Non-Brahmin Landlords in the Midlands

Land and Caste, Part 2

Syrian Christians in Kerala

The Syrian Christian community is dated to 52 A.D. when St. Thomas reached the Malabar shores and converted upper-caste families to Christianity. In the fourth century A.D., another group of Christians immigrated to Kodungalloor, Kerala. All the groups adopted the immigrants’ religious practices, including the Syriac language of worship. Hence, the native Christians came to be known as Syrian Christians.

The Vayattattils of Purapuzha

The Vyattattil family, a mid-level landlord of Purapuzha, Kerala, came here from Ernakulam. However, their migration to this village was because of their ancestral skills in Nattuvidayam (indigenous medical practice) allowing them to cure a member of the edaprabhu’s (chieftain) family. And in return, they were given a house and land close to the Kaimal chieftain’s tharavad to settle in. Even today, the descendants of the families stay close to each other at Purapuzha.

“Thailadhi vasthukkal ashudhmaayal, Nasraani thottal athu shudhamaakum.” [Liquids that have become impure will become pure when a Nasrani (Syrian Christian) touches them.]

– M.D. Kaimal, Nair Service Society, Purapuzha, 2024

Syrian Christians were accorded an important position in the southern princely states of Travancore and Cochin until the 19th century. Their skills were as crucial to the rulers as those of the Nair elite warriors because of their martial skills, their intermediary position in the caste system, and their role as traders and revenue officers. Arranged intermarriages between the Nairs and Syrian Christians were common until the late 16th century.

Land Surveys

The alliance of Travancore with the British forced the kingdom to maintain a military force, the cost of which had to be borne by the Travancore government. To raise this money, in the 18th century, it initiated land surveys to assess individual land holdings and fixed the tax based on this. Additionally, new wastelands were cultivated to generate revenue.

“In the 18th or 19th century, when the land survey happened for the first time in Travancore, surveyors came to Purapuzha and stayed at a house that belonged to my ancestor. This ancestor influenced the British officer and took possession of 400 acres of the surrounding land. This entire area belonged to us—around 400 acres. Before that, we did have some land. It was after the survey that the family came into possession of the bulk of the land in this village.”

– Babu John, retired headmaster, Purapuzha, 2024

The Edaprabhu family

The Kaimals, members of the Madurai Raja’s family, dispersed from Madurai after the Tirumala Nayakan attack of the 17th century. Travelling with the family diety of Madurai Meenakshy, they reached Neriyamangalam and settled down near the river.

Earlier, the pujas were done under some trees . Later, the tharas were removed, and temples were built in their stead. The branch in Purapuzha is called Mazhuvanchery Kaimal. At present, the Kaimal family members go to the family deity at least once a year to do pujas.

The temple is central to the livelihoods of various castes, including the Kaimals. Recognised as income-generating enterprises, owning a temple is more than a matter of pride. The Kaimals, in charge of governing the temples under their control, were a powerful community with access to local kings.

“Though the temples are now under the government and Devaswom board, whichever family is the sthani of the temple will have a prominent place in the daily rituals and other decisions.”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

“The Kaimal family probably had a say in the maintenance of law and order in the area. If there was a murder or other dispute, they were the judges.”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

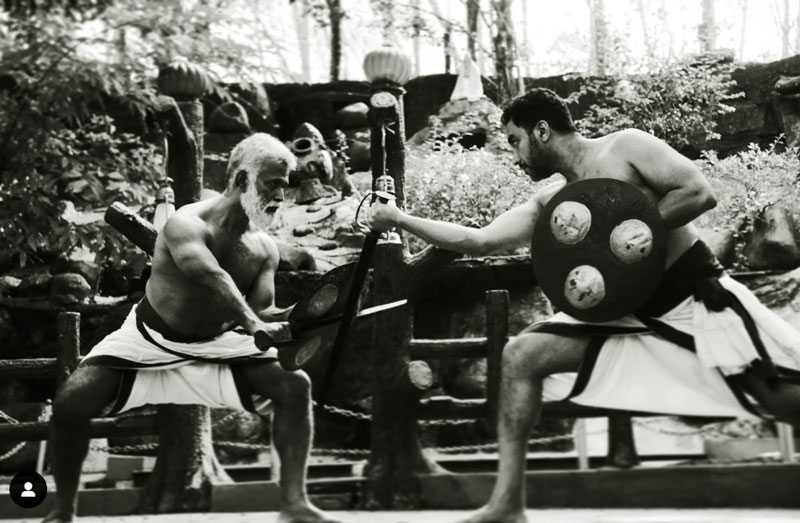

Being tax collectors, Kaimal family members trained in Kalari and were able to handle weapons. However, it was the Kartha community that were the warriors. The Meenachil Kartha family, originally from Madurai, were in charge of the local raja’s army. The kingdom was annexed to Travancore during the reign of Marthanda Varma.

