Teak: Boon or Bane

Walking with Lakshmi, Sunil, Aneesh, and Madhavan through Nilambur forests, April 2023

Conolly’s Plot: The First Teak Plantation in the World

On the outskirts of Nilambur town sits the plantation that hosts a 165-year-old teak tree. Popularly known as Connolly’s plot, the world’s first teak plantation was planted in Nilambur in 1846 by the then-district Collector of Malabar, H.V. Connolly. With one million trees, it was spread over 607 hectares (ha) and designed to provide an estimated 2000 trees annually.

After many unsuccessful attempts to germinate teak seeds, in 1843, H.V. Conolly finally located Chathu Menon. Their unique approach involved boiling teak seeds and growing the saplings in water before sowing them broadly under leaves in a nursery. This was the beginning of India’s first viable teak plantations in Malabar.

The British established timber depots in various ports, such as Thalassery and Kollam, to facilitate the export of teak wood to Britain. Since the introduction of the first teak plantation by the British in Kerala in 1842, almost all states of India have introduced teak plantations in forests under different schemes to create or convert existing forests into high-value timber-based forests.

Today, Connolly’s plot is a permanent teak preservation plot in memory of Connolly and has shrunk to 2.3 ha, with just 117 trees.

Teak, ‘King of Timbers’, grows in tropical forests along the Western Ghats, specifically in Travancore, Cochin, and Malabar in southwest India. The trees of the Nilambur forests in the Western Ghats attain remarkable size due to the tropical climate and fertile soil. Growing up to 50 metres in height with a diameter of up to 2.5 metres, these trees yield teak logs of significant size that are highly valued in the market. Moreover, Nilambur teak stands out for its superior colour. The oily heartwood of the teak tree has a rich, golden-brown hue that darkens with age, which is highly sought after in the market.

Following the defeat of Tipu Sultan in the Third Anglo-Mysore War in 1792, the British took control of South India. The Western Ghats, abundant in valuable timber and species such as Teak, Anjili, and Rosewood, were particularly interesting to the British colonial state. By the early 19th century, the collection of natural resources, particularly teak from the Western Ghats, was at its highest, with indiscriminate felling and overexploitation of teak forests. The colonial state began conserving and preserving teak species that were well-suited for humid tropical climates and salt water. Malabar teak was used to make articles that could be exported and for shipbuilding in port towns.

Other Plants in a Teak Plantation

“The growth of tuber crops has been severely hindered as a consequence of teak expansion, jeopardizing their viability.” … Sunil & Madhavan.

A teak plantation, with numerous giant trees closely planted, with enough space between them for light to reach the ground, dominates a large stretch of the forest floor. Teak roots spread horizontally in the topsoil layer, and the tree consumes most of the soil nutrients and moisture to ensure its survival, so it does not allow other plant species to grow around and under it.

Other trees, creepers, and shrubs disappear gradually in a teak plantation, making it useless for local people and wildlife. Furthermore, the slow decomposition of teak leaves makes the situation unhealthy, as they accumulate on the ground for prolonged periods, generating elevated temperatures within the soil.

“After the forest became a plantation, the proliferation of medicinal plants, which were once abundant in this area, has been dramatically impeded.” … Sunil, Village Nedungayam, Nilambur.

History and Memory: The People of the Forest

“We, the Adivasi people, used to govern the forest. They took advantage of our knowledge of the forest and took over and started ruling the forest. We were turned into slaves by the British.” … Madhavan

Different oorus co-exist inside the forest—Cholanaikkar, Kattunayakar, and Paniya communities. These oorus have different stories based on their levels of interaction with the outside world. The Cholanaikkar community resides in the deepest parts of the forest, while the Kattunayakar community occupies an area which is not as deep. The Paniya community is located in the forest, close to the town.

Among them, the ‘Chola’ (evergreen forest) and ‘Naikkan’ (king) people of Nilambur forests are among the few surviving hunter-gatherer communities in the country, and some still live in traditional rock cave shelters. Today, their language is a mix of Kannada, Tamil, and Malayalam.

Colonial Arrivals and Locals

The Kattunayaka and Paniya gothrams inhabited the area before the British arrived. The Paniya community worked on the land, while the Kattunayakar and Cholanaikkar communities hunted animals and scavenged honey and forest produce. The Muthuvan community had the best relationship with the Kovilakam.

