Vernacular Architecture – A Connection between Kerala and South East Asia

Why does the Kerala parotta have a parallel existence as the national food of Malaysia? How did Parashu Rama, the sage who threw an axe and created Kerala, become the main antagonist in a Cambodian classical dance?

These are a few of the connections between the worlds of Kerala and Southeast Asia. This exhibition describes how architectural traditions also illustrate unexpected links between them.

Vernacular Architecture

Kerala and most of Southeast Asia fall under the same tropical climate belt. Both share a hot, humid climate with periodic rainfall and are surrounded by dense jungles. As a result, the two regions share similar challenges.

While the sloping pyramidal roofs help with the heavy rainfall, the eaves stop glaring sunlight from entering the house. The uneven texture of the exterior walls helps ensure self-shading. The open layout typology with minimum furniture and transitional space between the exterior and interior underlies the sweeping emphasis on transparency and openness that unites both building styles. The abundance of land also allowed the building of houses in the centre of large plots. This served to allow sufficient wind flow, easing the humid climate.

Beyond a common wet tropical environment, geography is also a factor when building houses.

Minangkabau in the highlands of Indonesia is exposed to frequent environmental hazards in the form of floods, fires, and earthquakes. This explains the flexible and light character of the buildings of Indonesia in contrast to the rigid architecture of Kerala.

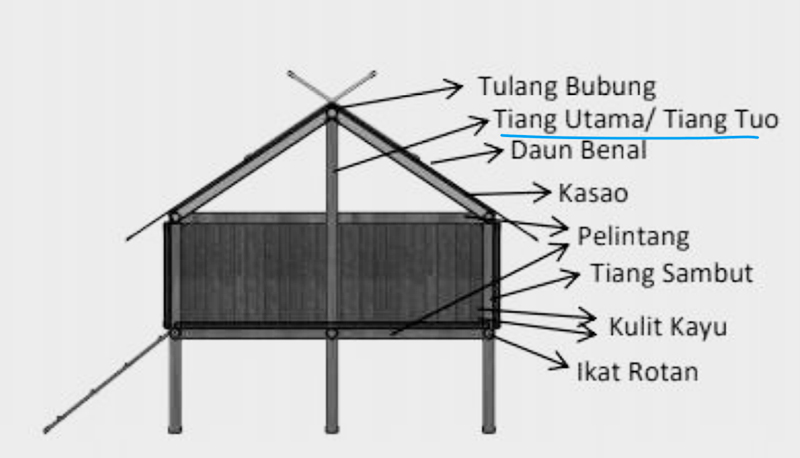

Tiang Tuo (old pole), a sacred symbol of protection in Minangkabau, in addition to its ritual significance, also serves as the central post of the building and makes it earthquake-resistant. Its counterpart in Kerala, the arudham (annular beams), solely serves a ritual purpose.

Most openings in a typical Kerala courtyard house are concentrated in the interior, especially towards the courtyard. This serves two purposes:

- First, to facilitate air circulation and take in less radiation.

- Two, the courtyard in Kerala houses is traditionally reserved for the deva sthana, the sacred dwelling of the gods.

In the rest of India, the kitchen or the agnikon (fire corner) is built southwest of the house. In Kerala, kitchens are built in the northeast corner, i.e., the most auspicious part of the house.

A practical reason behind this was to maintain a smoke-free interior. Since the main wind current in the region was from the southwest. Bali, in Indonesia, follows a similar hierarchical ordering of the spacing, with the value descending from the northeast corner to the southwest corner.

Form and Material

Saddle-shaped roofs are common in both Kerala and Southeast Asia. Scholars consider this roof construction and its wooden structure a natural progression from the early bamboo houses.

Besides, in Kerala, 50 per cent of the roofs were made from coconut or palm leaves. Beyond its cheapness, this natural material with numerous cavities ensures temperature and sound insulation.

Building materials were selected based on local availability. Before the 19th century, traditional buildings in northern Kerala were built of laterite and stone, which were easily available. In contrast, the ones in south Kerala were made entirely of wood, especially timber.

