Whats New: Check EVENTS to sign up for art workshops, Janal Talks, Film Screenings & More!

Whats New: Check EVENTS to sign up for art workshops, Janal Talks, Film Screenings & More!  Whats New: Check EVENTS to sign up for art workshops, Janal Talks, Film Screenings & More!

Whats New: Check EVENTS to sign up for art workshops, Janal Talks, Film Screenings & More!

Being a first of its kind in India, the Travancore Lines, famously known as Nedumkotta , situated in present day Thrissur district, represents a remarkable chapter in the military history of Kerala. Nedumkotta, a chain of forts that stretched approximately 50 km, played the role of safeguarding the northern border of the princely state of Travancore. It showcased advanced architectural skills, utilising natural features like hills, lakes, and rivers, along with a complex network of forts, trenches, moats, and caves, strategically positioned to deter any enemy incursions. Built on high ground, these bastions were colossal and consisted of occasional ramparts, in addition to which small forts were built at regular intervals. The north side of the Fort which was 50 feet high and trenches, 20 feet deep, were filled with poisonous snakes, thorny bamboos, and recondite traps. Along the moat, there was another palisade constructed with brambles and bamboo. It was an enigmatic construction used to shelter soldiers and store military accouterments. It also consisted of underground caves for guerrilla warfare along with wells dug at frequent intervals for adequate water supply for the soldiers inside the Fort.

In 1926 CE, an extensive study conducted by the Archaeological Department unveiled the grandeur of Nedumkotta. Featuring a formidable wall, it served as a protective barrier, connecting the Arabian Sea to the Western Ghats traversing the plains of the Chalakkudy River and the Periyar River. Starting at Krishnakotta on the West coast above Kodungallur, Nedumkotta stretched up to the Anamalai Hills on the Western Ghats.

In the chaotic landscape of 18th-century South India, the genesis of Travancore Lines unfolded in response to an ominous threat posed by the mighty Mysore army, commanded by the formidable Haidar Ali. He was a figure of great ambition, with his eyes set on the conquest of the entire west coast of India. His vision extended beyond territorial gain; it aimed to secure strategic dominance over vital western ports and create a formidable buffer against his arch-nemesis, the Kingdom of the Carnatic, led by the Nizam of Hyderabad.

In the year 1758 CE, King Karthika Tirunal Rama Varma of Travancore, took decisive action to counter this looming peril. He entered into a pivotal treaty with the rulers of Cochin, to fortify their northern borders. This treaty aimed not only to protect Travancore in the event of an invasion by the Mysorean forces but also to serve as a shield for the territories of Cochin from potential aggression by the Zamorin.

Under the terms of this agreement, the Raja of Cochin not only agreed to share the construction costs but also permitted the construction of the Line itself as the fortification would wind its way through Cochin’s territory in numerous places. The construction of Nedumkotta, as it came to be known, was carried out under the guidance of General D’Lannoy, commander of the Travancore army, alongside Ayyappan Marthanadan Pillai, the minister of Travancore, and Komi Achan, the minister of Cochin.

In 1766, Haider Ali invaded the northern regions of Malabar, which included the Zamorin’s territories. The Rajah of Cochin hastily pledged allegiance to Haider Ali. To secure this allegiance, Haider Ali stipulated certain conditions which included a requirement of four lakh rupees and the provision of eight elephants. Subsequently, Haider Ali turned his attention to the King of Travancore, where he made a demand for fifteen lakh rupees and twenty elephants. He threatened immediate invasion of Travancore’s territories in the event of refusal. The Travancore Maharajah, confident in the support of the English East India Company, declined to comply. The Maharajah mentioned that he was already paying tribute to the Carnatic Sultanate and could not serve two suzerains simultaneously. However, he expressed a willingness to offer a substantial sum if Haider Ali would reinstate the Kolathiri Raja and the Zamorin in their respective territories.

