Therapeutics to Cosmetics

Health, Hygiene, and Medicine

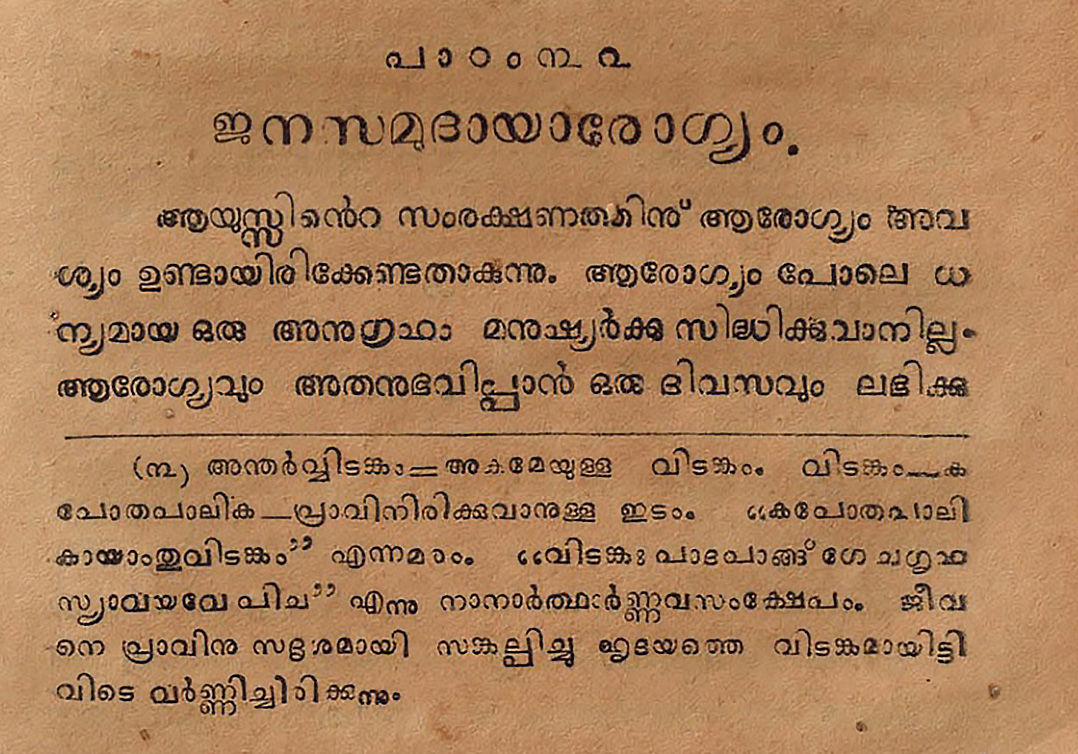

Ayurveda has been practised in India for thousands of years. However, its commercialisation has been a complex process involving social and cultural factors as much as medicinal. This started in the early 20th century when modern medicine was set to take over the area of health, hygiene, and medical treatments. In the 19th century, schools and textbooks were the sites through which the government intervened by introducing ideas like shuchithwam (cleanliness) and arogyam (health). The concept of hygiene was already present in missionary activities, literature (including magazines and novels), and the public sphere in connection with the fear of contagious diseases.

“Kerala Sanchari advised that sanitary science should be made a compulsory subject at the primary level.”