All these lands used to belong to the Kovilakam. The Kovilakam lands were used by Britishers, causing a rift in the relationships among the communities. Adivasi communities within the forests maintained their connection, while others outside the boundaries were restricted. Forest laws restricted free movement, deteriorated relationships, and prevented reuniting.

History and Memory: Breaking a Connection

“All kinds of trees and plants existed inside the forest. This was not a plantation at the beginning. It was a normal forest—all kinds of trees were there, small and large.” … Madhavan.

To work in the Nedumkayam forest plantation, the British recruited individuals from various resident Adivasi communities. The primary task assigned to the workers was to catch and train elephants, while another crucial task was to plant teak saplings. These significantly changed their existing lifestyles and dietary habits. Outside the plantation, trees were cut down indiscriminately, and the forest department cleared natural forest areas under the guise of agricultural benefits for the community.

Initially, the forest department cleared a designated area, and teak saplings were planted. Local community members were informed they could engage in agricultural activities in this plot for three years. However, at the end of this period, they were required to relocate to another plot for another three-year cycle. This practice was implemented due to the significant growth of the teak trees by the fourth year. Sunil, a resident, said that local community members expressed their discontent, feeling that although the land belonged to everyone, the forest department exploited it for itself.

The Adivasi communities, like Paniya, who lived outside the forest boundary, could not walk into the forest like before. This led to a break in relationships between families and communities who lived inside and outside the forest. They could not see each other because of the restrictions caused by the Forest laws. This led to a younger generation not knowing each other, even though their elders shared a good relationship.

Nilambur Forest Timeline

“Trees, creepers, and shrubs in this area have disappeared gradually, and it has become useless for local people and wildlife.” ... Sunil & Madhavan.

Forest as Work: Controlling Livelihoods

Until the late 1960s, the community led a secluded life with minimal contact with mainstream urban society. Vinod, the first of his community to pursue a PhD, says, “The food style has changed; unlike in the past, we need money to buy food materials. We only get limited materials and must buy them from outside due to our big family. Traditionally, we have the right to collect materials from a particular area in the forest. My family, Panappuzha, can collect from the Panappuzha area only. We cannot collect from areas under other families. Which is why we preserve our area.”

The primary occupation was mainly honey collection, which extended to fishing, preparing and trading resins, including prized commodities like frankincense, and gathering medicinal plants, vegetables, fruits, and mushrooms. Commodities such as mangoes and gooseberries were procured and commercially traded. Concurrently, the construction domain using traditional materials, exemplified by bamboo, emerged as a prevalent occupation.

Life in the Forest Today

Regrettably, the passage of time has witnessed a shift towards preference for brick and cement in contemporary house construction, ultimately leading to a waning of proficiency in traditional construction methods. “It is not that people have forgotten skills like, using bamboo in house construction. Most have forgotten how to generate income from the forest itself,” said Sunil. A palpable consequence of this evolving trend has been the gradual neglect of knowledge and skills related to forest-based income generation, thus ushering in a concerning era of waning familiarity with such invaluable practices.

Over the last two decades, there has been a discernible decline in the availability of forest produce, prompting a significant shift in occupational patterns among the populace. The people of Nedungayam, Mundakkadavu, and Pulimunda ooru have predominantly gravitated towards engagements in loading and unloading operations. Notably, many of these individuals are affiliated with labour unions and rely heavily on the proceeds generated from teak plantation activities. Their daily responsibilities entail loading trees, clearing shrubs, and managing fire line duties within the forest’s confines.

Life in the Forest Today: Inter-relations

“We do not celebrate Onam and Vishu. All those are recent and new festivals. Each gothram (community) will have a varshika akhosham (yearly festival). Most celebrations are related to the collection of produce from the forest. We leave to collect the produce only after prayers. Everyone knows that there is a god. We don’t know what or who that god is. We imagine this God to be nature,” says Aneesh.

“Paniyar, Muthuvan, and Kaattunayakar all have their way of praying. All these poojas happen in March, April, and May. If it’s a Paniya festival, the mooppan (head) of Nayakkanmar will be invited. Similarly, Nayakkanmar will invite the Paniya mooppan too. Such mutual invitations are a way of showing respect. That’s the way it has always been, and that is how it remains now. Vilaveduppu ulsavangal (harvest festivals)—is held when we collect honey or other tuber, an example of one occasion when the prayer is held.”