Travancore’s significance in this political scenario became evident as it sheltered exiled chieftains from Malabar who used the kingdom as a refuge and a base for resistance against Mysorean rule. These rebels, supported by Travancore, posed a persistent challenge to Haidar Ali, who viewed their activities as a direct provocation. The Raja of Travancore, aware of the political value of these rebels in destabilising Mysore’s rule, provided them with assistance,

In 1774 Haider again invaded Malabar and devastated the country. The Zamorin and other Princes of Malabar fled and took refuge in Travancore where they were provided protection and as a precaution, the Travancore Rajah soon initiated the expansion of the northern defensive lines, extending them within the firing range of the cannons stationed at the Dutch Fort in Cranganore and into the territory of the Cranganore Rajah. Recognising that this extension of defensive fortifications might potentially upset the Mysore Chief, the Dutch insisted that they cease their work within Dutch territory. The ammunition stores were replenished with fresh supplies to ensure readiness in unforeseen circumstances.

In 1776, Haider Ali launched a campaign to conquer Travancore and sought passage through Dutch-controlled Cranganore, which protected Travancore’s western flank. When Dutch Governor Moens declined his request, Haider dispatched a 10,000-strong army led by Sirdar Khan through Dutch controlled Cochin territory, capturing Trichur by August 1776. Later on, Sirdar claimed the Chetwai territory on behalf of Hyder Ali and began fortifying Paponetty while capturing most of the Cranganore Rajah’s territory, but was halted at the Travancore Lines. These developments involving Hyder were promptly communicated to the British. The Company decided to curb the growing influence of Mysore in the south, particularly due to the strong connections between Mysore and the French. Therefore the Company undertook the capture of Mahe, a port on the Malabar Coast under French control which was of great strategic importance to Hyder and this move from the Company led to a protracted war in which Travancore’s sepoys fought alongside the English forces.

In 1777, Travancore experienced a profound and irreplaceable loss when General De Lannoy, following a brief illness, passed away at Udayagiri. His death was mourned deeply by all in Travancore, as he was not only instrumental in introducing European military discipline to the Travancore army but also oversaw the construction of most of the forts in the region during his tenure.

In 1782, Hyder Ali succumbed to cancer, and his son Tipu succeeded him. The conflict persisted for an additional two years, during which Travancore’s troops demonstrated exceptional bravery and determination while fighting alongside the English. On March 11, 1784, the war came to a close with the signing of the Treaty of Mangalore. The invaluable assistance provided by the Travancore Raja and his forces were remembered by the Company. Notably, the Rajah of Travancore was explicitly included in the treaty as a friend and ally of the Company, with Tipu Sultan pledging not to engage in hostilities against British friends or allies. To secure his country further from a possible invasion, Rama Varma strengthened the northern defence of his country. Even after the passing of Haidar Ali, the Raja of Travancore continued to support the Malabar chieftains against Mysore, despite repeated warnings from Tipu against aiding his adversaries. The Raja’s steadfast defiance outraged Tipu.

