Whats New: JANAL Talks in June: Check our Events!!!

Whats New: JANAL Talks in June: Check our Events!!!  Whats New: JANAL Talks in June: Check our Events!!!

Whats New: JANAL Talks in June: Check our Events!!! June 2019

The year 1947 changed the course of history for every Indian. India, a new nation was born, freed from the clutches of decades of colonial domination. What was went unnoticed was the birth of a new nation; a dominion that a community scattered sporadically across the globe had prayed for, their fatherland: Israel. What followed was the largest migration the world would witness. Jews from different parts of the world left their homes to move to a land that they thought was lost to them; the land they hoped they would return back before their death; their home. This phenomenon resonated a blend of hope and uncertainty; of fulfilment and helplessness in the small hamlet of Chendamangalam where a community of Malabari Jews had settled for centuries. There were a conflicting feelings among the members: was it actually safe to go back to a land unfamiliar leaving all they have earned? In Aliya, his historical fiction novel, writer Sethu depicts the life of the Jew community in Chendamangalam and their migration to Israel. He is a prolific writer known for his remarkable novels like Pandava Puram, Aliyah and Marupiravi. He was honoured with Kendra Sahithya Academy Award in 1982 and 1978 for his works Pandava Puram and Pedi Swapanangal and Vayalar Award for Adyalangal in 2005. He also served as the chairman and CEO of the South Indian Bank. What encouraged him to write about this vibrant tale of a community who fought their way through the course of history just to survive and to live in peace, is rather interesting. A native of Chendamangalam himself, he recounts, “ I remember that there was a procession by them holding the national flag of Israel. People were in a hurry to return back to their fatherland. I was in awe how someone could leave everything that they ever had and migrate to a place they don’t even know. A place that has been latent in the map till now.”

The Chendamangalam Synagogue is the remaining vestige to the Jewish culture that had prospered. The Jews in Chendamangalam were the Black Jews (Sephardic Jews with Spanish origin). They were considered inferior by the Ashkenazi Jews or the White Jews and were restricted from entering Paradesi Synagogue in Mattancherry. “They had to go through too many formalities and red tape in order to migrate to Israel due to the lack of contacts. Adjusting to the topographical transition from lush, tropical Kerala to the arid and dry Israel was the most difficult barrier they had to go through post migration.”

When asked about the sources used to write the text, he disclosed the fact that he had gone through a lot of research and consulted historians like M.G.S Narayanan while writing both Marupiravi, (his other historical fiction novel about Chendamangalam), and Aliya. In Marupiravi, he states that the foreign traders badly wanted pepper to preserve meat during the winters. Pepper became the catalyst that motivated the traders to keep trade relations with Kerala. We get to know about this from the Sangam Paatukal and the Tenth Century inscription copper plate inscription (Tharissapali Inscription) given to Joseph Rabban by Bhaskara Varman. These sources provide obscure details about the society and these gaps have to be filled in by imagination. While Marupiravi was written in a loose manner with much room for imagination, Aliyah was written with a clear historical perspective. “Since I have been an eye witness to their life, I was able to empathize with their lives and thus was able to structure the novel”, Sethu adds.

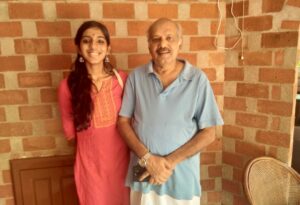

Sailaja with author Sethu Madhavan

The concept of diaspora has been critically studied in the novel. The main conflict that arises here is the dichotomy between the terms “fatherland” and “motherland”. The elders in the community hold on to migration due to their firm belief in the faith and to die in Jerusalem, their holy land. The youth however are much attached to their motherland Kerala, the land they grew up in and were attached to. They preferred the practical option of staying back rather than migrating to a land monotonously chanted about in the holy text.

Mr. Sethu also notes that it was due to the benevolence of Cochin Royal Family that diverse ethnic groups coexisted in this region. The Royal Crown subsidised Hebrew classes for the Jews and exempted Jews from writing examinations on Saturday (Sabbath). He also mentions his friend, Mr. Eliyahu who was known for innovations in agriculture and also known for developing the Israeli Model of Irrigation, who happens to be a resident of Chendamangalam too.

Mr. Sethu also recalled how emotionally heart wrenching it was for him to see his friends leave out of the blue, and how even the Jews were helpless themselves to be leaving the land that had sheltered and fostered them for centuries. He also mentioned an incident where he ran into a friend who had migrated to Israel after 50 years. To him, this novel is a statement how a land like Kerala had taken diverse communities and fostered them and how all of them lived in harmony, contrary to the present day situation where people are in constant struggle with each other in the name of religious and caste taboos. Aliyah is a singular work highlighting the agonies of a community who have been displaced the most in the course of world history.

Get exciting updates about our events and more