Lakshmi also spoke about the importance of praying before collecting honey. “When we collect honey, we keep a vettila and adakka (beetle leaf and areca nut) and pray. It is called malakku kodukkuka, which we offer to the gods before consuming. If we don’t give to the gods first, some accident might occur. Honey is collected at night so it can be dangerous.”

The locals compared themselves to individuals of African origin who are disconnected from their relatives in their homeland due to the forced displacement of their ancestors. People living inside the forest were given pattayam by the Forest Act of the 1970s—between 2, 3, or, at most, 5 cents, which is inadequate for housing.

“We depend on work like koolippani (daily wage labour) outside the forest and don’t get enough from the forest for our livelihood. So, we have to go out. Young people do not know the ways of the forest.”

Missing the Forest for the Trees: GI Status with Mixed Feelings

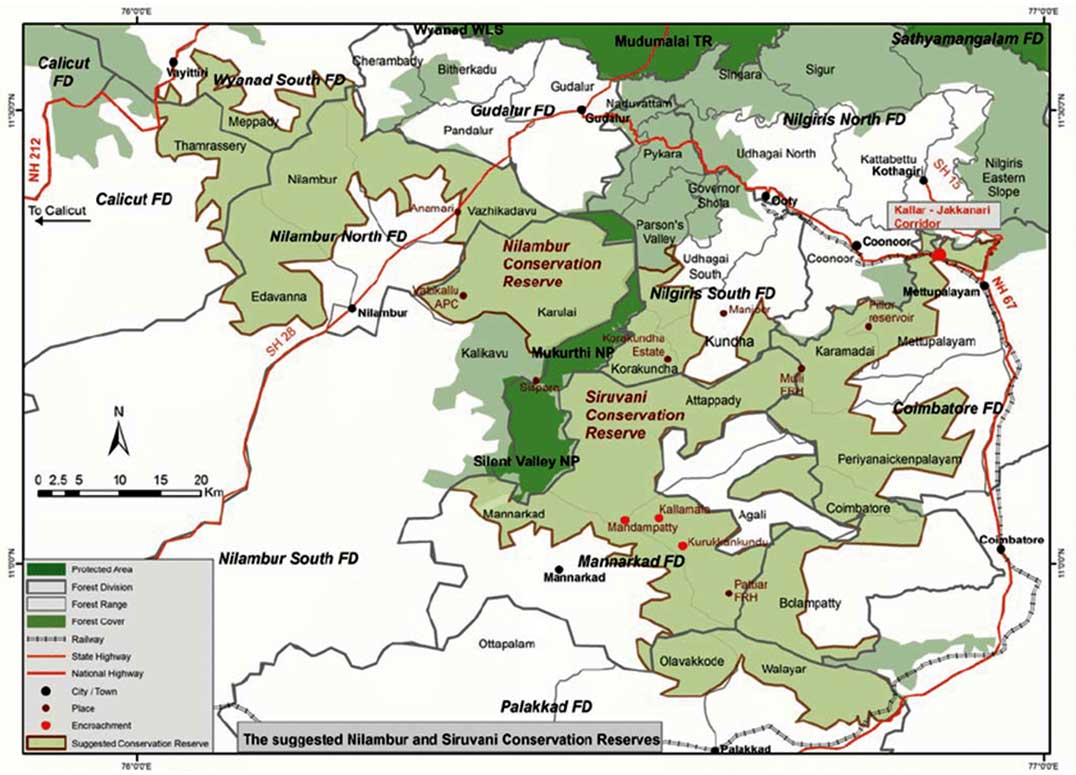

In 2023, joint efforts by Research institutes, Universities, Kerala Forest Research Institute Department of Forests, and various NGOs led to granting GI (Geographical Indication) status to Nilambur teak. The first instance of forest produce being added to the roster of products with the GI tag from India draws attention to the social and political effect teak has had on the forests of Nilambur.

Will the global attention with the GI tagging of Teak let the Nilambur forests remain so, or will it convert the forest into a plantation, like Rubber elsewhere in Kerala?

Moreover, can it draw attention to people’s histories and local ecologies in this corner of the world, describing how trees and peoples thrive because their lives and futures are interconnected and coexist?

Whose forest is it anyway?

Not the forest dweller, with less work and precarious lives

Nor the animals poached, killed, and forgotten

Or will it be the government’s, as a plantation owner, not a forest carer.