Topasses of Cochin

The Portuguese Governor in India, Afonso de Albuquerque’s policy of Politica dos Casamentos, had strived to create a loyal local population through intermarriage. The firangi (foreigners) men were encouraged to enter into marital relationships with local women, and the children of such marriages were called Mesticos (Mestizo). Gradually, a new subsection grew when the Mesticos married local women.

Mixed Ancestry

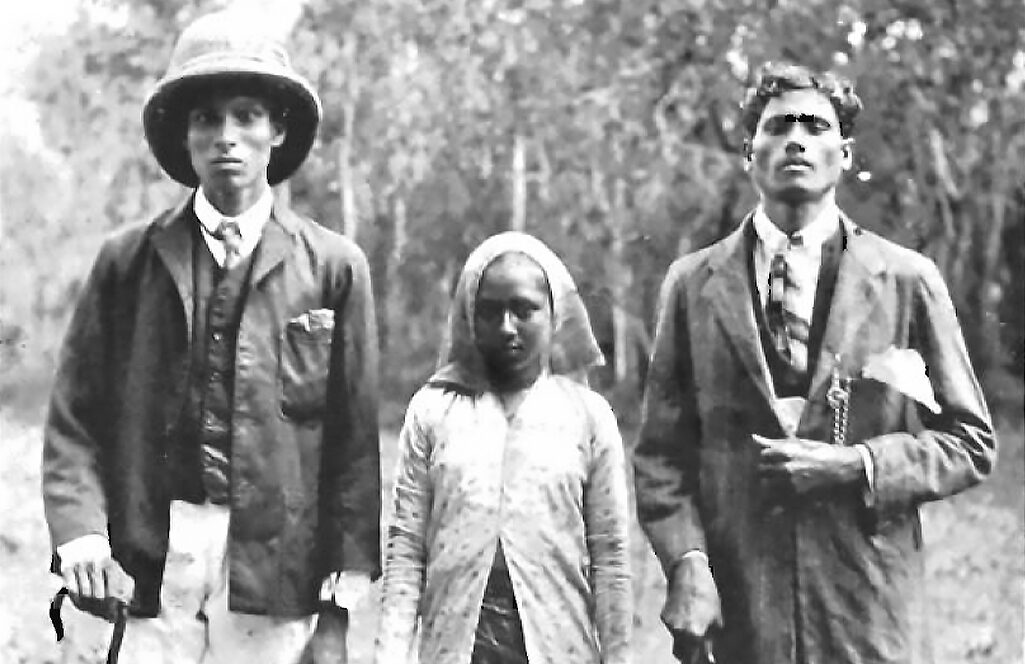

The name ‘Topass’ provides a handful of explanations. For one, the Portuguese called them gente dos chapeos or the ‘hat people’ because of their habit of wearing hats in public. The word tupasi is a derivative of the Marathi word duibhashi, meaning a person who speaks two languages (as a translator). Finally, topa-chi, meaning musketeer, also counts as a possible origin of the word. All versions unveil a distinct face of the community’s identity—a testament to the community’s vibrant past.

Dutch accounts of 1663 describe the Topasses uniformly as “haughty, lazy, and conceited” and as “idle as well as proud, and will seldom work as long as they have any money.”

Razing of Cochin

The Dutch invasion of Cochin was a gruesome affair. The Portuguese fort of Cochin was destroyed and reduced to half its size. In 1663, 400 Topasses fought alongside the Portuguese in Cochin against the Dutch. Fearing persecution, the Topass population inside the fort moved to neighbouring islands, where they continued to live.

At the time of the Dutch arrival, the Topasses formed half the population inside the fort. They were employed in various jobs, including shipbuilding, smithery, carpentry, agriculture, and fishing. Some were used as translators and soldiers. Gardens and fields were rented out to them. They also reserved the privilege of selling refreshments to the company’s ships.

“On the square in front of each church, the Dutch lit a big fire and burned the ornaments therein—statues, crucifixes, holy pictures, missals, and everything pertaining to the sacred worship. The next day, the keys to the city were delivered. Rickloff, the Dutch general, gathered the population under guard and let soldiers plunder the city for three days.”

– Archbishop Joseph Sebastiani, 1663

Home Town

According to the treaty between the Dutch and the Raja of Cochin, protecting all Roman Catholics was a Dutch responsibility, and the Topasses became the subjects of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). This meant that the Raja of Cochin had no jurisdiction over them if found guilty of any crimes. This arrangement soon became a nuisance, as soldiers and troublesome individuals ventured into the Raja’s territory and committed various crimes, from drunk and disorderly behaviour to killing cows, only to escape back into the Dutch territory to avoid persecution.

Despite their Portuguese descent and Catholic faith, the Dutch soon called the Topasses back to the fort—the new rulers required a serving class. At the fort, they worked as translators and soldiers, becoming the backbone of the VOC in Fort Cochin and continuing the Portuguese legacy into a new era under a new regime.