– Sreejith K., 2013

Changing Ideas of Cleanliness

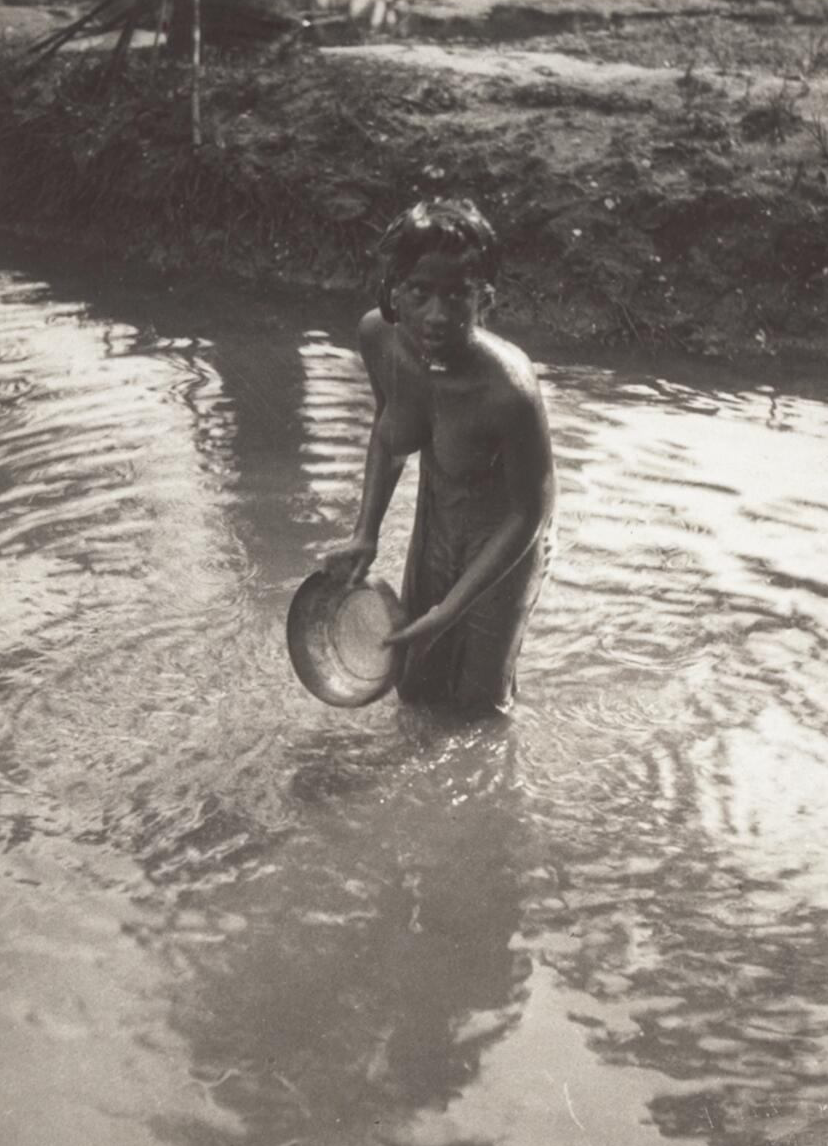

Capitalism, technology, colonialism, caste and political movements, education, and land-use patterns were changing Kerala. Consequently, the region was in a state of transition from a caste-ridden society to a more complex, yet hierarchical one. The idea of an egalitarian society that stood against untouchability and colonialism emerged in the early 20th century. At the same time practices related to the perception and well-being of the body were being transformed.

