“In Tholpavakoothu history, shadow puppetry is believed to be the first art form in the world. It comes from holiness, nature, sunlight, shadow, and the human movement itself”. - Ramachandra Pulavar, 2013

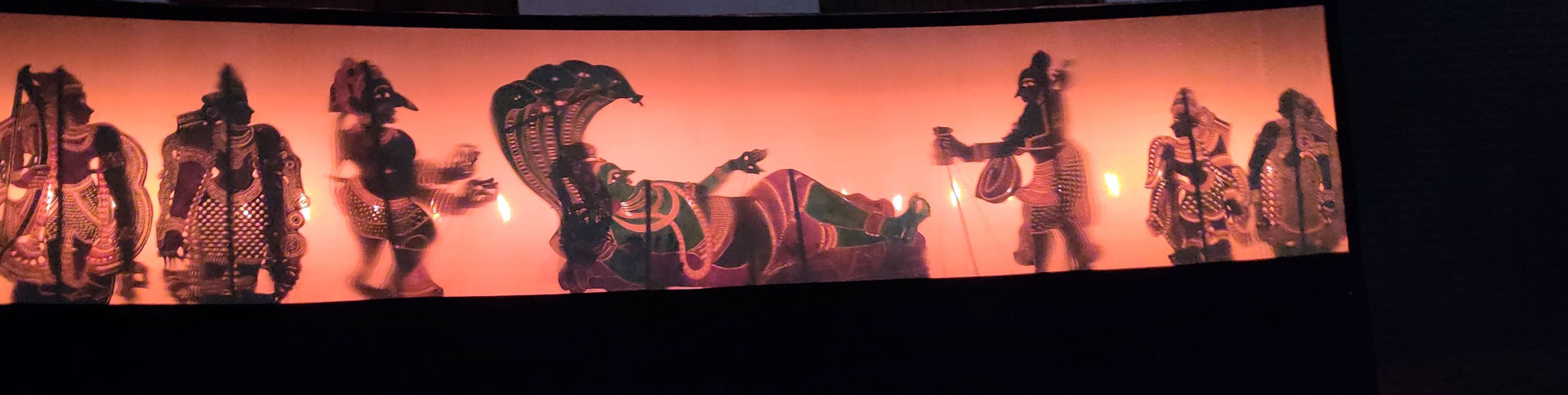

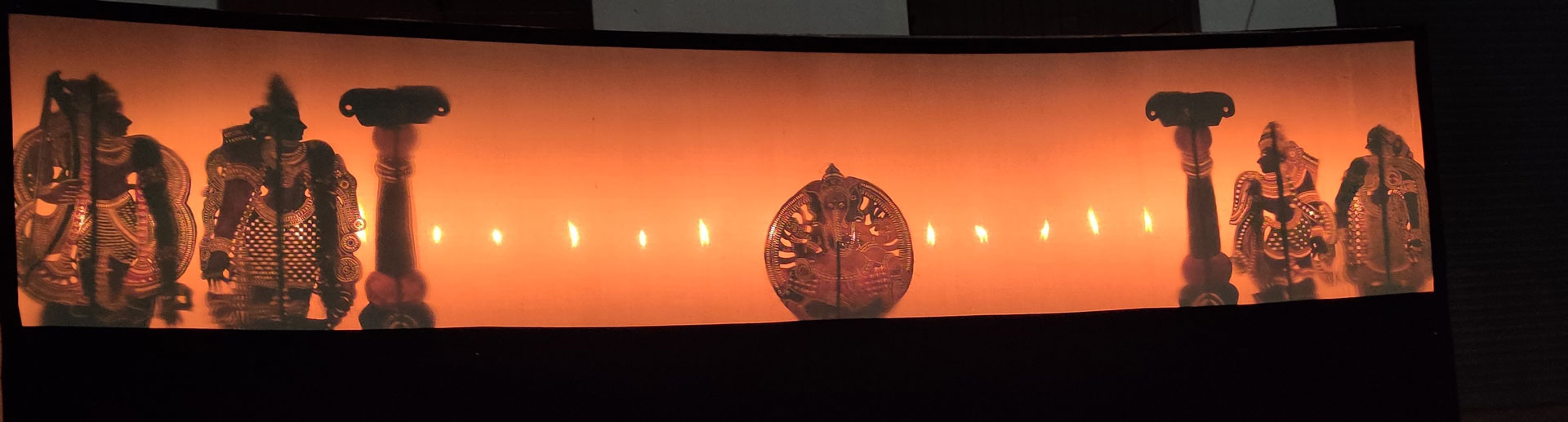

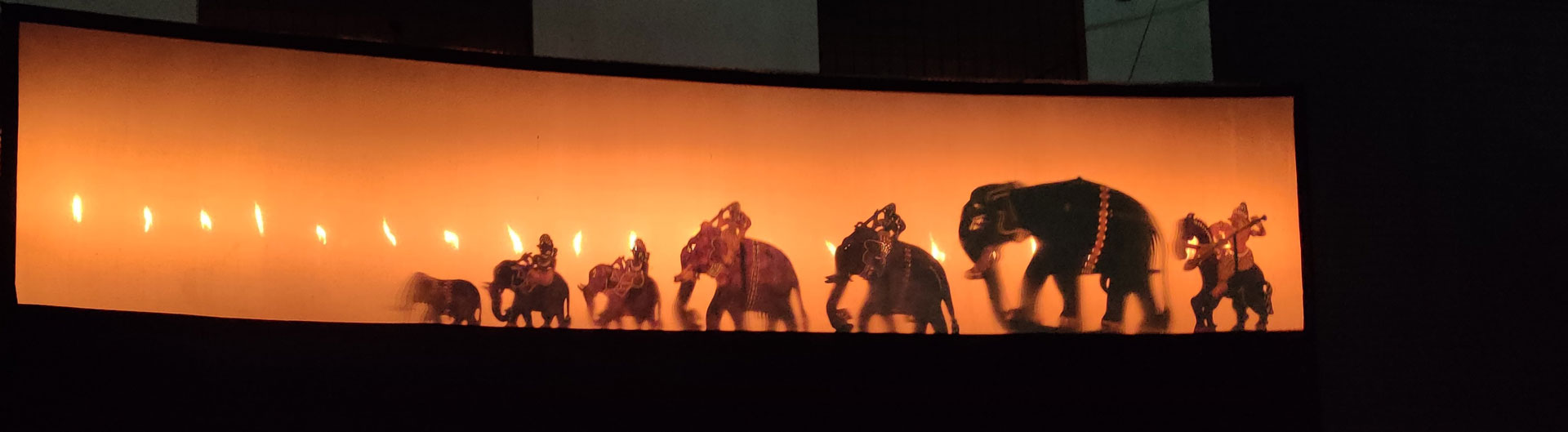

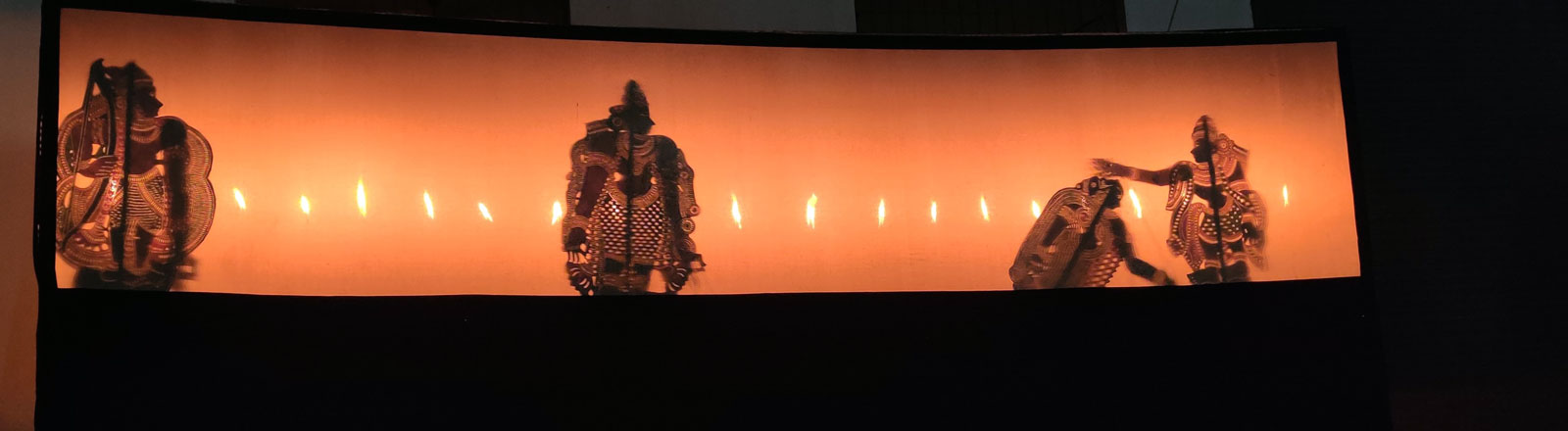

Tholpavakoothu is a unique tradition of shadow puppet theatre from central Kerala in present-day India. The word Tholpavakoothu is a combination of the Tamil terms, that is, thol meaning leather, pava meaning doll and koothu meaning play. The art form is mainly described as a performance ritually conducted using leather puppets for goddess Bhadrakali in permanent theatres called koothumadams. Tholpavakoothu artists started using Kamba Ramayana by the poet Kambar as its basic text after its 28 adaptations by puppeteer Chinnathampi Vadhyar in 12th century CE. Before Kambar’s text gained popularity, Tamil folk stories like Nallathangal, Harishchandran nadagam, and others were famous and used in the shadow puppet performances.

Origin

The art form begins with groups of Tamil itinerant performers usually belonging to Vellalachetti and Nair castes who travelled and performed popular Tamil folk tales through the medium of shadow puppetry along the river Bharatappuzha. Ramachandra Pulavar believed that “in its present form with stories from the Ramayana, Tholpavakoothu goes back 1200 years and began in the 9th or 10th century,” a belief also iterated by his father master puppeteer Krishnan Kutty Pulavar. Comprehensive information on Tholpavakoothu has been compiled in various works in the 20th-century studies of the art form. The 1943 work ‘The Shadow Play in Malabar’ was one of the first comprehensive articles exclusively about Tholpavakoothu.