The Topass spoke a creolised form of Portuguese influenced by Malayalam and the other tongues of cosmopolitan Cochin. Called ‘Cochin Portuguese’, the language survived well into the 21st century until its last speaker, William Rozario, died in 2010.

VOC and other Armies

The Topasses were preferred over the natives by the colonial armies for their European ancestry, which made it easy to forgo caste restrictions and use firearms.

In the mid-18th century CE, the Dutch used Topasses to man watch posts along the Arabian Sea to counter the increasing smuggling of pepper. Besides, they were often recruited and sent away to fight the company’s wars in the Dutch East Indies or present-day Indonesia.

Some Topasses were part of the British garrison, which blocked the Dutch admiral Ryckloff Van Goens from landing in Bombay. And when higher-caste Hindus refused, for religious reasons, to serve aboard ships, they served on British frigates against the Malabar pirates.

Topasses from Ceylon were deployed to counter the advances of Travancore. Later, the captains of the Topasses, Ezekiel Rabbi and Silvester Mendes, were sent to Mavelikara to reach an agreement with the rajah of Travancore on behalf of the Dutch.

Thus, with the coloniser’s blessings, Topasses became a formidable mercenary force in the military landscape of Malabar.

Surnames like Otambattil Avara Kappithan (Captain Cochinyil Lodikar), Nanayil Chandy Alparis (Alvares), Mundiriyil Avara Kappithan, Kuttasseriyil Vad’ki Araju reveal their martial heritage.

Dressing as identity

The European hat and trousers acted as a symbol of separation from the rest of the Indian population and of a closer link with the European rulers. However, that did not mean that the life of the Topass community in Cochin was easy. A Diacony or charity fund had to be paid for wearing shoes and stockings.

The Dutch divided the native Christians living along the coast into two groups: the Mundukar, who wore a white cloth and puggry, and the Topasses, who dressed in hats and trousers. A captain or a commander presided over the community. Topasses needed to obtain a letter of consent from the commander to marry.

Like the community’s male members, the womenfolk followed European dressing with their coloured loincloths and knee-length loose coats. Later, they adopted the kebaya from the Malaccan women and sarongs from those from Macau in China, large groups of whom were settled in Cochin. The tradition of wearing red and black chequered kebaya continued well into the early decades of the twenty-first century.

“In the 1970s, I had to travel to Thevara, the only place in Cochin that sold kebaya cloth, for my mother. By this time, it was only the older women who continued to wear it.”

– Romey Correya, Moolamkuzhi, Ernakulam 2024

The Dutch called the Topass marriage customs ‘peculiar’, as the bride probably never saw the groom before the marriage. However, this was common in the region, and unlike what the Dutch expected, the married couple never walked side by side, but the husband walked ahead, and the wife followed.