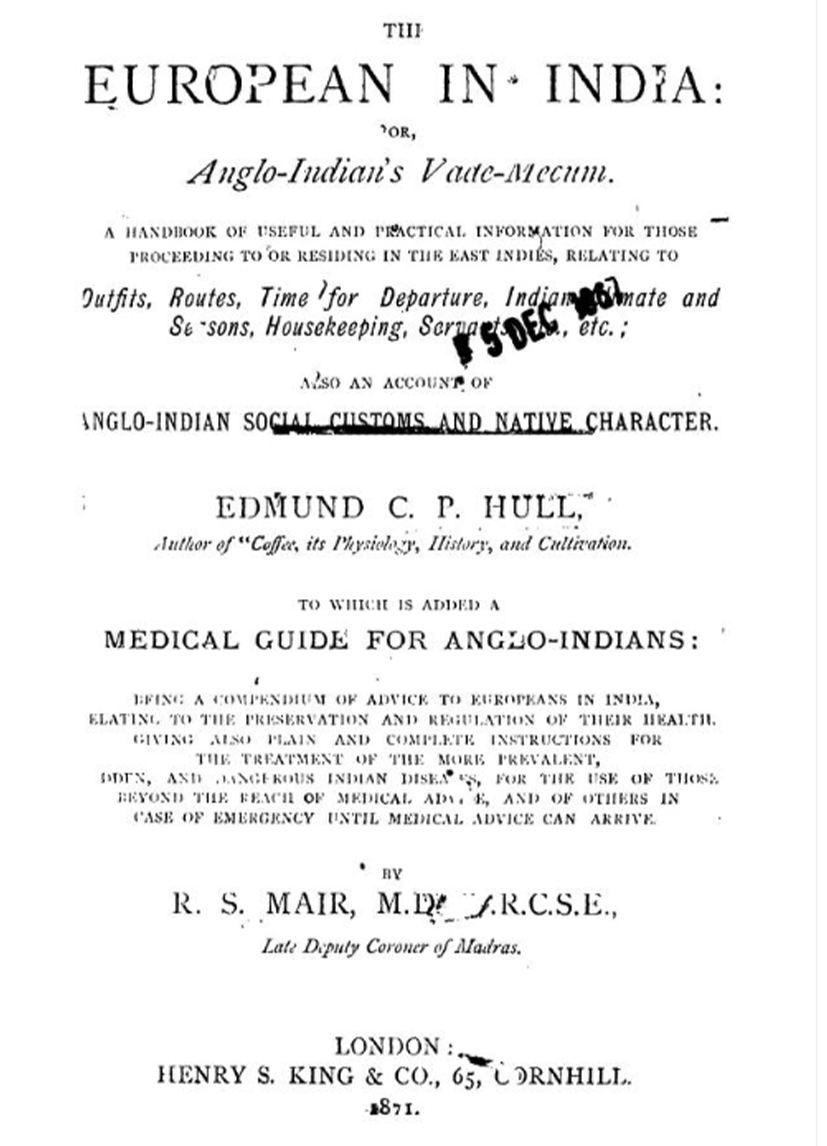

The existing idea of vrithi (cleanliness) was not equivalent to the new colonial notion of health and hygiene. Practices like applying various types of oil on the body, chewing and spitting out betel leaves/paan, and so on were scrutinised and termed as bad habits. For e.g., the smell of oil (used in oil baths) was described as “fetid, disgusting, and nauseating,” (The European in India).

From Purity to Hygiene

“We argued that a bath was to maintain hygiene (suchitwam), not to remove caste pollution (ayitham). Ayitham means asuchitwam; where there is suchitwam, there is no ayitham, we argued to the older generation.” (p. 31)

– B. Kalyaniamma, editor, writer, and teacher, in her autobiography Ormayil Ninnu, 1964

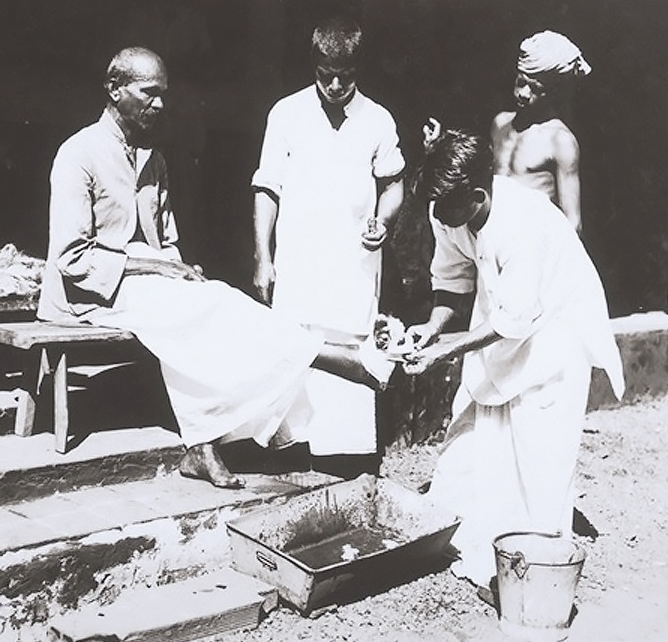

The shudham debate was gradually transformed into a shuchithwam discourse, i.e., the health of the people based on hygiene and cleanliness. A corporeal practice was transformed into a secular and medical idea. This was accelerated by the intervention of medical science. The old ideas were absorbed into the new discourse.

“The ideas related to caste pollution emerged periodically, especially since certain castes were seen as inherently ‘unclean’.”