Invocations at the beginning of every performance names the first two generations of performers to adapt the Kamba Ramayana text by poet Kambar for shadow puppetry performance. - G. Venu, Sangeet Natak Academi 1990

Towards Contemporary Forms

According to Puppeteer Rajeev Pulavar, “The support of the Kavalappara King in bringing artistic innovations to the Tholpavakoothu practices in the late 18th century was one of the first trends of modernisation of the art form.” Despite this, the loss of royal patronage severely affected the puppeteers. Master puppeteer Ramachandra Pulavar says that “the Tholpavakoothu traditions continued and were even promoted by the British rulers.” There is a general lack of references to shadow puppetry during the colonial period as it remained largely localised and attached to its older ritualistic temple settings. The 1970 Land Reforms Act in Kerala ended the feudal system, causing a big decline in donations to artists. By 1972, only 63 temples hosted active Tholpavakoothu performances, down from over 100 earlier. As patronage dropped, so did the quality of performances and knowledge transfer. Younger generations sought permanent jobs over the unstable income from seasonal performances

In addition, from the late 60s, the socio-economic factors of the art form began to be discussed in the literature on the shadow puppet traditions. The late master puppeteer Krishnan Kutty Pulavar of the Koonathara troupe himself published two studies, one in English and one in Malayalam. The Malayalam language work Tolpavakoothu – The Traditional Shadow puppet play of Kerala, vol-1, Balakandam, published in 1987 was based on the story of the birth of Rama from palm leaf manuscripts. In the 1990s, short, comprehensive guides to the art form started cropping up post which studied the effects of the changing socio-economic environments of Kerala on the art form and lives of the artists also can be noted. The modern literature on Tholpavakoothu attempts to look at the artist’s strategies to continue the practice of art form.

A Continuing Tradition

The art form traditionally places importance on the ancestry of the performers as there are palm leaf texts with verses that pay homage to old teachers as suggested by one of the oldest living puppeteers Annamalai Pulavar, and pays tribute to these old teachers in invocations sung at the beginning of the performances. The puppeteers of the Kavalappara troupe, puppeteer Rajeev Pulavar stated that “we can trace about 8 of their ancestors performing Tholpavakoothu.” He added that researchers have traced 13 generations of their traditional family who have been performing this ritualistic art form. This makes Rajeev Pulavar and his brother Rahul Pulavar, part of the 14th generation as their father, the master puppeteer Ramachandra Pulavar part of the 13th generation of traditional performers

The artists of the Koonathara troupe manage their ritualistic practices and understand the importance of maintaining and passing down the customs they need to perform as Pulavars. Ramachandra Pulavar mentions that “the art form is the result of years of flow of emotions, beliefs, and art and that the flow is not limited to the boundaries of heredity or old rituals. We believe in the journey of the art form as sailing forward in the present, adapting to changes and newness with new aspirations and hopes for the further growth of the art form". He also highlighted a symbiotic relationship between the practice of the art form and the people when he said that, ‘the rituals of Tholpavakoothu are the beliefs of the people’.

