Chaldean and Syrian Christians

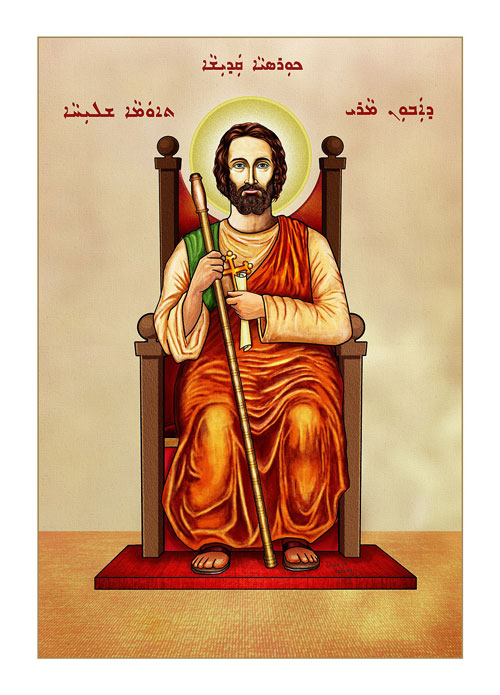

It is believed that Christianity reached South India through Kerala in the first centuries of its origin and development. The earliest Christians were referred to as Syrian Christians due to their connection to Eastern Christianity, with Syriac/Aramaic as their liturgical language. Of the Syrian Christians, the Chaldean Christians, also known as Nestorians, are one of the oldest sects. While the term ‘Chaldean’ is used in the Middle East to refer to the Christians affiliated with Rome, in the Indian context, it refers to the Nestorian group in Kerala.

Along with the legend of the Apostle Thomas, an alternative view exists that Christianity was introduced to the Malabar coast by East Syrian traders in the first century. Both legends confirm the existence of a Christian church with an East Syrian connection on the southwest coast of Malabar in the first few centuries of the common era.

When the Portuguese arrived in Kappad in 1498, the Church in Malabar was Syrian and was visited by bishops from Persia. There is evidence that East Syrian liturgy was used in Kerala in the early days of Christianity, and the Syrian Church in Kerala was undivided until the advent of the Portuguese.

Portuguese Interference

The Portuguese missionaries tried to take control of the Syrian Christian communities and change their religious practices and liturgical language from Syriac to Latin. They stopped all the Syrian bishops coming from the Middle East and placed the Syrian Christians under a Latin-Portuguese bishop. During this tumultuous period, in 1552, the contemporary bishop of the Nestorians in Kerala, Mar Yakob, died.

Mar Abraham, Yakob’s successor, was able to control the Syrian Diocese only nominally. In 1597, Mar Abraham died, leaving the administration in the hands of Archdeacon George. This was when Alexis De Menezes, the Archbishop of Goa, called the Synod of Diamper, a significant event in Indian Christian history.

Synod of Diamper

The Synod of Diamper was held on 20 June 1599 in Udayamperoor. It aimed to eliminate the Nestorian influence in the Indian Church. The Synod commanded Catholic priests and followers to deliver all the books written in Syriac to the Metropolitan so that they could be “perused and corrected or destroyed.” The Syrians and their leader, Archdeacon George, had to acquiesce to these decisions. Thus, most of the books that contained the history of the Syrian Church were destroyed as the Indian Church was incorporated as a part of the Western Church.

Rejecting the Latin Church

After the death of Archdeacon George in 1637, his nephew Thomas assumed leadership and a spirit of resistance seized the Syrians. Thousands of Syrian Christians gathered at Mattancherry in 1653 on the arrival of the bishop, Ahatalla, of the Eastern Church. But the Portuguese sent him off to Goa, and news spread of the death of the bishop by drowning at sea.

An angry crowd assembled near the Portuguese fort revolted, swearing not to obey the dictates of the Archbishop of Goa and the Latin hierarchy. Holding on to ropes tied to a huge granite cross there, they took an oath known as the Coonan Cross Oath, a protest against Latinisation and a defiant plea for the Syriac rite.