– K.P. Girija, 2023

The ideas on shudham/ashudham were connected to people’s position in the caste hierarchy. Lower castes were blamed for not being aware of how to be clean and healthy. The old way of talking about untouchability and the physical habits of different groups that had to do with purity and pollution turned into a medical, social, and secular discourse.

Social reformer Sree Narayana Guru was learned in Ayurveda. Though he did not practise, when people asked him for help, he used to provide them with either advice or medicines. He asked people to maintain cleanliness with whatever resources they had.

The Process of Soap-Making

Plant-based oils have a long tradition in Indian soap making, with ingredients like coconut and neem oil being used for centuries. Soap is created by mixing fats and oils with an alkali, either wood ash, lye, or sodium hydroxide in a reaction called saponification. Translucent glycerine soaps are made by adding alcohol and sugar.

In the late 19th century, Prafulla Chandra Roy from Bengal, author of the History of Hindu Chemistry (1902/1909), began producing glycerine soap. He used Western technology and indigenous ingredients at the Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Works in 1899.

In the mid-20th century, synthetic detergents gained popularity worldwide due to their lower cost, higher lathering ability, and effectiveness in hard water.

Commodifying Hygiene

Soap production did not happen in a void. Before this period, toilet soap was a commodity or a luxury that was only used by affluent families. Laundry soap was available, affordable, and was used for both washing and bathing. Local Ayurvedic practitioners, Godrej, Unilever, Tata, and Peirce Leslie were some of the groups making soap at that point.

Many soap factories were set up during the World War I years to utilise the excess stock, like coconuts, sandalwood, and so on. In 1914, the Madras government set up the Kerala Soap Institute and, in 1916, the Madras and Mysore governments set up soap factories in the respective states.

By the 1920s, indigenous soap manufacturers had captured half the soap market. 501, the century-old laundry soap, was already in production by then. The Tata’s decided to name their laundry soap 501, after a French brand called 500. They did not want a British name since Levers, a British company, was their main competitor in India.