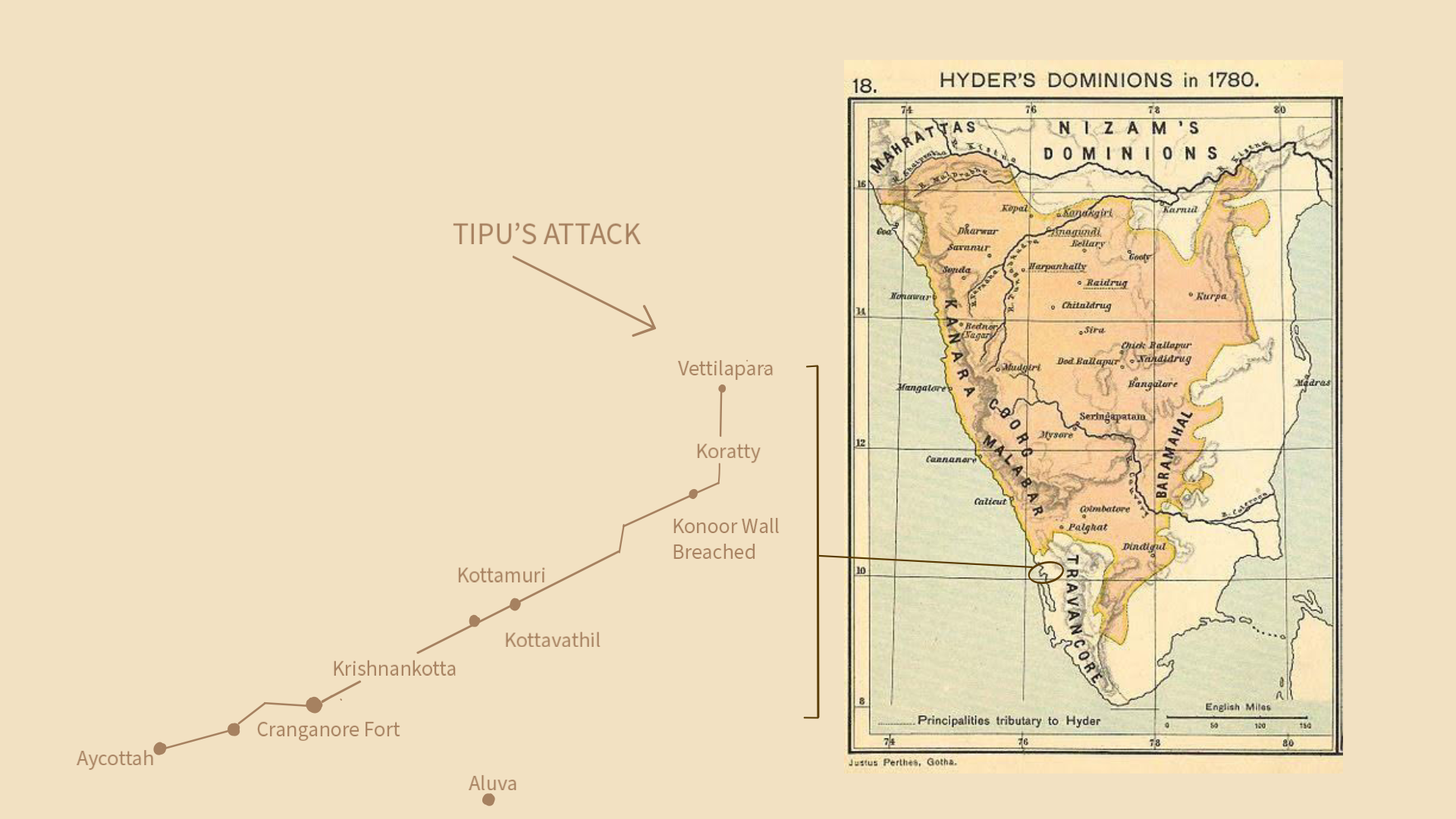

Later on, in 1788, the Raja had agreed to bear the expenses for maintaining two battalions of the Company’s native infantry, with a provision in the agreement stating that additional forces would be supplied at the Company’s expense if needed. Tipu Sultan, upon learning of this arrangement, grew furious and perceived it as a direct threat to his territory. He realised that Rama Varma’s defiance and confidence were emboldened by the protective barrier of the Travancore Lines. Therefore,Tipu demanded the demolition of that portion of the Lines which were erected into Cochin territory. He contended that the Lines cut him off from two-thirds of Cochin territory which lay to their south, but Rama Varma refused to comply with the demand citing that the Lines were constructed some 25 years ago and before the Raja of Cochin became a tributary of Mysore. Besides his refusal to demolish the Lines, the Raja of Travancore acquired the strategically vital Dutch forts at Crangannore and Ayakkotta in 1789, even as Tipu Sultan was still in negotiations with the Dutch to secure these forts. This further enraged Tipu and ultimately led to his attack on Travancore.

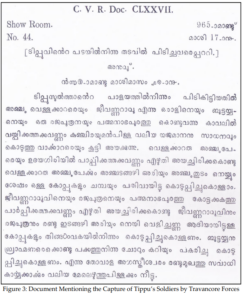

The attack by Mysore forces on the forts started on 18 December 1789, with 30,000 infantry, 5000 Cavalry, and 20 cannons. A contingent of Mysorean soldiers ventured deep into the jungles of Travancore. The Mysorean troops launched an assault on the eastern section of the Travancore Lines, managing to capture the ramparts as the Travancore soldiers began a tactical retreat but the features of the Fort were unknown to the Mysore troops. In a twist of fate, an unforeseen guerrilla attack by the Travancore forces, emerging from within the fortress, struck with deadly force. The Mysorean commanding officer met his demise. This sudden counterattack threw the Mysore army into a state of complete disarray, compelling them to retreat. Amidst the chaos, the moat constructed on the northern side of the Fort proved to be a formidable obstacle, inflicting heavy casualties upon the Mysore forces.

