Untold stories from Anchuthengu (Anjengo)

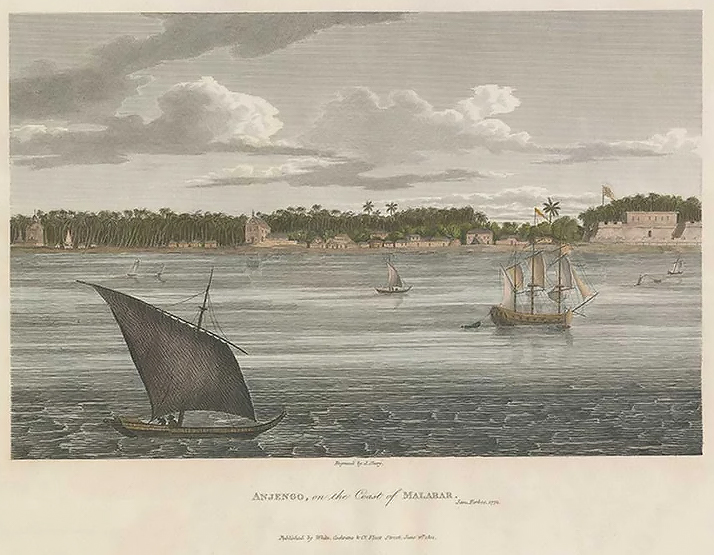

Anchuthengu is a coastal village northwest of Thiruvananthapuram on a sandy isthmus between the sea on the west and the backwaters on the east.