Chandrika Soap

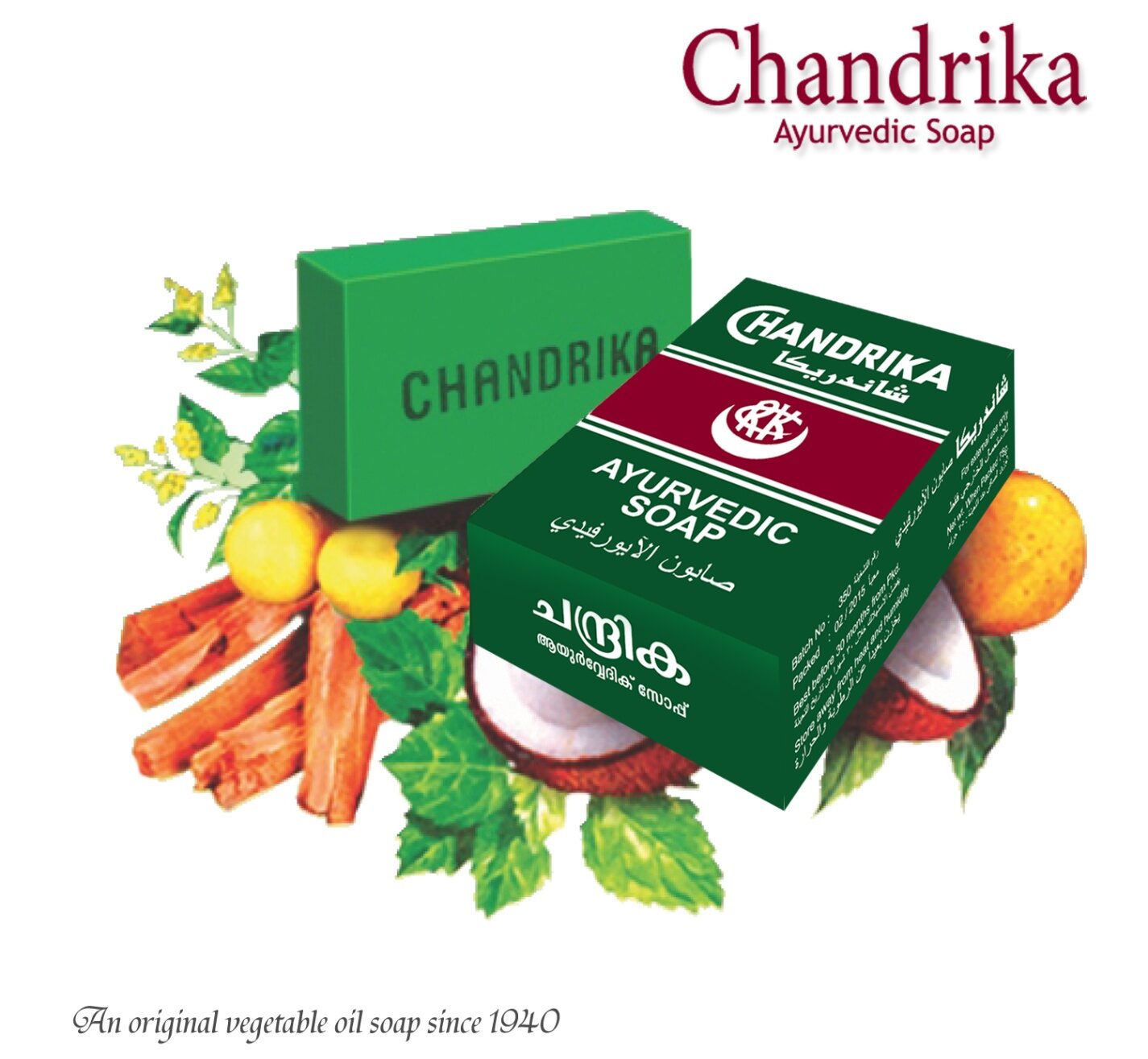

C.R. Kesava Vaidyan (1904-1999) intervened in the field during this period of transition. He started manufacturing Chandrika in the 1940s. A teacher and follower of Narayana Guru, he was the treasurer of Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Sangham (SNDP) for years. He was also a disciple of Ramananda Swamikal, a learnt Siddhavaidya.

Ramananda Swamikal, Kesavan’s guru, had the formulation for a medical paste that could be used for skin diseases. Swamikal used Marottica oil, known for its therapeutic properties, especially in the treatment of leprosy, to make soap. He allowed Kesavan Vaidyan to use the same oil to prepare a new soap.

Ramananda Swamikal’s soap was called Saseendra soap. Saseendra means the ‘moon’ while Chandrika means the ‘light of the full moon.’ Both Saseendra and Chandrika were advertised as being good for scabs, freckles, sycosis, and acne. “Though both the soaps were in the market concurrently, in practice they did not compete with each other,” said K.P. Girija.

C.R. Kesavan Vaidyar’s mother was a Vishavaidya practitioner, but he did not learn from her. Once he learnt Siddhavaidyam from Ramananda Swamikal, he started producing a range of products including medicine for children under the name Chandrika. After a period, he stopped the other products and focused on the soap.

Building Patronage

Kesavan advertised his soap in innovative ways. He got dignitaries and public figures to write letters of recommendation or appreciation and published them in magazines, especially Vivekodayam, the mouthpiece of SNDP. He was the publisher and funder for the magazine. Film actors like Prem Naseer wrote acknowledgement letters for Kesavan while prominent poets, like Vallathol Narayana Menon, wrote poems about the soap; social reformers, advocates, and doctors gave certificates saying the soap was good for skin diseases.

Kesavan advertised in Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, and English newspapers. He sent the soaps for review to newspapers like Gomathi, Kaumudi, and so on at a time when only books were sent for the same. Kesavan printed calendars with the advertisement of Chandrika.

He advertised in theatres that were evolving in various parts of Kerala. In a boat race, he used a huge banner of Chandrika in one of the boats; at the Thrissur Pooram, one of the elephants carried the advertisement of the soap. It was not just through banners and print, Kesavan used to carry the soap in a metal box to exhibitions either by walking or by bus.

