The Essence of Rubber Production

Studies trace the introduction of the non-native rubber plant in Kerala and India, back to the early twentieth century when the British supplanted the indigenous Indian Rubber tree (Ficus Elastica) with the superior Hevea Brasiliensis.

Often dubbed the Para rubber tree, owing to its connection with the Brazilian port of Para, this species boasts rapid growth and a straight trunk enveloped in thick, relatively soft bark.

In India, the Para rubber tree follows a deciduous pattern, entering dormancy from December to February. Nevertheless, it swiftly regains foliage and bursts into abundant flowering thereafter. Each fruit of the rubber tree bears three lobes, each containing three oil-rich seeds.

Despite its potential longevity of a century or more, the economic viability of rubber tree plantations typically spans around 32 years. Commencing its journey as a sapling, it undergoes a seven-year initial phase of immaturity succeeded by 25 years of productive growth.

The Early Growth Stage

This photo introduces us to a rubber plant that has reached the tender age of two years with a slender trunk of a few inches in girth. Standing tall at a remarkable height of 9 feet, the tenacious rubber plant’s branches already carry lush green leaves that will gradually transition to a dignified brown hue.

Maturity and Productivity

Notice the precision with which the rubber planter has meticulously organised the plantation.

Not yet fully mature, the rubber farmer has yet to commence the tapping process, which elicits the invaluable latex that serves as the foundation of the rubber industry. Deliberately planted with a spacing of 10 feet between each tree, a strategic arrangement becomes evident, allowing ample room for each tree to thrive and flourish.

Fully Grown Trees

A fully grown rubber tree trunk, waiting to be tapped, boasts an impressive diameter of 20 inches and presents a unique interplay of colours with distinctive white spots on a light greenish-brown trunk.

“Just getting to age seven is not important. Being the right size and being healthy enough to be tapped by the time the tree is seven is important. If the tree trunk is not twenty inches by the time it is seven, we will have to wait till it reaches that size, which means we have to spend more before we start earning from the rubber”.

– Joy, a planter from Kottayam district, 2023.

When a leaf is plucked from a branch, the tree reflexively produces sap, characteristic of rubber trees where latex flows abundantly, regardless of the specific location where a cut is made.

The Tapping Process - Making the Cut

“Rubber trees are tapped early in the morning as that is when sap flows most freely”. – Haridas, 2023.

The cut entails removing a skinny layer of the bark, less than a centimetre wide, in a slanting manner. As time progresses, these cuts are strategically shifted above or below the original incision to ensure a consistent and uninterrupted flow of latex sap. Subsequent cuts are made immediately below the previous cut. The tapper makes cuts early in the morning as the lower temperature allows more sap to gather before it coagulates or has to be taken for processing. Second, this minimal approach enables sustainable extraction of latex.

Latex Collection

When a tree is first tapped, the cut is about four feet above the ground. Only one side of the tree is tapped at a time, with subsequent cuts made about a centimetre below the previous cut. The cuts on the tree in the picture have reached the bottom, and once this happens, that side of the tree is left to heal, and the other side starts to be cut. A side of a tree can be tapped for about eight years before switching to the other side. While one side is being tapped, the other side is left untouched. Each side can be tapped twice before the tree runs out of sap, and the planter decides to start something called a kadumvettu (called ‘slaughter’, in other places). In this case, every part of the tree is cut daily to extract as much sap as possible before it is cut down and sold.

The Cup

Here we shift our gaze to a crucial element of the rubber manufacturing process: the indispensable latex collection cup. Once made of used coconut shell, the cup is pivotal in capturing the precious sap derived from rubber trees. The size of these plastic cups may vary, contingent upon the tapping frequency of each tree. The cup pictured in this photo accommodates 600 millilitres of sap. In the market, one can typically find cups ranging from 600 millilitres to one litre in capacity. A metal ring holds the cup in optimal position to prevent latex from flowing to the ground.