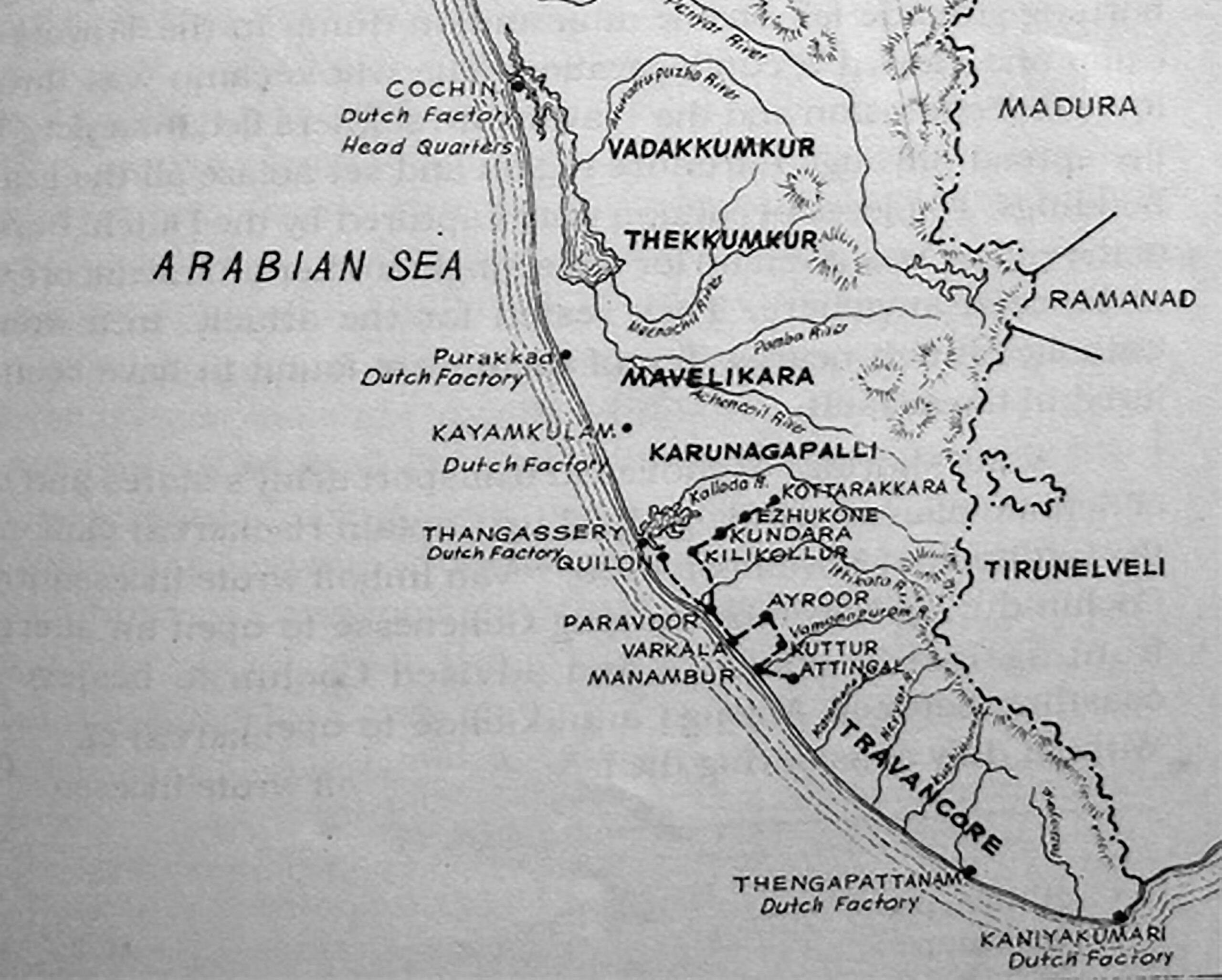

During the 17th century, the Rani of Attingal controlled this area, which was known for its pepper lands. In 1684, the Rani permitted the English to establish a factory. The Dutch and the English had a growing rivalry, and in 1694, the English began to construct a fort to control the pepper trade in the Attingal region. The fort’s construction was delayed for a few years due to Dutch demand for an exclusive monopoly on the pepper trade. Despite a blockade by the Attingal army and an attack by them, the English defeated the Attingal army in 1697. Finally, the English agreed to pay an annual rent and the fort at Anjengo was completed around 1698-99.

The Fort at Anjengo

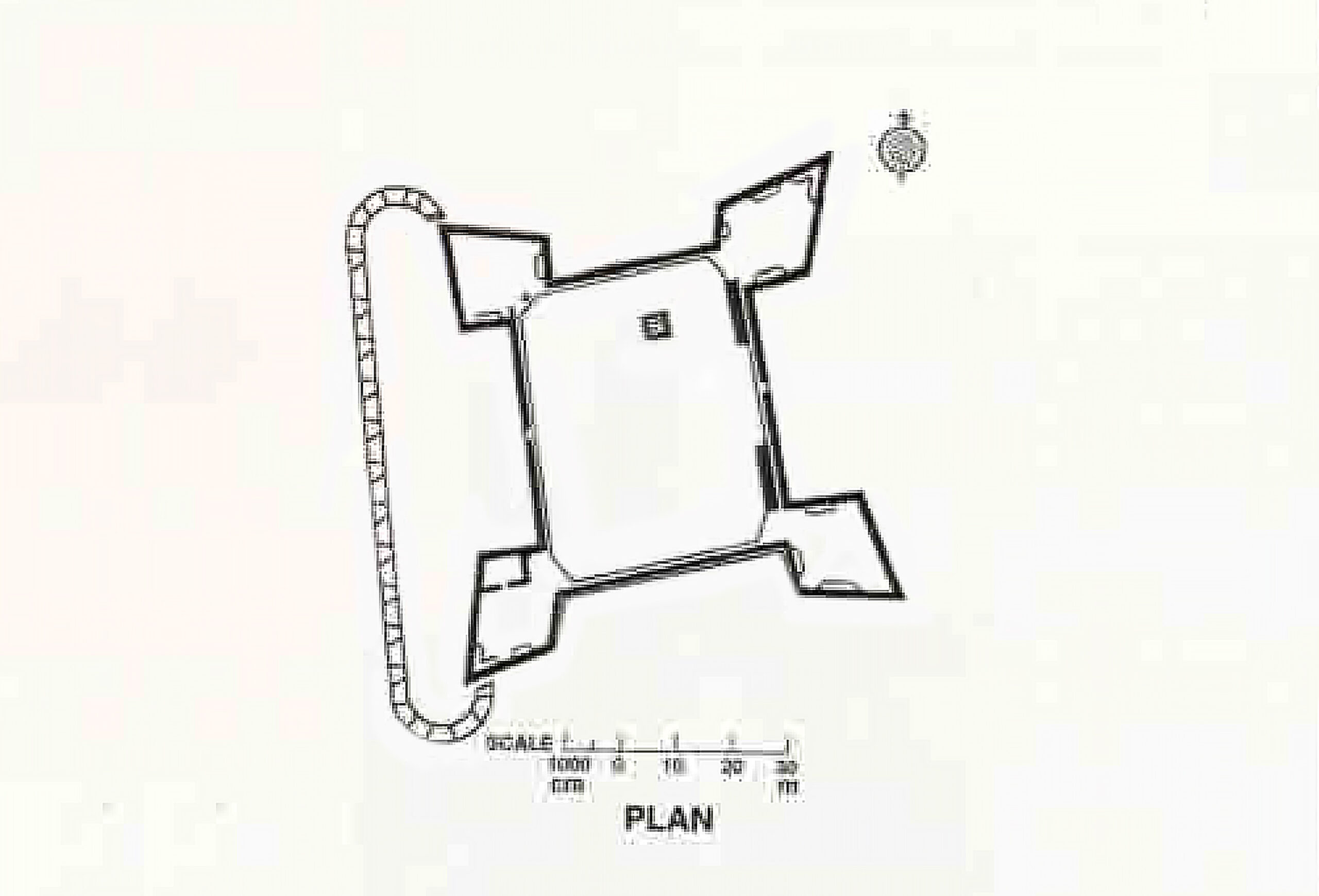

The shape, size, and design of the Anjengo Fort were quite different from other structures built around that time. It had two entrances—one east towards the river (backwater) and another west (facing the sea). Surrounded by high laterite walls, the fort served as a military armoury during its active years, while the laterite is now invisible as it is covered by lime plaster.

An important feature of the fort is the lookout points or bastions, set to give a commanding view over the surrounding land and sea. Each of the four bastions mounted eight guns, while an equal number were placed between them. The jetty and landing stage were approached from the gates on the east and west and could also be easily defended by the fort gun batteries.