Livelihood Connections

A long coastal line, wet paddy-farming traditions, and reliance on canals meant the households underwent modifications to fit in with the owner’s line of work.

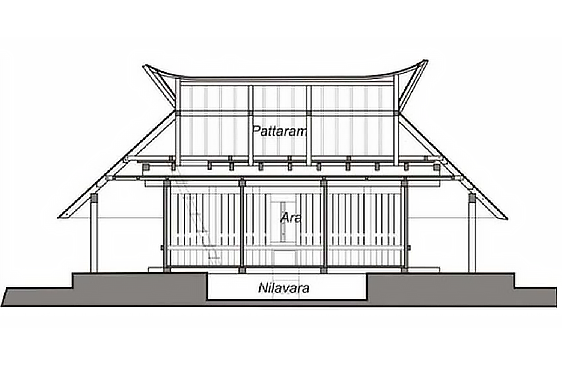

One of the common structures in residential buildings in Kerala, the ara (grain storage), where the bulk of the agricultural produce was stored, was considered the most auspicious part of the house. Within Kerala, the location of the ara underwent regional variations. While most granaries in Travancore were attached to the kitchen and/or built underground, they were placed outside the main house in north Kerala.

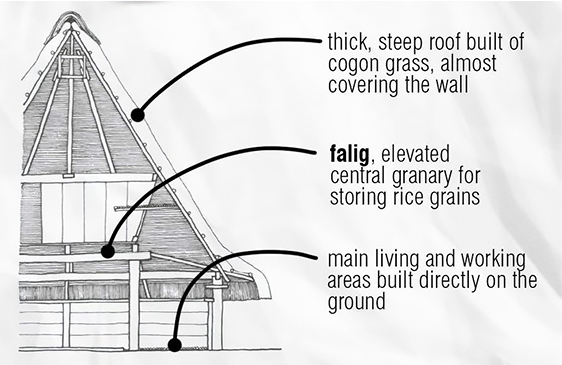

The granary house in Kerala shares a spatial-structural resemblance to the Bontoc houses in the Philippines and the Sunda area of Indonesia. Both are built as raised structures. While the space below the granary was also used as storage (nilavara) in Kerala, the Bontoc people lived beneath the granary.

Architectural Techniques

Experts deem Kerala a “real conservatory of the ancient carpentry of southern Asia,” so much so that the architecture treatise is called Thachu Sasthram, or the carpenter’s science.