Land and Cultivation

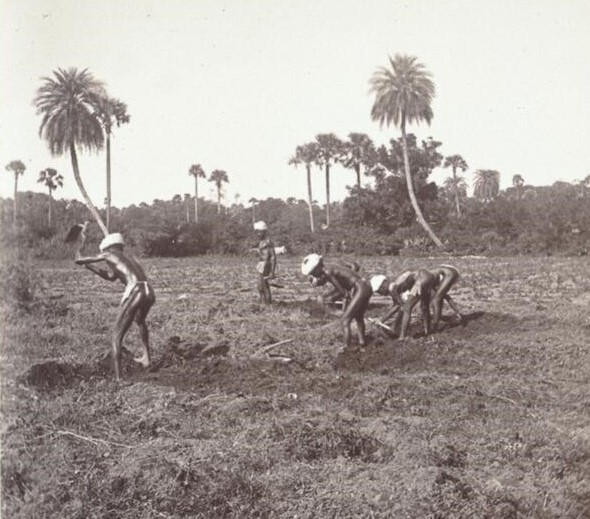

A significant source of income for these mid-level landlords, other than temples, was produce from the garden lands and paddy fields. Pepper is grown in between the coconut palms and areca nuts. Crops like tapioca, yams, and colocasia were cultivated for home consumption.

“The major cultivation on our land was paddy along with arecanut. Merchants would measure the nuts in rathal (local measure); it would be cut, dried, and exported. In the early 1940s, my father left the village to start cinema production. He asked for his portion of the money from the sale of pepper and areca nuts. Imagine the amount of produce they would have had for him to ask for this!”

– Babu John, Purapuzha, 2024

The Vayattattil family, though a landlord family, seems to have moved with the times. They began growing rubber in the 1940s on uncultivated land seeing relatives in neighbouring areas.

“After my father’s interest in film production waned, he started one of the first rubber industries in Kerala. It was called Vaijo Industries, later known as New Bharat Industries. This was before Indian Independence. We would procure rubber from Kanjirapally and Pala, and it was brought in trailers. The factory was in Nagambadam. It used to export shoe soles to London.”

– Babu John, Purapuzha, 2024

Water for Agriculture

Purapuzha is situated in the midlands of Kerala, and the paddy fields are all near water bodies. Farmers have access to water throughout the year. Hence, irrigation does not require much power consumption, unlike other agricultural lands.

There are varalli (small canal systems) that divert water from bigger canals. On fields on higher land, water was raised using mechanical and later electric equipment. Teak planks are used to dam the water and divert it to the varalli. Palm tree wood was used to line the sides of the canal in the past.

The Caste of Water

Even in the 1970s, lower castes were not allowed to directly draw water from the well belonging to the landlord families—however, all these changed by the early 1980s.

In the 1983 drought at Purapuzha, all the wells and streams around the original homestead dried up, except the main well near the tharavad. The well was opened to the entire village, irrespective of caste. People were queuing up day and night to bathe and wash. The Vayattattil family dug another well in their field to meet the water demand.

Ownership and Sharing

The Kaimals used to behave like landlords—they would take a bath and go to the temple in the morning. They had managers, mostly Nairs, to oversee the land.

“Our land was farmed by Nairs; in neighbouring areas, it was done by Christians. Normally, people from the lower class or caste took care of cattle and the cowshed.”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

“Some families did partnership (pankinnu) farming, and members of the same family would work as labourers. The farmer would get one part of the harvest, and we would get two-thirds of the harvest. Later, it became 50:50. We had to provide the seed and fertilisers. Rice kept aside from the harvest was given as seed. There was a section of the ara that was specially built for seed storage.”

– Babu John, Purapuzha, 2024

Compensation or Wage

“The agricultural workers were given paddy instead of money. Payment in cash came later. The workers were paid once a week. The palla (stem) and coconut, or palm, leaves are spread out on the ground. The paddy was measured and poured onto it using local measures. A quantity of tubers were also given.