An Approach to Innovation

It was in the 20th century that Tholpavakoothu saw the next phase of some of its most significant documented changes. Performing arts change with changing social environments and patronage patterns. Tholpavakoothu has modernised uniquely compared to other shadow puppet traditions in southern India. Ramachandra Pulavar and the entire Kavalappara-Koonathara troupe have immense respect and gratitude for master puppeteer KK Pulavar. They commend him as at that time, he was courageous enough to take the art form out of its religious context and onto a stage and appropriate the art form in various ways to fit into this new format and context.

“My father KK Pulavar believed that changes can and should be brought to the art form to continue it. That is why when Tholpavakoothu witnessed declining audiences, no other artist group except for the Koonathara troupe, was willing to deviate from the traditional practices”- Ramachandra Pulavar, 2020

Koonathara troupe believes that modern cinema developed from Tholpavakoothu as they related the modern film theatre to the koothumadam. They focused on innovating and reimagining the art form for changing times. The Koonathara puppeteers made their first shadow play show based on a narrative other than the Ramayana. The story they used was from Panchatantra, a collection of stories consisting of animal characters giving moral values lessons from ancient India. The performances themselves now take on shorter compressed formats of 1-2 hours, with faster narratives. Pre-recorded music, and commentary to cater to modern attention spans. Modern puppeteers recognized the need in today’s socio-economic environment to create and represent diverse stories in many languages to connect with varied audiences and create opportunities in many new avenues for the art form to expand, as well as rebuild a strong base in the art form’s original locale.

Materials and Modifications

The puppets used in Tholpavakoothu are made from deerskin and prepared using traditional methods like water, ash, and natural dyes. They are categorized based on postures and meticulously crafted to depict various characters and scenes from the Ramayana. The performance, conducted in dedicated theatres (koothumadam), involves elaborate rituals and musical accompaniments. The ritualistic performances are conducted from January to May, followed by a structured format that includes prayers, lighting of lamps, and recitations of sacred verses. The puppeteers, known as Pulavars, play a central role in the performance by manipulating the puppets

Mythology entered and assimilated into the traditional trajectory of Tholpavakoothu at some point after the 12th Century because Kambar lived, worked, and wrote the 11,000 stanzas of Kamba Ramayanam in the 12th century C.E. This was the most prominent change that occurred in the ‘tradition’ of Tholpavakoothu, as Kamba Ramayan changed the course of the art form for generations that followed. Although changes and modifications are not normally considered part of that which is ‘traditional’, a traditional art form like Tholpavakoothu, even in its pre-modern era was open to innovations, modifications, and improvisations and was changing in its way.

“In the process of innovation and expanding the art form, there were both successes and failures.” - Rahul Pulavar, 2020

The 1990s-2000s period of globalization caused confusion, as the local context underlying traditional arts changed rapidly. The spread of consumer culture and capitalistic value systems caused a decline in local engagement of art forms like Tholpavakoothu. Following this, the new millennium was characterised by a significant innovation made by the Tholpavakoothu artists. For the Panchatantra narrative, the puppeteers made use of their traditional animal puppets. This gave the troupe more chances to perform in schools and other venues.

