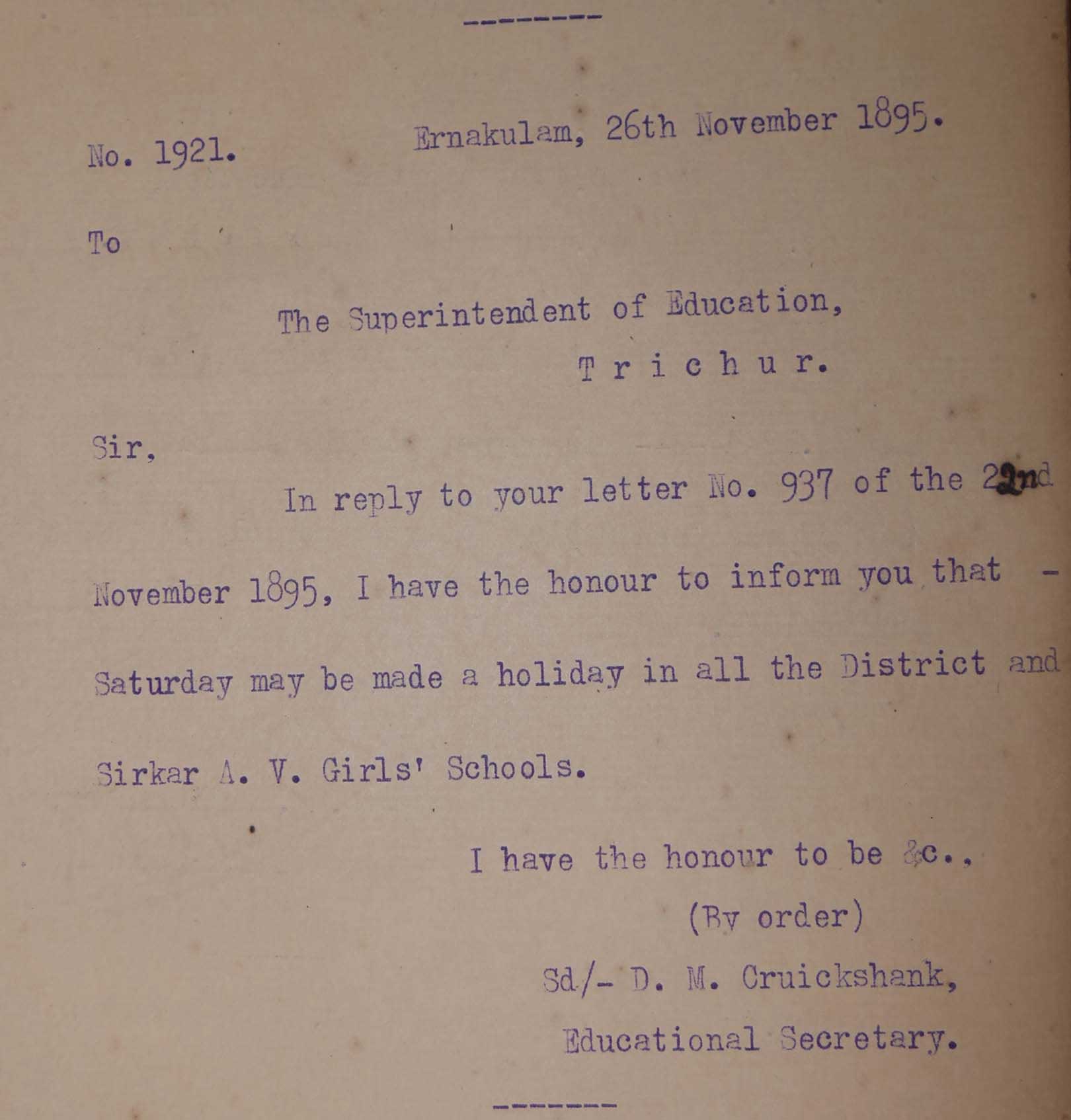

Most educational institutions in Kerala are off on Sundays and Saturdays. Kerala is one of the few states where educational institutions do not function on Saturdays (except for high schools and professional colleges).

G. Kumaran Nair, 79, a native of Thiruvananthapuram, remembered that schools used to function on Saturdays in his childhood. His wife, P.K. Rajeswari Devi, 75, a retired KSRTC employee who studied in schools in and around Eloor, Kochi, mentioned that they did not have schools on Saturdays. “Whenever extraordinary holidays happened due to a strike or for some other reason, Saturday was a working day.”

In Colonial Cochin, the declaration of Saturday as a school holiday started in the late nineteenth century in girls’ schools.

As mentioned earlier, the selection and observance of holidays are influenced by a complex interplay of cultural, social, and economic factors. Understanding these influences can enhance our understanding of the holiday landscape and its significance within Malayali society.