“The main reason we are forced to make a livelihood from collecting kakka (clams) is because there aren’t enough fish left to catch in the Vembanad Lake. The few fish just meet our daily needs, but it is not enough to sustain a living by fishing.”

- Fisherman Ratheesh, Village Muhamma, 2023

The Vembanad Lake is a large shallow lake, the second largest Ramsar wetland site in India after the Sundarbans. The ten rivers, of which four flows into the Thanneermukkom region, bring a lot of silt, and this has made the lake quite shallow, with a depth of 3 to 4 metres.

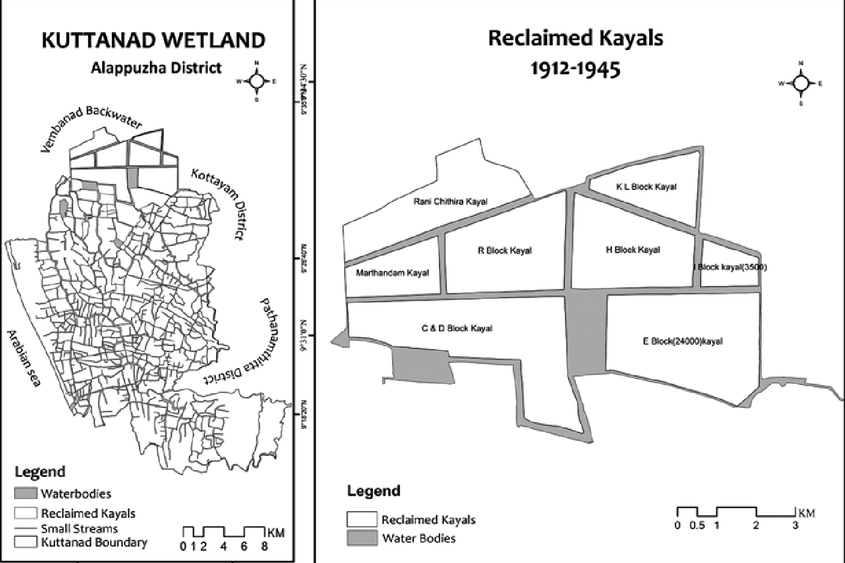

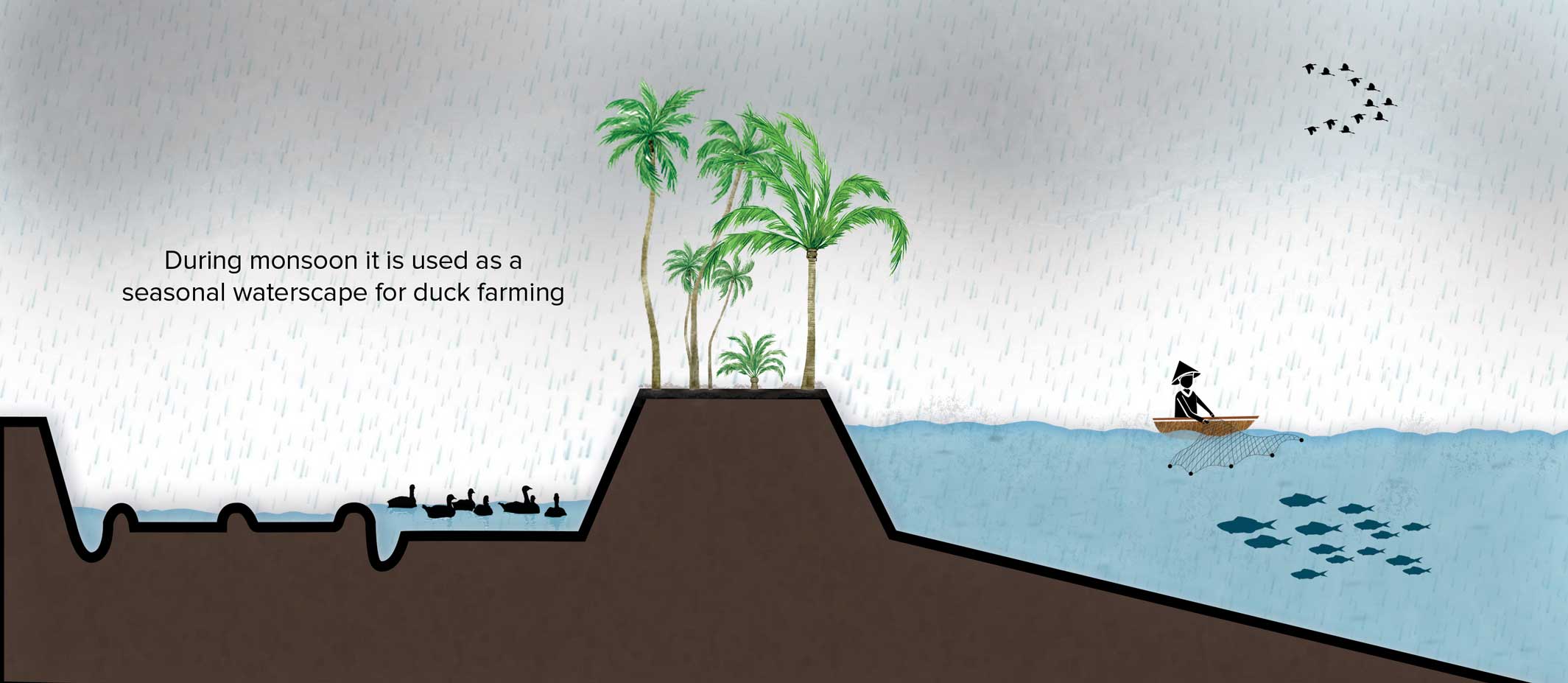

In earlier times, reclamation was carried out mainly from the shallow part of the Vembanad Lake or from the periphery of the Pamba River, by the deposit of river borne sediments. These reclamations formed small paddy growing areas. Around 150 years ago, artificial land reclamation (kayal nilam) for paddy cultivation began in the southern part of Vembanad lake. During the annual monsoon, fresh rain water overpowers the tidal saltwater flows, making the reclaimed kayal ideal for cultivating a crop of paddy a year.