Schisms From Within

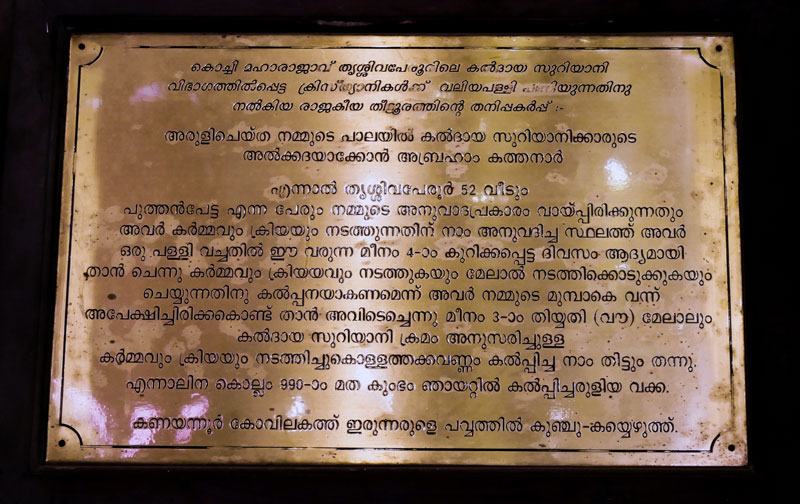

After the Coonen Cross Oath, the Syrian community split into two sects, Pazhayakuttukar (under Rome) and Puthenkoor (under various bishops). The Syrian Christian churches underwent further schisms over the centuries. Meanwhile, the Chaldeans strived to hold on to their East Syrian roots and consolidate themselves as a separate faction affiliated with the Church of the East. This led to the settlement of 52 Chaldean families in Thrissur in 1796 and the establishment of the Marth Mariam Chaldean Church.

The Church and the Kingdom

After the attack by Tipu Sultan in the second half of the 18th century, Shakthan Thampuran of Cochin state decided to improve commerce by developing Trichur town and settling the Chaldeans there. In 1815, the church was consecrated by Archdeacon Abraham Palai following the royal charter of the Maharaja, using the Chaldean Syrian rite.

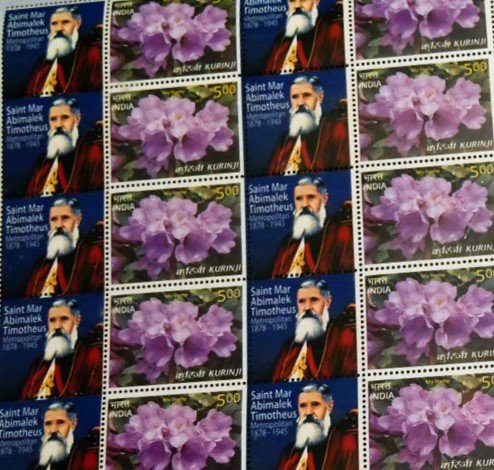

In subsequent years, the dispute of having a consecrated official leader persisted as many priests were either blocked from travelling to India or sent back to Persia under the orders of the Vatican. Thus, the Chaldean community could not exist as a separate congregation until Mar Abimalek Timotheus intervened.

An Independent Chaldean Church

In 1911, Mar Abimalek Timotheus’ predecessor, Cor-episcopa Michael Augustine, issued a legal suit against him which claimed that he must conform to the current customs of the now ‘Independent Chaldean’ community and not change anything. This situation forced Mar Abimalek Timotheus to conduct mass outside the Cathedral until he won the case in 1925 and consolidated the community as an independent congregation.

Local Connections

The church, established with the cooperation of the Maharaja of Cochin and other Hindu overlords in the region, incorporated secular / collaborative practices with nearby Hindu temples. For instance, the church donates oil to the Parmekavu Temple during Thrissur Pooram. In exchange, the temple donates an ornamental umbrella traditionally used in temples in Kerala for the annual church festival.

Administration of the Church

The Patriarch heads the global community assisted by the Metropolitan and intermediary leaders, including the Archdeacon and Episcopa. In the past, the religious heads were elected from Syria. This changed during the second half of the 20th century when Malayalis were also chosen as the heads of the congregation.

Chaldean Syrian Christians follow a democratic mode of administration, where the council members of the diocese, barring the religious leaders, are elected by the church’s followers. The Marth Mariam Chaldean Church was established as the Indian base of the Church of the East, while connected to Kerala’s religious institutions and local practices.

The vicars under this church are allowed to marry and lead a domestic life, while the top religious leaders have to practice celibacy.

The Church of the East based in Thrissur has 30,000 members out of India’s estimated 75 lakh Syrian Christians (or St. Thomas Christians/Nasranis). The followers of the Church are spread around India in major cities like Chennai, Mumbai, and Bengaluru. The Marth Mariam Valia Palli is the sole base for the Indian section of the Chaldeans, represents the endurance of a two-millenia-old community that maintains its unique identity while adapting to the local traditions of Kerala.