Protecting the Latex

Moisture affects the drying time of rubber and leads to spoilage. Rubber farmers use plastic sheets to safeguard the cut and the sap-collecting cup from the unwelcome intrusion of rainwater. A bright green cover acts as a shield against water droplets entering the cup. Above this, a piece of white plastic sheet redirects rainwater from the trunk of the tree onto the green cover.

Alternate Methods to Cover the Cup

In some plantations, planters opt for a single sheet that fulfils the same purpose. While equally effective, this alternative approach offers the added advantages of convenience and efficiency.

The Process of Making Rubber

Rubber is made in three basic steps: collecting latex sap, adding water and formic acid, and drying the mixture for several hours.

Afterwards, rubber machines are utilised to eliminate moisture, with the second machine imparting a unique texture to the final rubber sheet.

Two approaches to drying the rubber sheets are used: exposing them to direct sunlight or subjecting them to smoke in an enclosed structure. Each method has advantages and limitations, with the smoking method expediting the drying process but requiring suitable structures.

The Rubber Shed

A rubber shed is a vital hub for the machinery processing latex sap. It is traditionally situated near rubber plants, within the plantations, or within the compounds of the plantation owners’ homes. Two rubber machines occupy the interior space of the shed. The shed is a space of convergence of manual labour and machinery, serving as a reminder of the continuous efforts made to improve productivity, ensure quality control, and meet the demands of a dynamic market.

“To set up a shed like this, one needs adequate space. It also does not make sense to build this if you are a small planter selling only a small number of rubber sheets. Why waste that space for a shed, then? It’s much easier to dry it in the sun”.

– Joy, plantation owner, Koothatukulam, 2023

The First Rubber Machine

First the mixture of latex, formic acid, and water are poured in trays and dried for three to four hours. The resulting latex sheet, still retaining traces of moisture, is fed into the first machine. This initial mechanical treatment is repeated several times to expel excess water content, enhancing the physical attributes of the rubber sheets, rendering them ready for sale.

The Second Rubber Machine

The second machine thins the rubber sheets further to build upon the initial moisture removal process. The sheets are gradually transformed into a more uniform thickness through controlled compression and stretching, ensuring consistency and optimal quality.

However, the journey does not conclude with the second machine. Additional drying methods include exposure to sunlight or utilising specialised drying sheds, after which the sheets are conducive to long-term storage and transportation. After fully depleting moisture, a rubber sheet weighs anywhere between 400 gms and one kilogram. The rubber sheets achieve market standards through these procedures and can then be utilised in an array of applications.

The Lever and The Wheel

The lever attached to the rubber machine demands consistent operation by experienced hands. It controls the wheel’s rotation, taking the rubber sheets through the rollers.

Feeding the sheets into the machine with one hand while operating the lever with the other requires practice. The synchronised action determines the rotational force of the rollers, which in turn regulates the texture and thickness of the rubber sheets.

Unused Machines

An unfortunate consequence of the plantation owner’s decision to refrain from tapping his rubber trees is that the rubber machine was left dormant for an extended period with wheels covered in green moss. The tarpaulin sheets carefully draped over the second set of machines are intentional, for the trees surrounding the machines are not mature enough to be tapped.

Rubber by Barrel

The once-enduring practice of making rubber sheets and subsequent drying techniques have regrettably fallen out of favour among many planters. The prevailing factor influencing this shift is the exorbitant expense associated with this approach. Given the persistently low rubber prices in the market, it has become more cost-effective for planters to forego the intricate sheet-making process altogether. Instead, they collect the latex sap in barrels to sell to rubber shops. This departure from the conventional method is an example of the pragmatic choices made by planters, adapting to the economic realities of the industry and a more viable approach to sustain their livelihoods.

Sale of Rubber Sheets

Various factors, such as the thickness, moisture content, and sometimes buyers’ specific requirements, influence the discrepancies in weight. The availability of rubber sheets with varying weights allows for a wide range of options, catering to the particular preferences and needs of customers in the market.