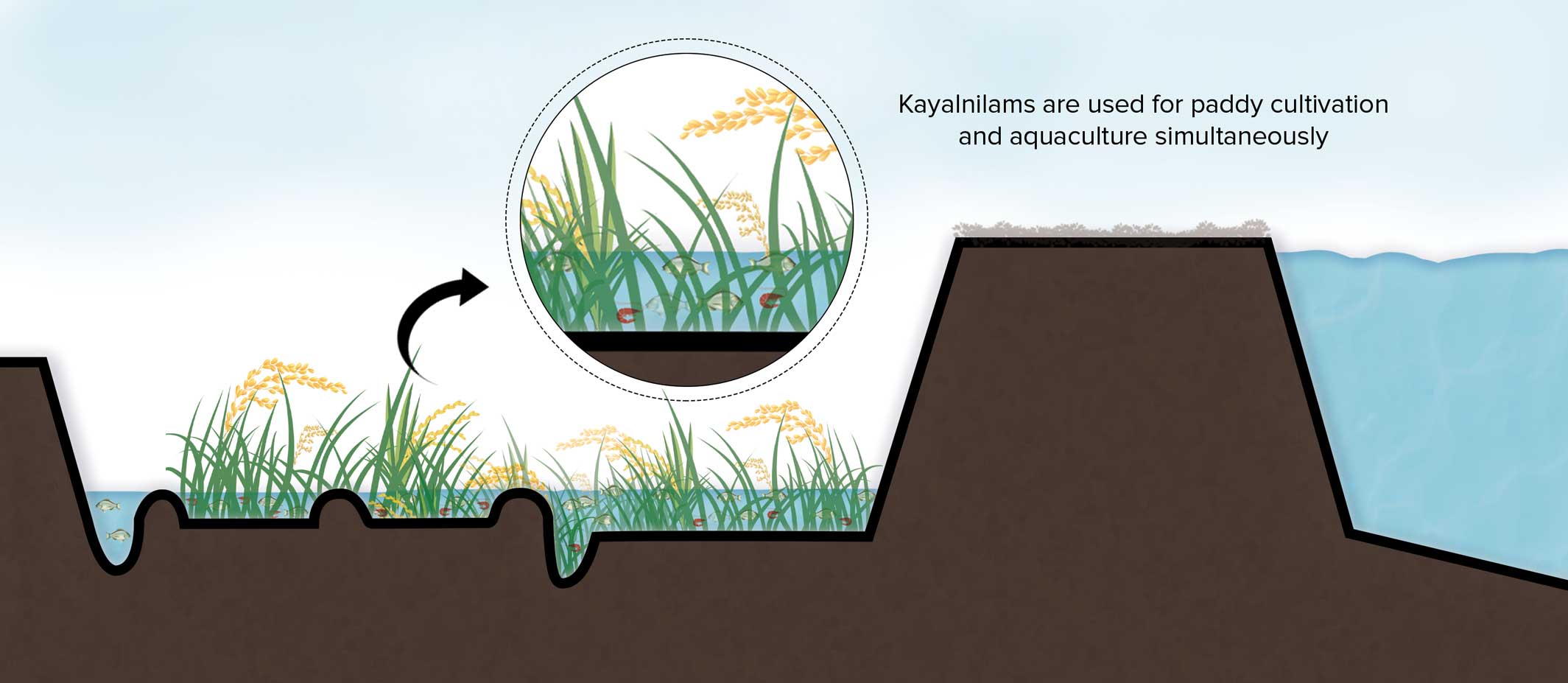

Fisherfolk have been living off the lake for centuries, with a catch including fish species like Karimeen (Pearl spot fish) that migrate between the freshwater and saltwater ends of this coastal wetland. Rotating between agriculture and aquaculture, the people of Vembanad have lived in harmony with the seasonal mixing of fresh and saline water.

However, to improve the farming capacity of the Kayals, it was necessary to keep the saltwater away from them for a longer time. The construction of the Thannermukkom barrage made in stages from 1976, divided the lake into a freshwater-dominant southern zone and a saltwater-dominant northern zone. The cultivation of two or more harvests in a year is at the cost of obstructed fish movement, affecting fisheries and marine life.

The process of backwater reclamation in the Kuttanad wetland is called Kayal Kuthu. The earliest bunds called padashekaram, to hold the silt and soil, were formed naturally during the dry season, as much sediment is deposited here by the four rivers discharging into the Thanneermukkom region.

Today, some estimate that as much as two-thirds of the lake and its marshes have been reclaimed for growing rice, each mega-paddy field named after the local king who approved the British plan for its creation. From above, the kayalnilam look like angular pieces of land intersected by water, all straight lines and sharp corners. This rearrangement of the natural landscape has drastically altered the ecosystem, in ways often unpredictable for marine life of lake Vembanad.

View from the shore: Thanneermukkom Bund

A timeline of the Vembanad Kayal Kuthu (Backwater reclamation)

Below Sea Level Land Reclamation by Bunding

Kuttanad, a low-lying wetland is the only place in the country where paddy farming has been practised below sea level for more than two centuries. In this system, the artificially created landforms are called kayalnilams, where kayal means backwaters and nilam means ground, implying that they were lifted out of water.

Today, some estimate that as much as two-thirds of the lake and its marshes have been reclaimed for growing rice, each mega-paddy field named after the local king who approved the British plan for its creation. From above, the kayalnilam look like angular pieces of land intersected by water, all straight lines and sharp corners. This rearrangement of the natural landscape has drastically altered the ecosystem, in ways often unpredictable for marine life of lake Vembanad.

Drainage for reclaimed land maintained by regular repair of Kayalnilam bunds.

The kayalnilam system of earthen dykes, canals, and ponds that rise and fall above the backwaters accommodates seasonal flooding and salinity intrusion, allowing the residents to grow rice, coconut, and other fruit trees through the local technology and water management practices associated with the kayalnilams.