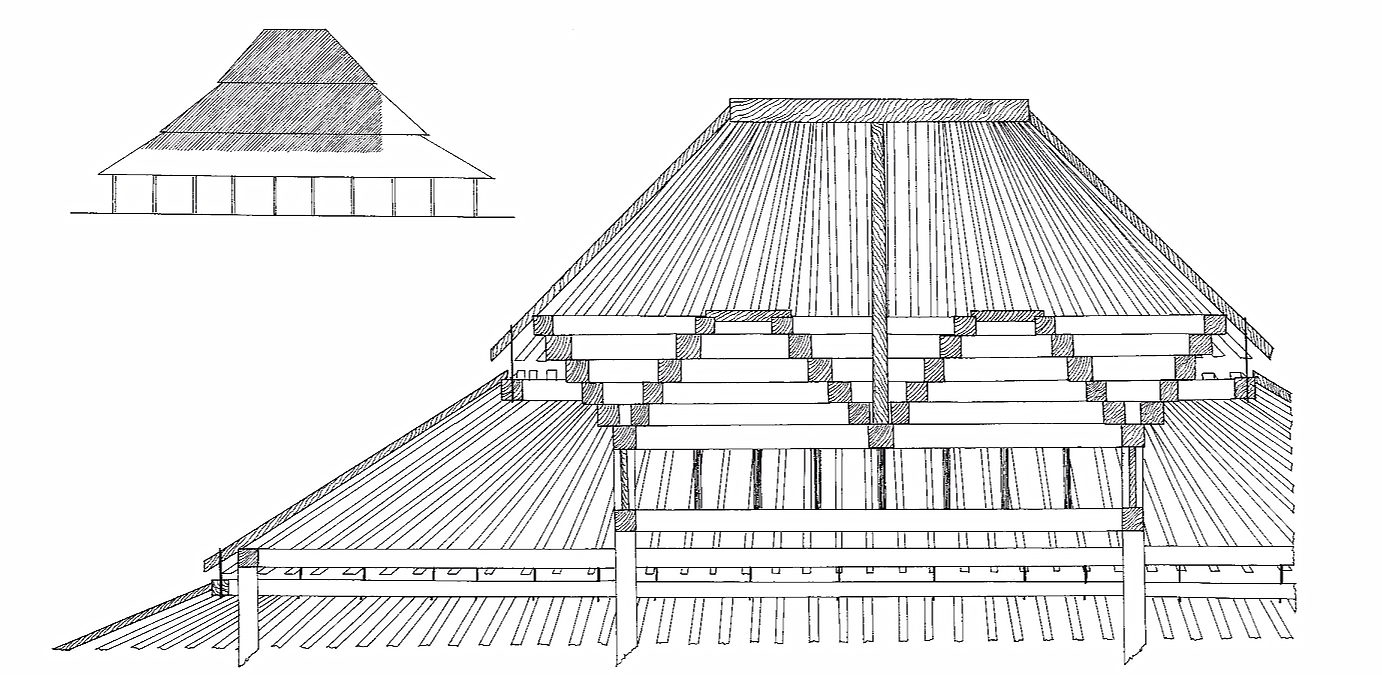

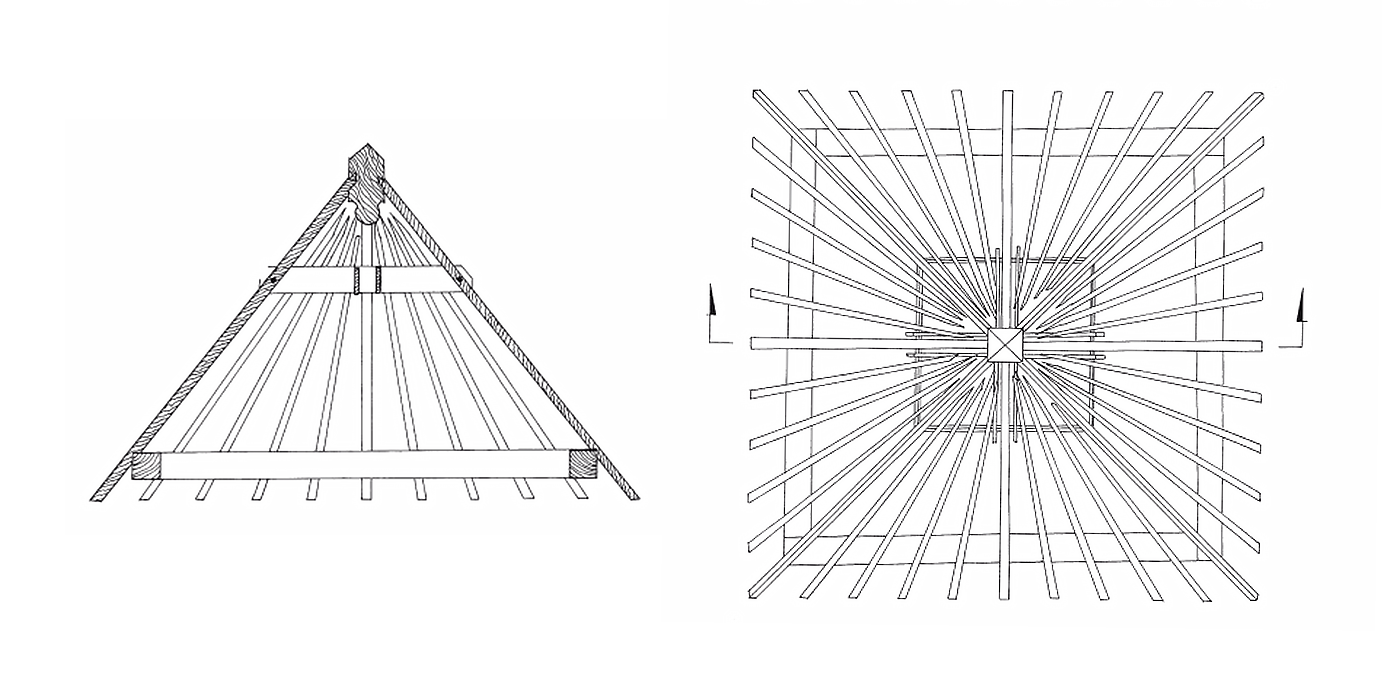

Regarding roofing, Kerala is the only remaining place in South Asia that has the stacking of beams roofing technique. However, one of the disadvantages of using bending frames is that the interior appears cluttered. Yet, this technique is widely used in Kerala. Builders overcome the limitation by introducing horizontal framing that prevents rafters from bending and allows for a large space in the interior.

The radiating framework is also visible in Java, Bali, and Lombok. It is characteristically visible in the Javenese, Pendopo. Another variation is still used for small sanctuaries in Kerala but is hard to find elsewhere in India. This roofing structure involves a hip roof on one side and a gable on the other, supported by screeds. To the east of the subcontinent, this technique is popular in Cambodia.

Sacred Architecture

- Buddhist Temples

The possibility of Buddhism entering Kerala through the west coast from Sri Lanka cannot be ruled out. Similarities between the Buddha images of Anuradhapura style (Sri Lanka) and a 7–8th CE image of Buddha found at Marudurkulangarai, near Thiruvananthapuram, are a testament to this fact.

The preexisting circular shrines of Kerala also seemed to have undergone modification upon the arrival of Buddhist missionaries/Ilavas from Sri Lanka, as the vatadage (Buddhist circular shrines) is identical to the Kerala circular shrines with rows of pillars surrounding the garbhagriha in the centre. The geographical proximity and political influences between Kerala and Sri Lanka, especially the migration of the Ilavar or Tiyar, make the above assumptions highly probable.

Stella Kramscrich, however, traces a few other influences to the circular shrines from within Kerala. Ullathas (a caste group) practice a marital tradition where the bride-to-be chooses her husband while shut in a large round building made of leaves. The conical huts of indigenous groups like Malapantarams are another example.