Rubber Scrap

Each day, as the sap is collected from the trees, remnants of dried latex are left behind in the cuts and latex cups are collected and sold separately without processing to rubber shops for use in small rubber products like rubber bands.

Natural Vs. Synthetic Rubber

Natural rubber, derived mainly from the Pará rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), possesses exceptional properties such as high tensile strength and rapid vulcanisation rate. It is preferred for various commercial applications, particularly in tyre manufacturing. Natural rubber is vulnerable to atmospheric elements and certain solvents despite its strengths.

Synthetic rubber, produced through different techniques, offer tailored properties to meet specific demands. It exhibits temperature and ageing resistance advantages, and its production is more cost-effective than natural rubber.

“That is made in big factories. It is not the rubber we get from rubber trees”.

– Roy, rubber shop owner, Koothattukulam, 2023.

The choice between natural and synthetic rubber depends on the intended application, as they have distinct properties and are not easily interchangeable. Their markets remain separate, with price disparities driven primarily by supply-side factors. The automotive sector significantly influences the demand and pricing of both rubber types, with natural rubber prices particularly susceptible to supply-side fluctuations.

Uncertainty in the Market

The natural rubber industry in India has been in a severe crisis since 2012, primarily due to a significant drop in rubber prices, rising production costs, and declining yields from ageing rubber plantations. This crisis has impacted both large estates and smallholders, with the latter being particularly vulnerable as they heavily rely on rubber cultivation for their livelihoods.

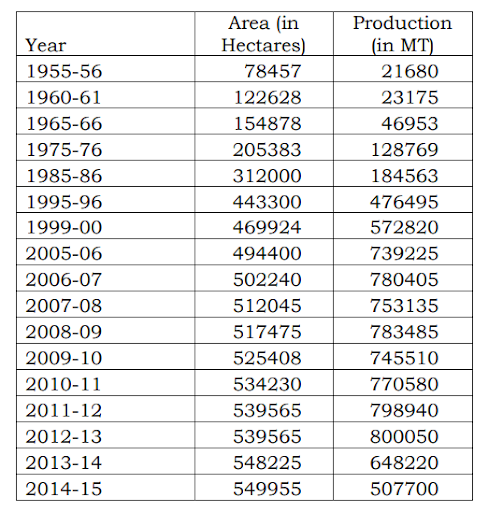

Kerala dominates rubber production in India, contributing significantly to the country’s output. Although there have been price fluctuations, occasional production shortfalls, and rising maintenance costs, Kerala has seen significant growth in rubber cultivation and production, with specific areas showing an increase in cultivation. The reasons for this expansion are unclear. However, the state’s share in the national rubber market has declined due to increased cultivation in other states. Many current planters in Kerala are holding off on tapping their trees in anticipation of better prices in the future. Despite challenges, the rubber plantation sector in Kerala remains strong compared to other crops in the state.

Today, many small and medium rubber growers in traditional regions like Kerala are losing interest in rubber cultivation and shifting to other crops or finding alternative uses for their land. The international market has caused wide fluctuations in natural rubber prices, leading to a recorded growth price of -33.455% in natural rubber from 2010-11 to 2014-15. The market price in 2024 is less than 50% of what it was a few years ago, resulting in severe hardship for small cultivators. The increasing production costs (tapping costs, chemical expenses, labour costs, and land development costs) have further exacerbated the situation for rubber cultivators, forcing them to live in poor conditions. Some have even abandoned rubber cultivation.

The key factor contributing to the declining price of natural rubber is the government’s import policy, and stakeholders in the industry have been demanding urgent policy reviews to reduce imports and improve domestic prices. The crisis has persisted for several years, prompting appeals and strikes for government intervention to save the farmers’ livelihoods. Immediate intervention is essential to prevent further decline in rubber prices and protect the livelihoods of cultivators.