Keeping Paddy away from Seawater

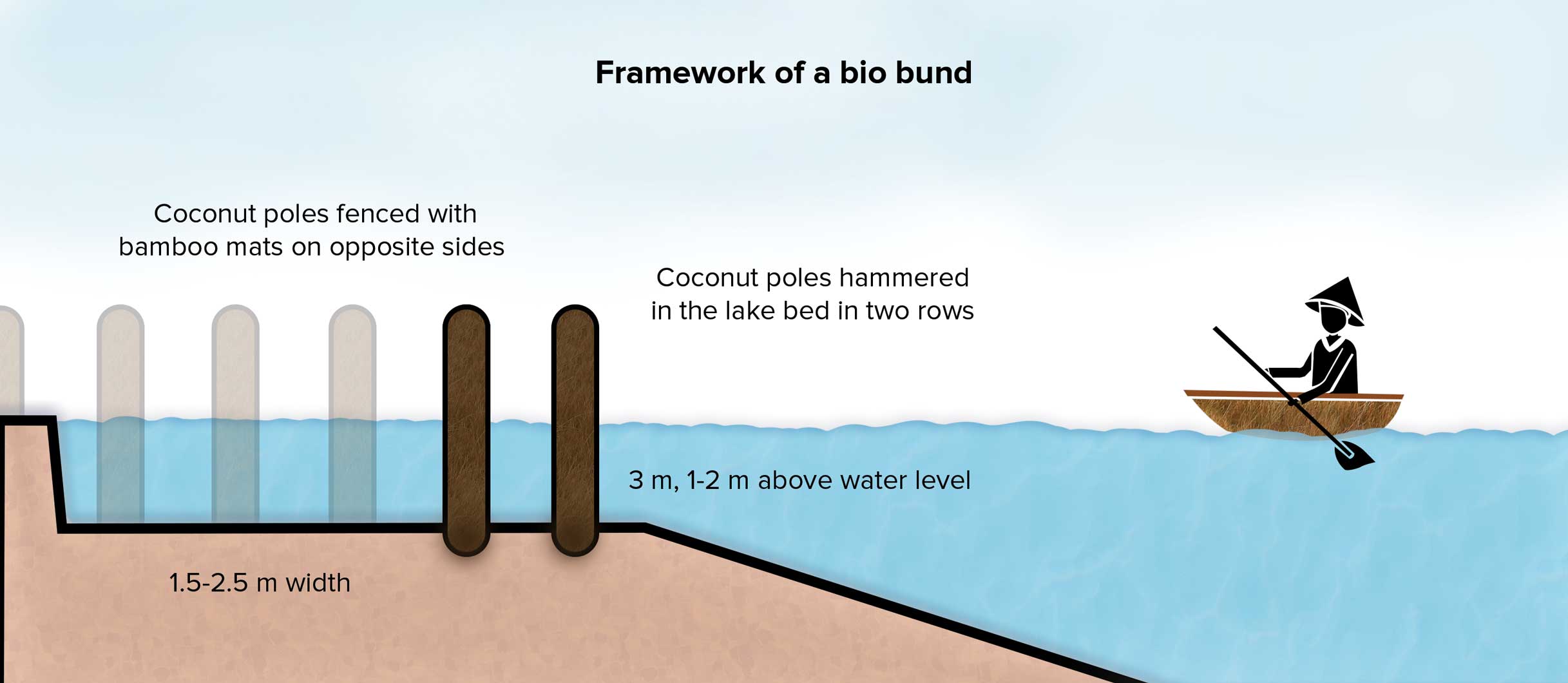

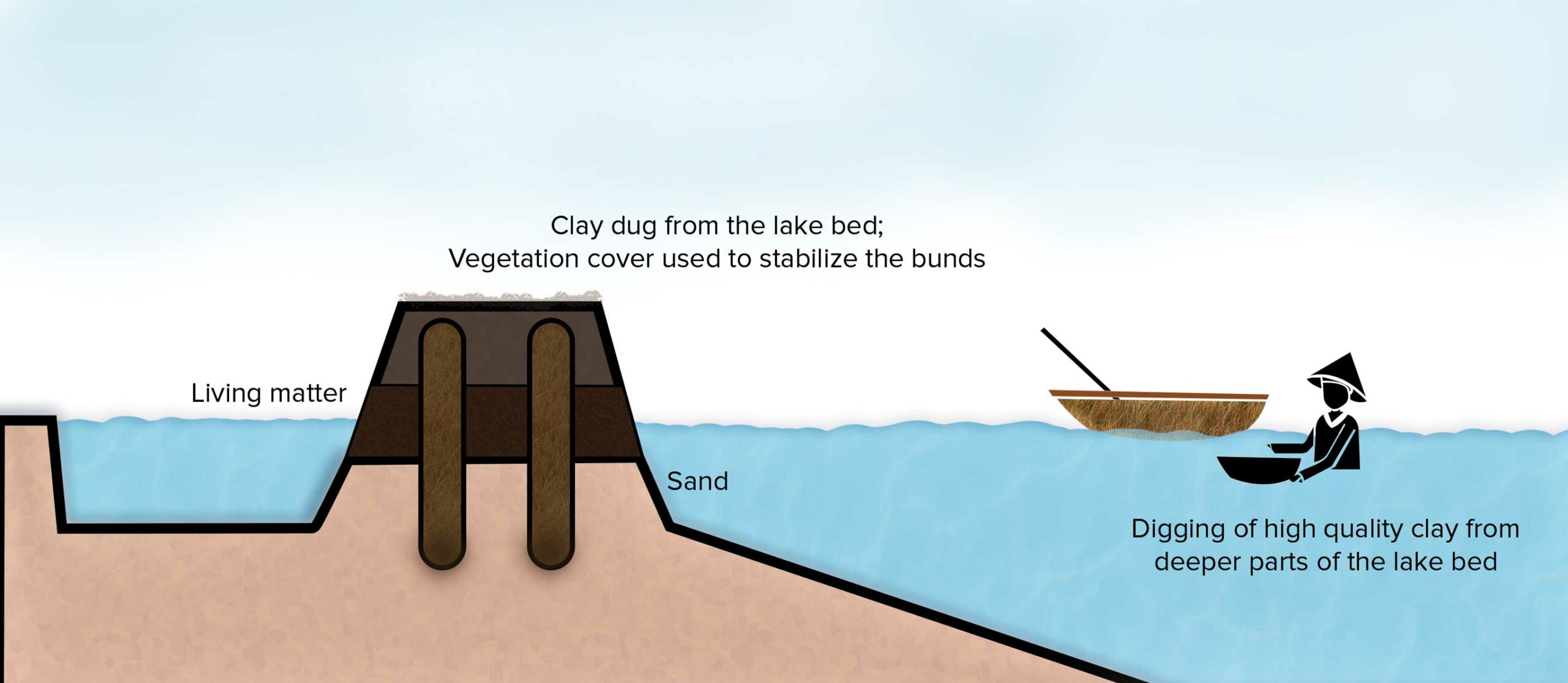

A framework for the bio bund is erected using coconut poles fenced with bamboo mats along the periphery of the shallow parts of the lake bed. The channels of the bund are filled with high-quality clay dredged from deeper parts of the lake, along with sand and organic material like twigs and certain plants. Vegetation cover is used to stabilise the bund. The bunds separate the canals which hold water used for irrigation.

