“For us, the company (the tile factory as it is known locally) is a very important part of our lives, identity, and livelihood. It is one of the things that Feroke is known for.” - Sreekumar, Executive Director, Tile factory, Feroke, 2024

For the last 160 years, the Commonwealth Tile Factory, locally known as the oodu or tile company and now a historical landmark, has played a central role in the lives and livelihoods of the region. It had an instrumental role in influencing the architecture of the region, replacing thatched buildings with tiled roofs. In the process it brought considerable changes in the lives of people of the region, modernising their lifestyle.

Feroke: Cradle of the Tile Industry in Kerala

Feroke, located on the southern shore of the Chaliyar River in Kozhikode, has long been a key hub for trade and commerce. Initially part of the Parappanad kingdom, it became part of the Mysore Kingdom in the late 18th century. Tipu Sultan sought to make it his headquarters in Malabar, naming it Farooqabad. After the Third Anglo-Mysore War, it came under British control and was renamed Feroke. Its strategic location near the Chaliyar River and Beypore port and the British development of railways solidified its importance in trade.

"We continue to honor our legacy by using the original German machinery and maintaining the classic German-style 'choolas' (kilns), preserving the art of tile-making as it was perfected generations ago."-Aboobacker, tile factory worker, 2024.

The Missionary Tile Factory

The Basel Evangelical Mission (BEM), founded in 1815, aimed to promote global humanitarian development. They initially moved to the area of modern Karnataka and came to Calicut in 1842. Unlike Cochin and Travancore, Malabar was less influenced by other missionary societies, and the BEM view of 'work as worship' used factories to instil a Protestant work ethic and discipline, while also serving as community-building spaces. At this time, occupations were hereditary, and limited by caste, and backward castes like the Thiyya and Billava were excluded from many livelihoods. Those who converted to Christianity faced social ostracization, but they formed the majority of the converts. The BEM formed a commission to explore the industrial sector and set up weaving units and tile factories.

In 1864, missionary George Plebst, trained in clay treatment in Germany, established a tile factory in Mangalore, marking the start of large-scale clay tile production in Kerala. Seven more factories were later established near ports and railways as demand for clay tiles grew, replacing thatched roofs for their safety and low maintenance.With declining profits from weaving due to British competition, the mission shifted its focus to tile production. A factory was set up in Feroke, chosen for its quality clay, water supply, and transport links. The Feroke Bridge further improved connectivity, boosting production to meet increasing demand from railway projects and the Public Works Department. The factory also served as a community hub, with workers’ children attending a BEM school nearby.

“This place has so many layers of history. Even after so many years, I can still learn something new and interesting about the factory’s past.”-Jijo Valsan, production officer, 2024

The Factory Through the Years

The tile factory in Feroke in 1905, was taken over by the British during World War I when Germany and Britain became adversaries. However, after the British takeover, the factory was run with a focus on commercial success, and working conditions became harsher. British officers monitored workers to suppress any labour unrest.Following India's independence, ownership was transferred to the Commonwealth Trust, which continues to operate it. The Trust paid annual royalties to the British until 1970. Despite various challenges, the factory has thrived, and it remains the only tile factory in Feroke, surviving, its unique tile-making process unchanged since 1905. Jijo and Sreekumar, writing the history of tile making in Feroke, note that most of the 10 to 20 tile companies here closed due to the scarcity of suitable soil and labour, leaving the Commonwealth Tile Factory as the last one standing.

“Yes, there are modern methods that are easier, but we believe that the quality of the tiles we make using this century-old method can never be achieved using those modern methods.” – Vinod, Tile factory worker, 2024