Emphasising Vegetable-ness

Chandrika was secretly known as the ‘Ezhava soap’ and certain upper-caste families refused to use it because it was made by an Ezhava practitioner. Kesavan overcame caste taboos, transforming the Ezhava soap into something acceptable to everyone. He marketed Chandrika as the only original vegetable soap produced since the 1940s. Hence, people who did not use soap made of animal fat were interested in buying Chandrika.

Initially, the soap was sold through pharmacies with a prescription from either Ayurvedic or Allopathic doctors. Later, it became a free-floating toilet soap.

The company now produces a range of soaps and shampoos, advertised through multiple platforms including social media. Kesavan Vaidyan’s company that owns Chandrika has the right to sell Chandrika in countries other than SAARC countries. Godrej has the rights to produce four types of soap named Chandrika using the same ingredients, which are sold across South Asian countries, excluding India.

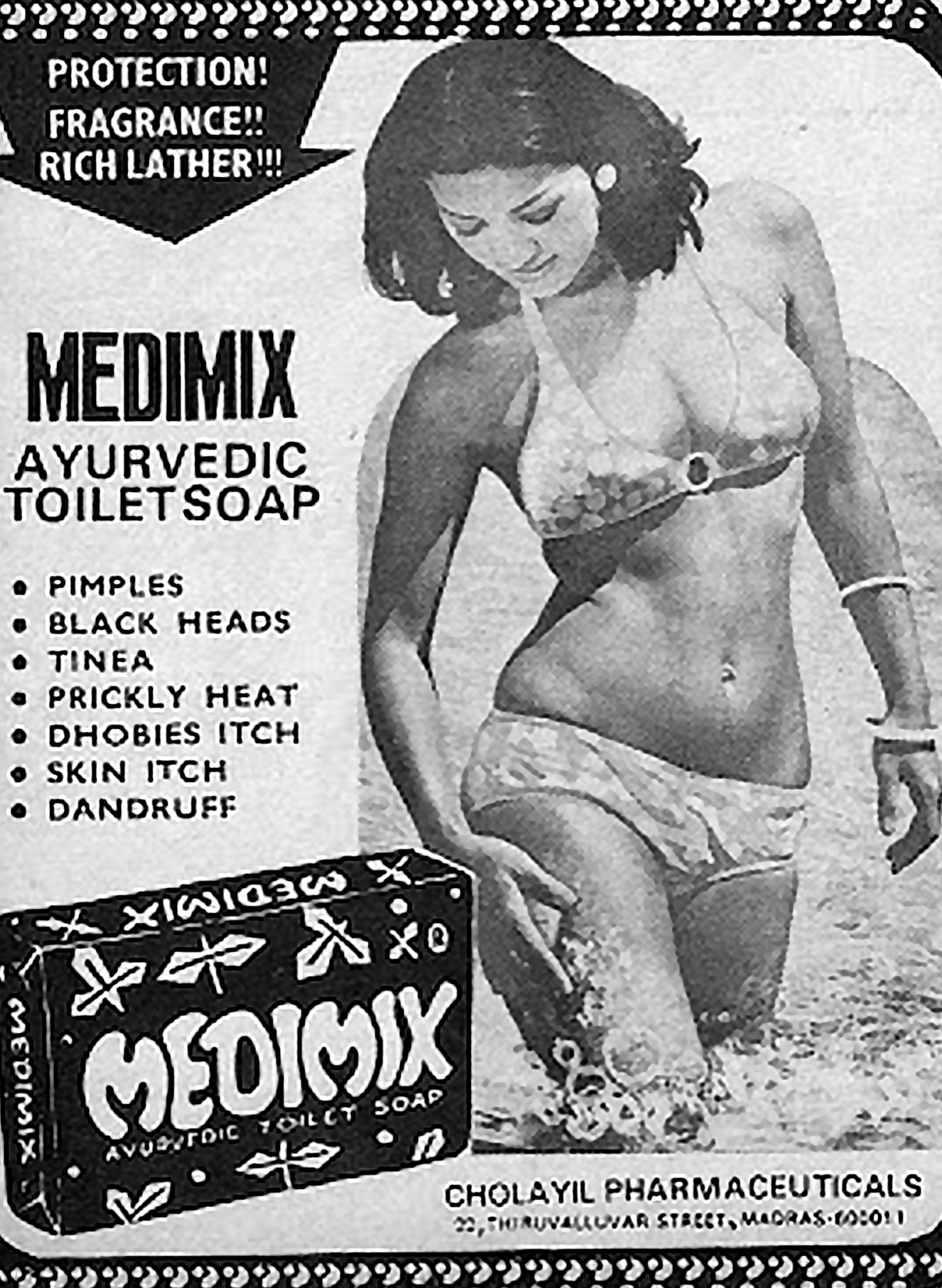

The Medimix Story

An Allopathic doctor, V.P. Sidhan (1931-2011), from the Ezhava community worked in Chennai as a Railway doctor in the 1960s. Among his patients were sanitary workers, with inadequate safety and protection, who frequently contracted various diseases. Sidhan treated them successfully with a secret family formulation using Viprathi oil, and a mixture of medicines. However, the traditional application methods were cumbersome, and he was requested to make something easier. By the 1960s, Sidhan and his wife started making a soap with the oil at home, and began its distribution to the workers and others.

At first, Medimix soap was only available on prescription from either Ayurvedic or Allopathic practitioners. Sidhan used to sell the soaps through Parvathy Pharmaceuticals, in Chennai. During the launch of Medimix, the company publicised the use of a secret family formula, the Viprathi oil, in the manufacturing process. Viprathi oil is made from eighteen Ayurvedic herbs.

Over the years, it shed the image of medicated soap and started advertising its products as having Ayurvedic properties but meant for everyone. Currently, the company produces a range of products for skin care.

Transforming Ayurveda

Secret family formulas were part of various Ayurvedic traditions. Ottamuli is one such, which can be a formula made of various Ayurvedic ingredients and used to treat a specific disease or a single formula used to treat various diseases like jaundice and piles. These formulas are not generally shared with other practitioners or practitioners following other Ayurvedic practices.