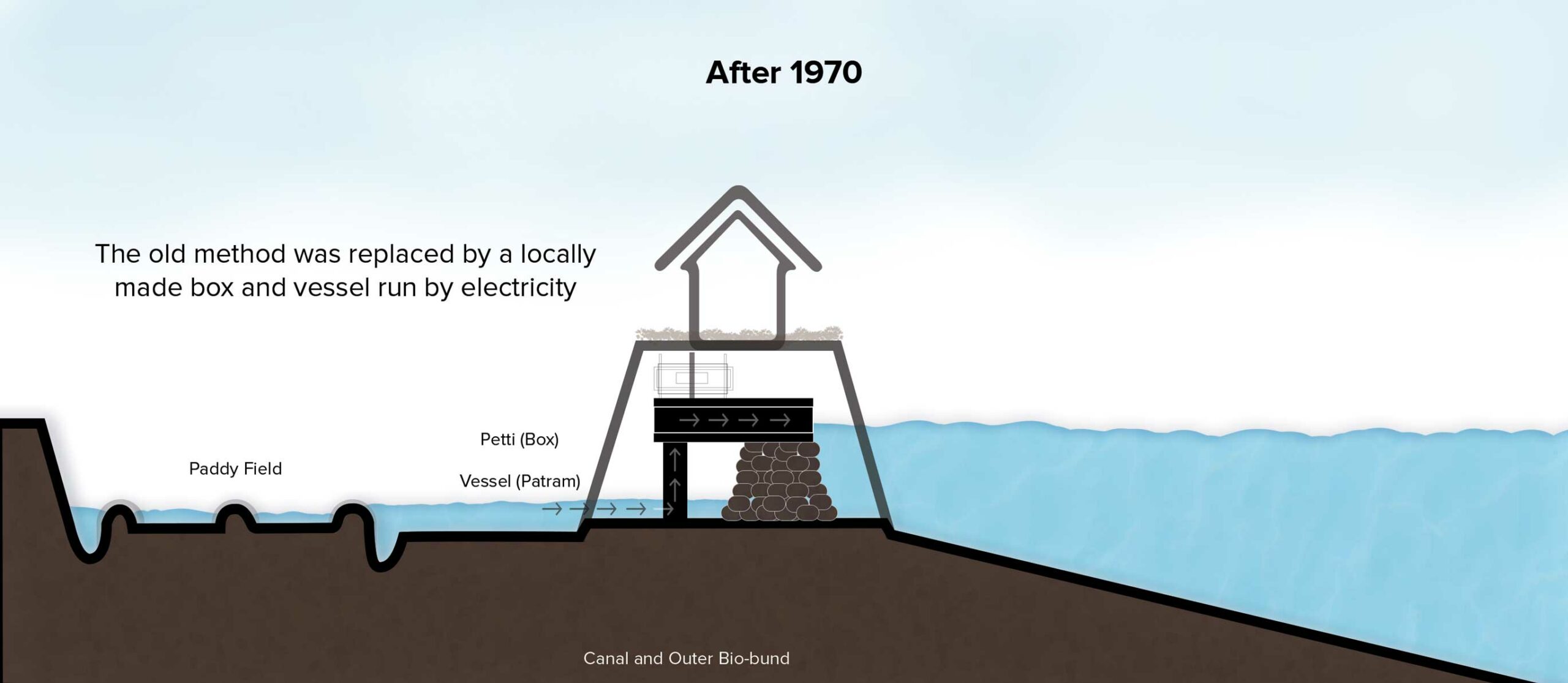

The water enters the paddy fields through a flexible opening in the bund called a thoomba. However, to avoid excess water entering the paddy fields, dewatering technologies called pettiyum parayum are placed at strategic junctures between the bunds and the canals.