During festivals, all the tenants gifted coconuts, plantains, banana bunches, and sometimes rice, to the house of the landlord. It was called kazhchavakkukka. In return, they were given clothes—mundum neriyathum (two-piece body wrap) and thorthu (cotton bath towel).”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

“Tools and implements like knives, spades, carving knives, axes, cheenachatty (wok), and earthenware for the household were bought during festivals from people who made them. Curries were made in currychatty made of mud or kalchatty made of stone.

A few Jacobites (non-Catholic Syrian Christians) from Puthenkurish would bring woven utensils needed for paddy cultivation—mats, baskets, and so on. They would be provided food, and alloted space on the landowner’s veranda for the night. The traders exchanged goods with the householders and moved on to trade with other families in the village. They received paddy as payment; later, it became cash.”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

Caste and Work

The outlier or lowest castes would not have been allowed to enter the landlords’ compounds, though they would work in their agricultural fields. Unlike Namboothiri homes, the Kaimal women depended on Nair women as housemaids and nannies.

Nevertheless, in Kaimal and Syrian Catholic households, other castes were not allowed in the kitchen. At Vayattattil tharavad, the Ezhava women helped with the grinding, sorting, and so on. However, it was only in the 1960s that they were allowed to help with the actual cooking.

Family Rites

In the past at Purapuzha, when inter-dining was not common, the Nair tenants would partake in the snacks served at their Syrian Catholic landlords’ homes, but would not stay for the meal.

For chaatham (annual death rite), the lowest castes, called puravar, would come en masse to the feast arranged by landlords. A shallow depression would be dug and lined with leaves. The entire feast would be served in this, one for each family. These feasts were open not just to the Pulaya and Paraya – the puravar – but also to the homeless and beggars. These families would carry home whatever was left of the food served to them.

Moving Away

Since Purapuzha is primarily an agricultural village, there are not many jobs available for the educated youth. Moreover, the land reform laws took away large tracts of cultivable land from these landlords and converted them into small holdings.

“A 100-year-old aadharam, title deed, belonging to the family describes how 250 acres of land were divided into 28 plots. Now, many of them have migrated and only 4–5 families remain in the village. Additionally, the land was not cared for properly, and other villagers encroached onto the land. Currently, there are no wealthy landlords in the family. Everyone just about manages to make a living.”

– M.D. Kaimal, Purapuzha, 2024

Land reforms, matrilineal laws, division of ancestral property, and modern education ended the jati-janmi-naduvazhi (caste-landlord-chieftain) system to a great extent in Kerala. Mid-level landlords, who held considerable land, were affected by the abolition of their statutory landlord status. The younger generation is not interested in agriculture, which was the main source of income in the past. The high labour charges have made the cultivation of labour-intensive crops like paddy untenable, and many fields lie fallow in Purapuzha. Now, most of the labourers are migrant workers and only a small number of the lowcaste landless village labourers remain.

Subdivision and fragmentation of land holdings waste time and labour in moving seeds, manure, and implements across plots. Moreover, irrigation becomes challenging in fragmented fields. The lack of decentralised storage and processing facilities further complicates matters and makes farming an increasingly unremunerative activity.

Many thanks to M.D Kaimal and Babu John for contributing to this article.

Exhibition Research & Content : Janal Team, Kerala Museum 2024

This exhibition is based on the Janal Article. “Land and Caste, Part 2: Non-Brahmanical Landlords in the Midlands”. JANAL Archives, 2024.

References

Aiya, V. Nagam. The Travancore State Manual. Vol. III. Trivandrum: Travancore Government Press, 1906.

Bayly, Susan. “Hindu Kingship and the Origin of Community: Religion, State and Society in Kerala, 1750-1850.” Modern Asian Studies 18, no. 2 (1984): 177–213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/312432.

Malekandathil, Pius. ‘Dynamics of Trade, Faith and the Politics of Cultural Enterprise in Early Modern Kerala’. In Clio and Her Descendants: Essays in Honour of Kesavan Veluthat, 157–98. New Delhi: Primus Books, 2018.

Pillai, T.K. Velu. The Travancore State Manual. Vol. II – IV. Trivandrum: The Government of Travancore, 1940.

Varier, M.R. Raghava. Madhyakalakeralam: Swaroopaneethiyute Charithrapatangal. Kottayam: Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society Ltd, 2014.