2. Islamic Styles

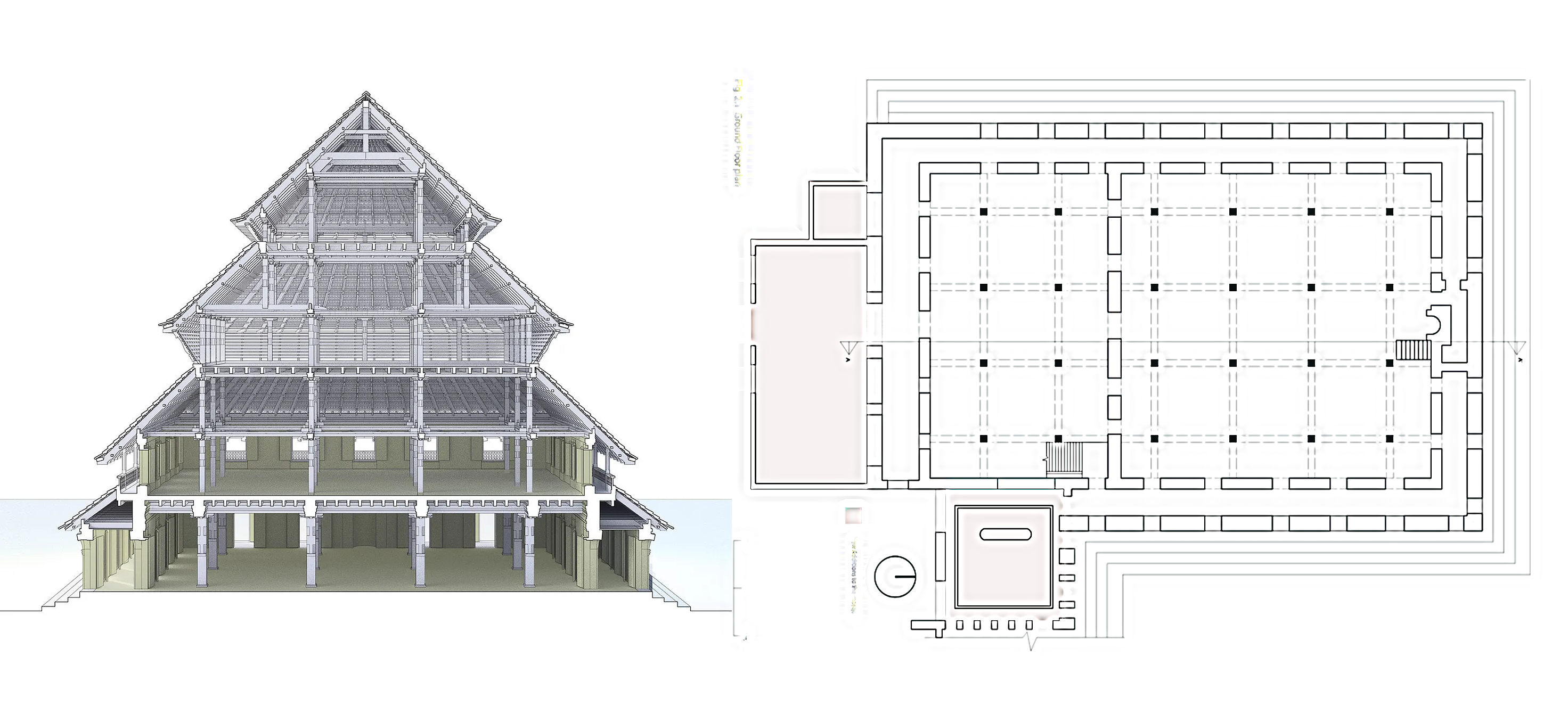

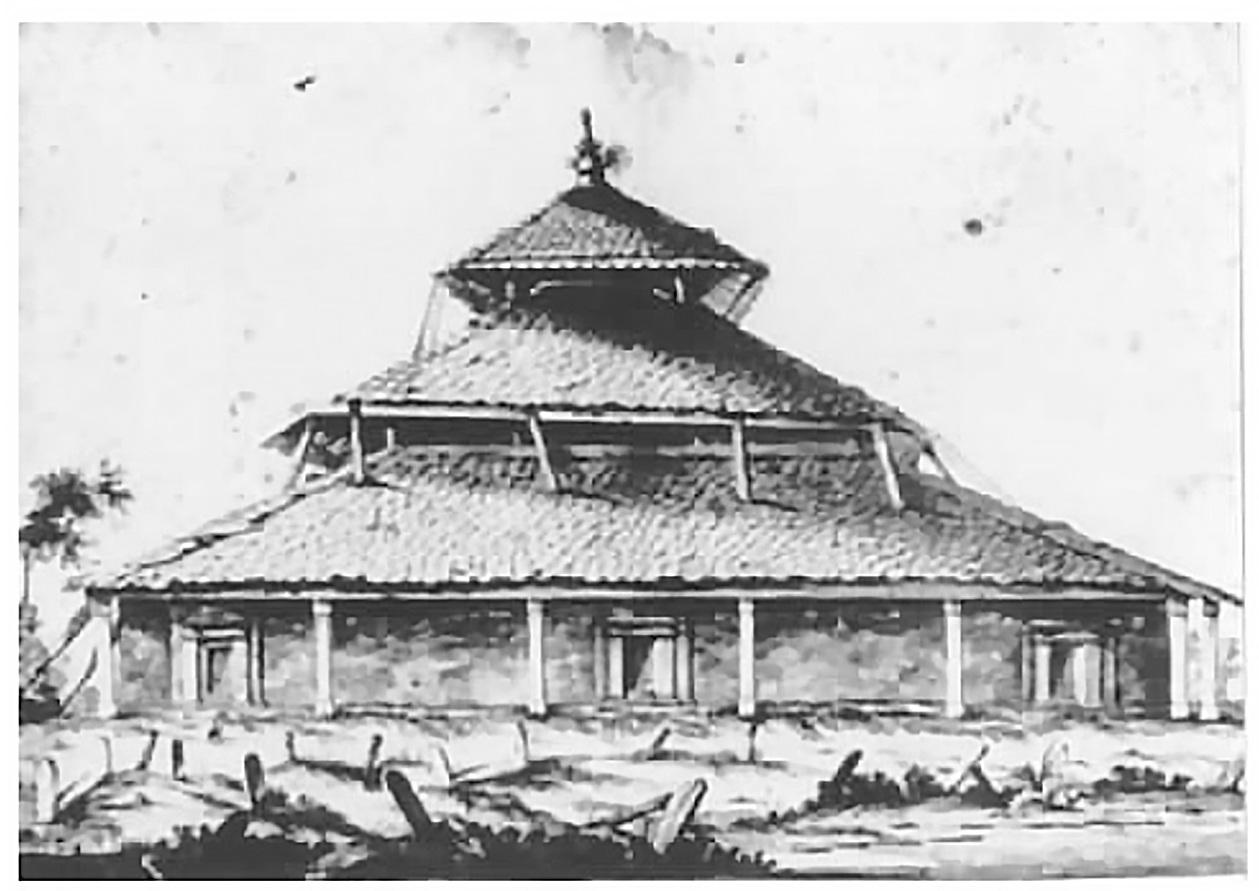

In principle, the mosques of Kerala have a wooden upper storey with sloping roofs on stone foundations. Built as three-tiered structures, the ground floor is reserved for praying, and the upper floors function as madrasas, administrative offices, or store rooms, with an antechamber that precedes the prayer hall. Besides the wooden roof, the colonnades surrounding the prayer hall found in Southeast Asian mosques are defining characteristics of Malabar mosques.

The oldest mosque in Indonesia, Agung Demak, shares the above similarities with mosques in Kochi and Kozhikode. In addition, the wooden colonnades serve as the lower tier of the roof of the building. Mehrdad Shokoohy notes Agung Demak’s “thick masonry walls, three entrances on the eastern wall and a single mihrab in the form of a deep niche, projected outside the qibla wall” to bear resemblances to the mosques of Kerala. Besides, the layout of the mosque is very similar to the Cheraman Juma Masjid in Kodungallur, Kerala.

In the interior, the roof-like wooden canopy used as the speaker’s platform and the floral patterns on the minbars of the two regions are specimens of craftsmanship and differ from the stone and wooden minbars of North India, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Kerala and Southeast Asia differ from North Indian and Middle Eastern Islamic traditions. The mosques are devoid of arches, domes, minarets, and geometric patterns that mark the visual identity of Indo-Islamic architecture in north India.

Socio-political Impacts

In the 16th century, the Vijayanagar empire’s fall caused Brahmin migration to Kerala. These Tamil-Tulu Brahmins settled around temples in colonies called agraharams, which have rows of houses built linearly with shared walls and long connected verandas/corridors (puramthinna). Though common elsewhere in India, row houses are an anomaly in Kerala. The single-detached houses with open spaces on all four sides were the norm in Kerala.

Colonial rule introduced new elements and styles. The shared Dutch colonial past of Kerala and Indonesia explains the resemblance between the design of Bolgatty Palace (1774), a traditional pathya pura (granary) in Piravom, and a hall in THS de Bandoeng Indonesia (1920).

Later, with the British too, a highly localised architectural style emerged called Travancore-Victorian architecture. While the projecting gables (mukhappu) were retained, the tiled angle brackets above the windows were a new addition. In the native bungalows, staircases were built in the interior, while the British bungalows featured wooden exterior staircases.