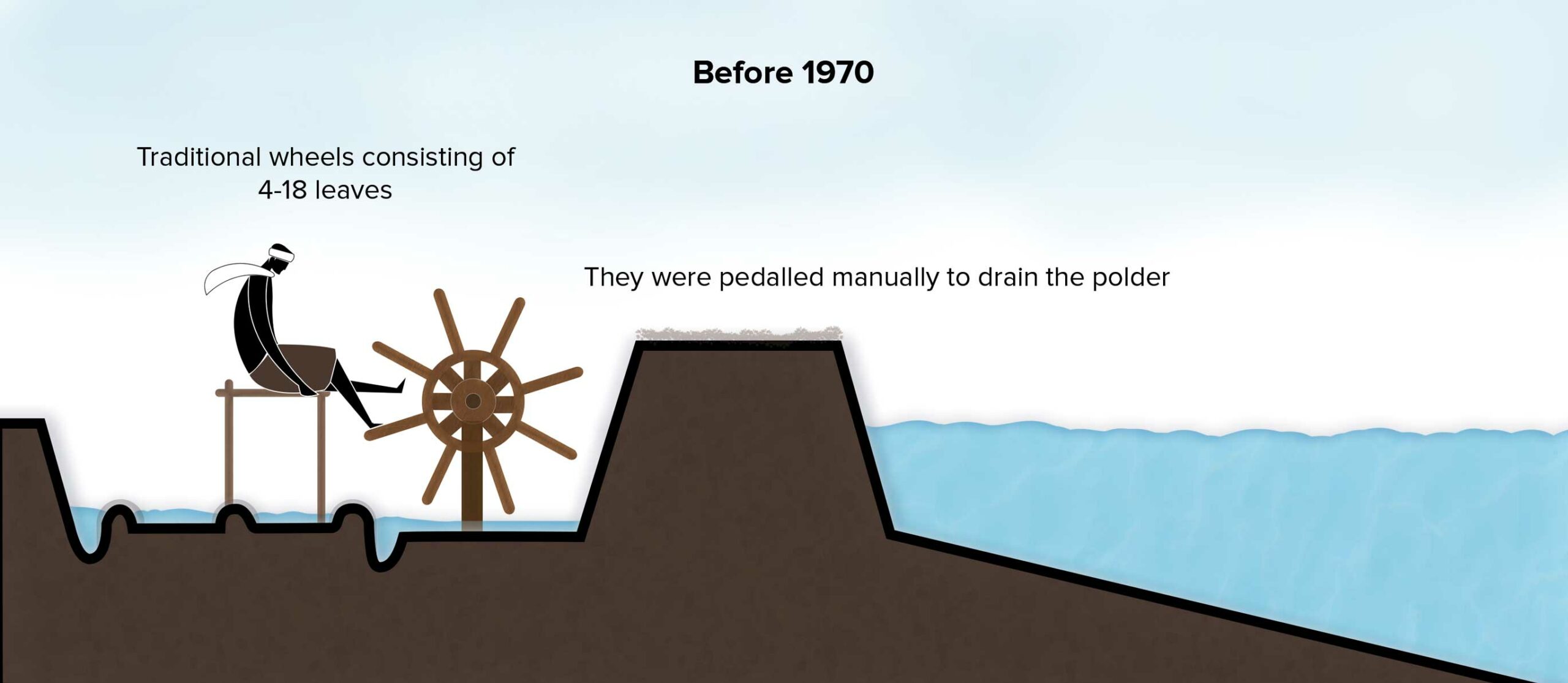

Before 1970, wooden water wheels from four to eighteen leaves were pedalled manually to drain the water from the reclaimed land. Since then, they have been replaced by locally crafted ingenious machines that run on electric power.

To block the seasonal entry of salt, temporary barriers called orumuttu, made of sandbags and twigs are built above the saltwater level, allowing only fresh water to enter the paddy fields. The entire system is lined with an exterior bund which acts as a sea defence barrier against fluctuating tidal levels.

Glimpses of a Harvest

A study in the 1980s said the lake had 180 species of fish. Since fish count began in 2008, the maximum number of species we've found is 117." - Jojo, ATREE in Alappuzha, 2023.

What is happening to Karimeen in Vembanad?

Acclaimed as the ‘inland fish basket’ of Kerala for centuries, the southern stretches of Vembanad were contributing forty to fifty percent of the total catch before the construction of the barrage. By 2001, the southern stretches of the lake provided a mere seven percent of the total catch for the entire Vembanad lake.