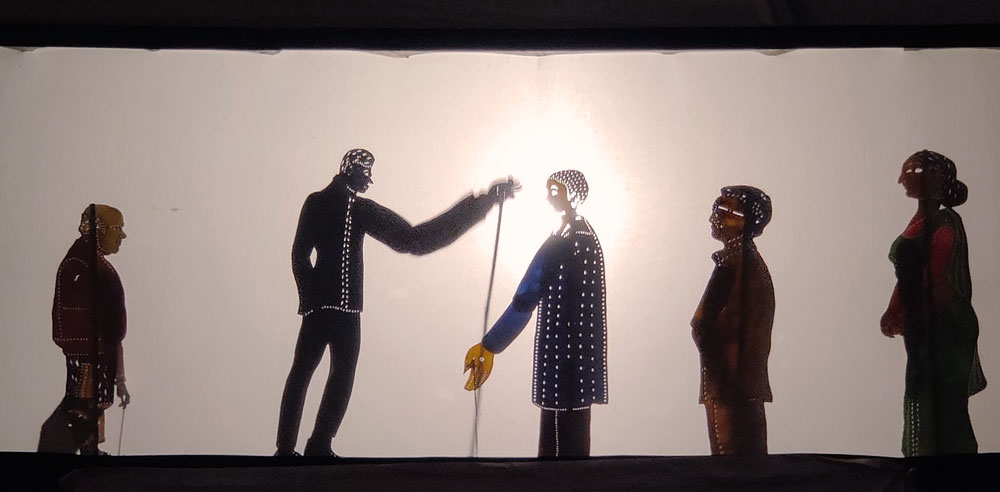

In 2007, the Koonathara troupe further experimented by using the theme of Mahatma Gandhi’s life and appropriating it for a Tholpavakoothu play. In this, the puppeteers experimented with the creation of appropriate puppets like automobiles, weapons, modern clothing, etc. This was their first project in which they dealt with a text that was not mythical but, historical. In 2012, the Koonathara troupe created a play based on the story of Jesus Christ to connect with Kerala’s Christian population, and have also occasionally adapted Muslim Arabic stories, forging a new multi-cultural identity for the art.

“2010 is the year when the troupe once again began to create and release processed works. It was a period filled with experimentation for the artists and art forms to adapt to the ever-changing society." - Rahul Pulavar, 2020

The puppeteers have collaborated on artistic projects featuring Shakespearean narratives and have had Tholpavakoothu puppets featured in music videos and as the logo for Kerala's International Film Festival in 2021. They have leveraged the internet and social media, creating online profiles, websites, and YouTube channels to promote and share videos of their performances. In response to COVID-19, with their livelihoods at risk and limited skills outside their art, the Koonathara troupe navigated the pandemic's restrictions by embracing digital platforms. They created an awareness campaign video, shared widely on social media, and conducted online performances via Zoom, including a special Ramayana performance in English

Present status

Krishnan Kutty Pulavar identified the declining audiences, loss of patronage, and a level of ambiguity in the future of artists. Identifying this, the Koonathara troupe began to make changes that were later seen as revolutionary. Due to such changes, there was a loss in the traditional ways of preparation and of puppets, and the art was only passed on and retained by a few puppeteers like Krishnan Kutty Pulavar and his sons, i.e. the Koonathara (Kavalappara) troupe.

Kerala faced significant challenges due to consecutive floods in 2018 and 2019. The Shoranur area, where the Koonathara troupe of Tholpavakoothu resides, was also impacted, disrupting basic amenities like transportation. The situation worsened with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The peak performance season for Tholpavakoothu, from January to May coincided with the lockdown, leading to the cancellation of temple festivals and performances, resulting in a significant loss of income for the artists. With their livelihoods at risk and limited skills outside their art, the troupe struggled to navigate the pandemic’s restrictions. The troupe also utilised the lockdown period to deepen their knowledge of traditional texts and train younger puppeteers, though the financial struggles remained a pressing concern. The troupe’s efforts to adapt to the digital age by sharing their art through new media platforms demonstrated their resilience and commitment to preserving Tholpavakoothu.

The changes in the art form have not been linear in the way that the modernisation of the art form weakened the traditions, or the tradition curbed from innovating the art form. Tholpavakoothu continues to draw audiences due to this very attitude of the artists of the Koonathara troupe and other practitioners of the art form. Indian news houses like The Hindu have used language like “Shadow of death over Tholpavakoothu” (June 23, 2003), and “Shadow leather puppet play facing near death” (May 12, 2010), to portray a sort of perception that the art form is dying. And that the only thing the outsiders can do is to attempt to understand the reasons behind the way the art form grows or declines.

On the other hand, in today’s scenario, the puppeteers of the Koonathara troupe say that the art form is indeed ‘developing’ and ‘growing’ as their efforts are ongoing. The life of an ancient art form such as Tholpavakoothu cannot be described in merely linear timelines. From being a nomadic art form to being only temple-bound to now being a stage-diverse and ritualistic art form, the art form and its artists have adapted to a fair share of changes.