The fort could house about 400 soldiers and was built to secure the well, the surrounding area used by the warehouses, and some dwellings of the English. On the west (sea-facing) side of the fort, one can see seven stone pillars and the base of three others outside the walls. The English used these to bind and punish prisoners and slaves. The low archway made it difficult for attackers to enter the fort.

The Tunnel

Various legends about the tunnel exist, but it is clear that it was intended for those inside the Fort to escape by sea. Two decades ago, workers encountered a tunnel emerging from the Fort while constructing a well at a nearby house between the Fort and the sea. The tunnel was closed so that the well could be dug further.

“I had seen the tunnel inside the Fort before it was closed. It was pitch dark, and steps went down to the tunnel. I could hear the sound of waves on the shore. It was walled up a few decades ago.”

-Nelson, 70, a worker at the Fort, 2024

The Well

Surrounded by sea and brackish backwater, Anjengo island has a shortage of fresh water. The value of the well could be judged by the fact that the English built the Fort around it so that they could control it even if they were under attack.

“The only perennial source of fresh water in Anchuthengu is the well inside Anjengo Fort. Villagers come here during water shortages when other modern sources (piped water and tanks) dry up.

-Nelson, 70, a worker at the Fort, 2024

The Light Mast

The old light mast built of teak wood had a lantern at the top to guide ships at sea and acted as a signalling station for ships arriving from Britain. It was replaced in 1988 by a new 125-foot-high lighthouse ten meters from the Fort. However, the new lighthouse remains shorter than the teak wood light mast when it was in use.

“I was a daily worker when the new lighthouse outside the Fort was built 40 years ago on the bastion inside the walls. It was a massive structure with a lantern on top, and was supported by two clamps on the side, which are still visible.”

-Nelson, 70, a worker at the Fort, 2024

Not an Easy Life

Life in the East India Company (EIC) forts and outposts was isolating for the English men and women. Unfamiliar climate and disease took a toll, and many died young. The major attraction for English volunteers to come to India was to make a fortune. EIC officials were paid a small salary, but were allowed to trade privately using company ships and warehouses.

As personal trading for money-making utilised company resources, it became entangled with the East India Company’s affairs. For these reasons, John Kyffin, the chief of the factory at Anjengo, refused to leave his post. Instead, he spread rumours that the political chief, Gyfford, used his beautiful wife to achieve his ends.

On April 11, 1721, during Vishu, William Gyfford and Anjengo’s officers visited the Rani of Attingal with annual gifts. That evening, 140 Englishmen from the group were slain at the river to the Rani’s Palace. A few Topasses escaped and informed the fort dwellers of the ‘Attingal Massacre’. Samuel Ince, the chief gunner, defended Anjengo Fort with the survivors, stocking it with essentials. The Attingal nobility later attacked the Fort, causing extensive damage, but failed to seize it. Reinforcements from Thalassery arrived in October 1721, relieving Anjengo Fort after six months of turmoil.

Military Backbone

Marthanda Varma’s wars of conquest forced him to seek the assistance of the English settlement at Anjengo for the supply of arms. In 1742, he visited the English at Anjengo and succeeded in obtaining several pieces of heavy artillery, 150 soldiers, 500 guns, and six barrels of gunpowder for the Travancore Army. The army and European-style cavalry and infantry were trained on the grounds outside the fort. During the wars of the Carnatic, it was used as a depot for military stores. In 1759, when Yusuf Khan attacked Puli Tevar’s territory with the help of Travancore troops, they received fresh military supplies from Anjengo. The Fort played an important role in the Anglo–Mysore wars (1798-99), as it was used to store ammunition for the British.

Deactivating the Fort

The fall of Mysore to the English East India Company in 1800 resulted in the signing of the Subsidiary Alliance with Travancore, which placed Travancore under the control of the English. Anjengo Fort, its troops, guns, and armoury had greatly affected this alliance. A struggle for power between the political and commercial chiefs of Anjengo had begun, but the declining pepper trade led to the post of the commercial chief being abolished.

In 1809, the disturbances in Travancore led to Anjengo being blockaded. Hence, the factory was closed the next year, and with diminished military usefulness, Anjengo was transferred to the English Resident at the Travancore Court and the Fort was abandoned in 1813.

Anchuthengu Today

St. Peter’s Forane Church near the Fort was constructed 400 years ago by the Portuguese, and in a recent renovation, tombstones of Portuguese and English officers and priests were discovered beneath the church.

A Dutch trading ship, ‘Wimmenum’, built in 1752 at the Dutch East Indian Company Wharf in Amsterdam, was recently discovered by scuba divers at Anchuthengu. It is said to have sunk around 1754, after being attacked by ‘Angrians of the Malabar coast’.

Anchuthengu is a fishing village with a continuous history of awareness and resistance. In November 1993, a much-publicised conflict occurred between the traditional fisherfolk and owners of mechanised boats or trawlers over fishing rights in the sea. It has taken a long and painful struggle for workers to resolve this, leading to some kind of balance between the traditional and mechanised workers today.