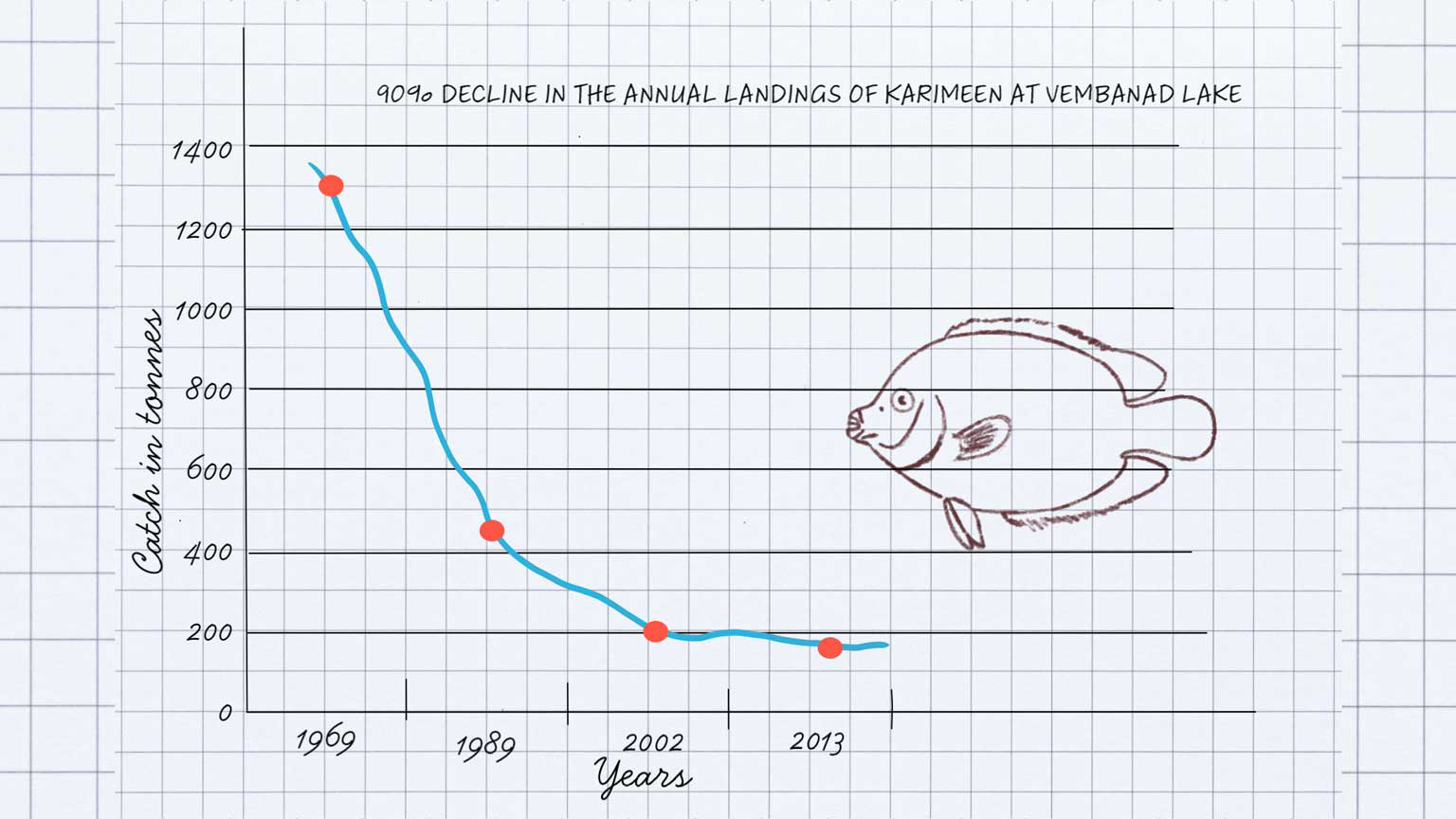

Since the operation of the Thanneermukkom Barrage, the annual landings of Karimeen, the State Fish of Kerala, from Vembanad Lake has gone down 90% from 1969 to 2013. Local fishermen also note that the average size of Karimeen in their catch has reduced substantially in the last five decades.

Three easy steps to kill a lake?

The Thanneermukkom Barrage was designed to keep half the lake filled with freshwater long enough to allow for one rice harvest.

However, the pressure to increase paddy production by growing two rice harvests on the reclaimed land has restricted the time that brackish seawater can cross the Thanneermukkom barrage barrier.

This has three main impacts on aquatic life on the lake.

Hyacinth - the invasive foreigner

The fishes in backwaters require a small amount of saline water for their breeding. Fish breeding is affected by the presence of the bund, which restricts the movement of fish and saltwater.

Earlier, the saltwater tended to cleanse the backwaters, but this does not happen anymore. This restriction has interfered with the natural cycle and enabled aquatic weeds like water hyacinths to spread at an alarming rate.

Many thousands of tonnes of fertilisers and highly toxic pesticides are used in the paddy fields. A considerable portion of this enters the water bodies when the water drains from the fields. Tissue samples of fish, shrimp, and clams from Vembanad Lake contain pesticides that were as much as ten times the acceptable toxic levels for the respective species. Some of these chemicals are well-known carcinogens.

The only way to revive this system is to let the salinity come as it used to, by keeping the gates open longer. Keep it natural, that’s it.

- Jojo, ATREE Co-ordinator, Alappuzha