Tile Making

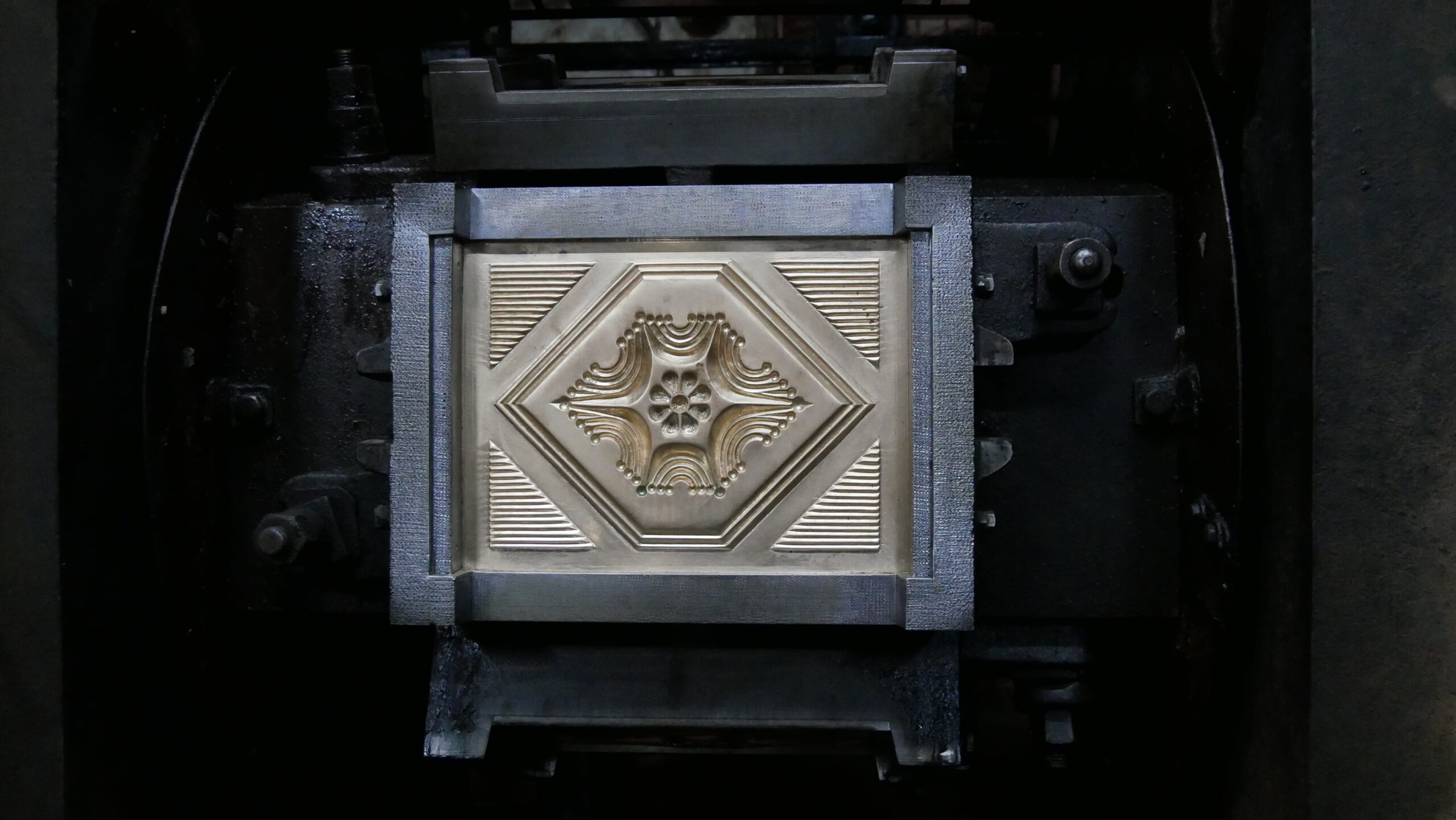

The process of making the tiles has multiple steps. Two grades of clay are used in the process of tile making. The first is lean clay, which has about 25% sand content and is coarser than the second, called plastic clay, which has only 6% sand content and is a better quality of clay. Both these are added in a 2:1 ratio and mixed in a pan mill. The resultant clay mix is ground in a High Speed roller to create a smooth consistency. Then it travels to another part of the rolling machine for de-airing. Here, all the air bubbles and pockets in the clay are removed before final mixing, after which the ready to fire clay comes out as slabs. The slabs are hand cut into required sizes, and a mixture of rice bran oil and kerosene is applied before being inserted into moulds for shaping. After this step, a worker cuts the excess clay from the edges and removes the tile from the mould.

Tile Baking

| The tile is then shifted to the drying area with long parallel shelves reminding one of a vast library. And in between shelves, there is a trolley-like system for moving the tiles to and fro. It is dried here for at least eight days before it is shifted to one of the 50 kilns on the ground floor. The kilns built with fire brick and surkhi mortar and connected to the chimney, is one of the most important parts of the factory. When the kiln is working, its stove is burnt around the clock using local firewood fed from the upper floor. The furnace is filled with dried tiles, which are fired in high heat to bake and ensures the strength and durability of the tile. After firing and cooling, the tiles are sorted and shifted to the loading bay from where they move out of the factory. |

A Legacy of Handcrafted Tiles

However, the factory now faces an uncertain future. The workforce has dwindled from over 650 to just 350 workers, primarily due to the scarcity of suitable soil for tile making. Rapid industrialisation depleted local soil resources, forcing the factory to import soil from Tamilnadu and Karnataka at high costs. Additionally, the factory's adherence to older production methods has led to financial losses, as it missed the benefits of modern, cheaper techniques. The decline in demand for tiles, driven by competition from Chinese tiles and the growing preference for concrete roofing, has further challenged the factory's viability.

The Feroke Tile factory has been pivotal in transforming Feroke from a small village into an important industrial hub, significantly impacting the local economy and community. As one of the first factories in Kozhikode, it provided thousands of jobs, offering workers a break from feudal slavery and introducing them to modern education, employment, and self-respect. The factory's fixed working hours along with food and rest breaks departed from the arbitrary labour practices in the existing feudal system. Over the years, Feroke Tiles gained a strong reputation, with customers trusting the production process, which has remained unchanged since 1905.

“We are the last people here, I cannot say if the next generation will be able to see the factory running.” - Vinod, a worker at the factory, 2024.