Merging Traditions

“A good grade of soap containing a small quantity of prussian blue and probably a little phenol.”

– Good Housekeeping, 1914

Cuticura is a brand that has been in existence since 1865 and developed in the USA. Cuticura presented itself as a “Skin-care expert since 1865” and its formulation has remained relatively unchanged since then. Cuticura was bought by the parent company of Medimix, the Cholayil group, in 2021 who did not change the brand name.

Mildly Medicated

The deodorants, powders, and bathing soaps produced under the Cuticura brand are not marketed as Ayurvedic products, rather they have “ingredients from mother nature” and are “equipped with healing properties.” The brand changes from a chemical product to a mother nature product.

Back to Nature

Consumers, aware of the harmful effects of chemicals in cosmetics, look towards products that claim to be based on ‘years old’ Ayurveda. But, these claims do not reveal anything about the authenticity or the expertise of the companies and firms that make these products.

Traditional healthcare products are produced and marketed by both small and large-scale entrepreneurs. These products include both therapeutic and cosmetic items that cater to various health needs. However, they had to package and market their products in a way that the caste position of their founders was glossed over.

Chandrika and Medimix are examples of two products that set the stage for therapeutic products to transform into cosmetic products in the twentieth century. Today in Kerala, people buy products not only for their caste legacy of Ayurvedic or Siddha practice, but also due to the belief that they are buying unadulterated, pure products.

Return to Tradition

Companies producing Ayurvedic, Siddha, and Unani products, like Kama Ayurveda, Biotic, Kottakkal Aryavaidyasala, and Thaikkattu Mooss, advertise their products not as cosmetics but as Ayurvedic combinations. Kama Ayurveda states its authenticity through ancient Vedic texts and Kerala’s Ayurvedic connection.

With the advent of the digital era, these entrepreneurs have found new ways to reach their customers through online platforms. This is especially beneficial for small-scale producers who do not have the resources to invest in professional advertising. The digital platform allows them to showcase their products and connect with potential buyers more easily. Their websites are optimised for the product. They have relevant content that educates, entertains, inspires, and persuades customers to buy the products.