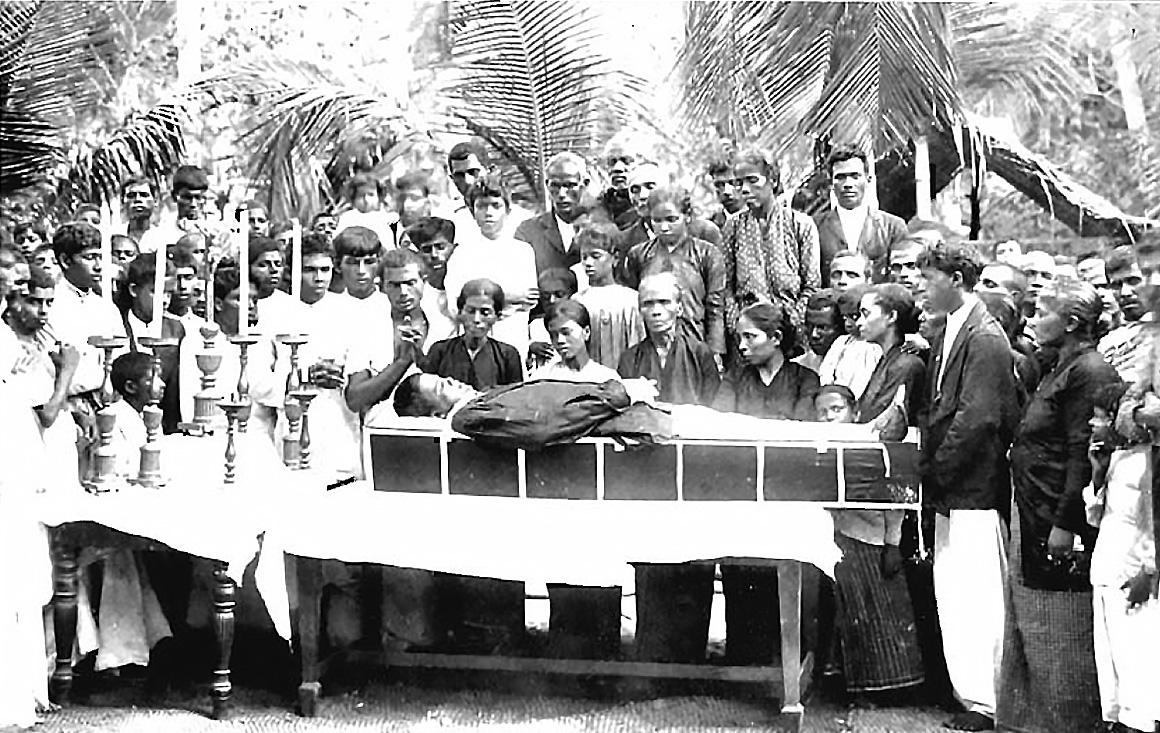

During funerals, Topasses mourned by wearing lining-less, black coats inside out and letting their beards grow. Upon death, the body was covered with a cloth on which a large cross was embroidered and then taken away to be buried on the island of Vypin.

Catholicism in Cochin

On a typical Good Friday, a Topass family participates in a procession held outside the church with a person dressed as Christ carrying the cross. Later the same day, the congregation flagellate themselves with scourges made of rope. These scourges had knotted ends with ‘bits of broken glass and lumps of wax’. To bear the pain, they get intoxicated by drinking arrack.

Besides, St. John’s Eve was a grand celebration. A fireworks ceremony was held in honour of the saint. The following day, i.e., St. John the Baptist’s Day, was marked by children dressed up in garlands and green boughs. At the beginning of every monsoon, the parish priest would visit every house and sprinkle holy water to ward off evil spirits.

While endorsement of superstitions was nothing new in Christian communities in Kerala, Topasses differed from them by a lack of any observable Hindu influence, even to the extent that they did not use thali (marriage necklace pendant).

Today, priests from Cochin Diocese credit the Portuguese with introducing processions and celebrating feasts among the Catholics.

Hindus made up a majority of these Portuguese converts, the bulk of whom were poor, lower-caste people wishing to escape caste discrimination and lift their social status.

The few former higher-caste Hindu converts, the Anjoottikkar (the 500), who were converted fishermen, and the Ezhunoottikkar (the 700), who were the descendants of the soil slaves, continued to maintain the caste system with the Topasses or Munnoottikars (the 300). This community had sprung from old Portuguese settlers and low-caste women. Even today, certain catholic dioceses and parishes in central Kerala are segregated based on caste differences.

In the Twentieth Century

Over time, the term ‘Topasses’ fell into obscurity, but the community continued to be referred to by different names, Munnottikar, Feringi (parangi), Chattakar, Luso-Indians, etc. The community remained relevant over the years, securing employment with their handiwork in boatyards and their grasp of European languages in offices.

Under the British reign, the community enjoyed reservations in government jobs. “Had it not been for the Eurasians (people of mixed European and Asian parentage), the British Empire in India would have collapsed,” writes the Union of Anglo-Indian Associations.

After independence, many worked their way into earning expertise in engineering and administrative work, like the father of Ralph Faria, who served in the British army during the Second World War and was later posted at the MES (Military Engineer Services). Likewise, Cochin Harbour was full of carpenters and mechanics from the community.

The caste division crept into the present church system, with the dioceses of Cochin, Alappuzha, and Verapoly based on the caste divisions between the Anjoottikar (the fishermen) and the Ezhunoottikar (the land labourers).

This ‘ethnically engineered’ community, which acted as ‘shock absorbers’ between the Europeans and the natives, who ushered in modernism through their language, music, and tradition, was almost buried in the annals of history until 1970.

The 1970 Incident

Indian crew on newly bought ships and submarines from the USSR noticed an ‘unfair’ issue after landing in India. While sailing with a crew of mixed nationalities from the USSR and India, all crew members undertook toilet cleaning duties on rotation.

However, on arrival in India, having specialised personnel (Topass) to clean toilets on other ships struck the ‘Topass-less’ new vessels as ‘unfair’. This caused ‘ugly’ protests that were quietened with corrective action, providing some Topasses as crew on each ship after arrival at home-port.

This practice continued, and a 2019 newspaper advertisement has a hiring called ‘Sanitary Hygienists’, earlier called Topass, revealing this shameful practice still exists in the Indian Navy.

Today, designated toilet cleaners converge caste and uniformed hierarchies in this practice. These uniformed sailors clean toilets under peacetime conditions and man the ammunition supply chain and emergency-aid stations in battle conditions. Though the word ”Topass’’ traces its origins to the Portuguese era, the present usage has a negative connotation referring to seamen of the lowest rank.

This post in the Indian Navy, what Admiral Sampath Pillai (retd) calls a “relic of our (India’s) caste system, and the horrible arrangement we call “untouchability” is what caused the ‘morcha’ of 1970.”