Following his previous failure, Tipu was determined to retaliate against Travancore, maintaining a large army comprising infantry, cavalry, and artillery near the northern frontier. The British East India Company was informed of Tipu’s position, and the Maharaja received assurances of British assistance. Travancore, in response, reinforced its northern frontier line, concentrated available troops, and initiated recruitment efforts. Arsenals were stocked with guns, stores, and ammunition.

In 1790, a contingent of 1,000 Travancore soldiers embarked on an expedition into Mysorean territory but suffered substantial casualties when they were forcefully pushed back by Mysorean forces. Subsequently, Tipu’s artillery began bombarding, yet it proved ineffective against the formidable fortifications for nearly a month until a breach, spanning three-quarters of a mile, was finally achieved.

The Travancore troops abandoned their positions, and Tipu Sultan advanced with around 6,000 soldiers. Tipu successfully occupied Cranganur. Subsequently, Travancorean forces abandoned forts such as Aycotta and Parur. A portion of Mysorean troops moved to Kuriapilly, which had also been abandoned by the Travancoreans. The entire defensive line fell into the hands of the Sultan, along with ammunition and war supplies but he could advance only as far as Aluva as the onset of a severe southwest monsoon caused great inconvenience to his army. The Aluva River overflowed its banks, impeding Tipu’s march. They lacked shelter and their ammunition and provisions were affected. While Tipu was encamped at Aluva, news of the commencement of hostilities and the assembly of a large East India Company force at Trichinopoly reached him. Faced with these challenges and the inundated terrain, Tipu Sultan was compelled to make a hasty retreat.

The incident at the Travancore Lines did not escape the attention of the British East India Company, which saw it as a violation of the Treaty of Mangalore. Using this as a pretext, the Company declared war on Mysore in 1790. This led to the formation of a coalition of regional powers against Tipu Sultan, with the British forging alliances with other states, ultimately resulting in the defeat of Mysore and the containment of Tipu’s expansionist ambitions. The Travancore forces joined the British army at Falghautcherry, Coimbatore, and Dindigul, fighting under British officers’ command against Mysore until the war’s conclusion and the signing of the Treaty of Seringapatam.

This peace settlement with Tipu Sultan brought great relief to the Travancore Maharajah. However, this hope was short-lived as the English Company demanded that the Maharajah bear the entire expenses of the war, which they claimed was fought to safeguard Travancore’s interests. This demand went against the 1778 agreement, in which the Company explicitly stated that if additional forces were required in the Travancore frontier beyond the two companies already stationed there, such forces would be funded by the Company. This exorbitant demand, violating a clearly expressed treaty and coming at a time when the state’s finances were in poor shape, deeply troubled the Maharajah. Nonetheless, he was advised by his minister to pay the amount to the Company.

Today, National Highway 66, one of India’s main national highways, intersects the area where Tipu Sultan’s troops destroyed the Fort. While Tipu’s invasion resulted in the Fort’s destruction, a few portions managed to survive into the 19th century. However, most of the Fort has been devastated over time due to relentless developmental projects and neglect from authorities. Fragments of a hill associated with Nedumkotta still exist in the village of Koratty in Thrissur district. This place holds significant historical importance for Nedumkotta, marked by a memorial tablet at the hill’s peak inscribed as ‘Konoor Kottavathil’ breached by Tipu Sultan in December 1788.

Nedumkotta, the guardian of Southern Kerala against Mysorean invasions, is crucial in the socio-political and military history of Kerala. It stood out with its distinctive architectural characteristics and its substantial scale. The strategic location of the fortification, its invincibility, resourcefulness and purpose remain as a benchmark in the military history of a turbulent era in Kerala. The great Nedumkotta was the only blockade that precluded Tipu Sultan from conquering the southwestern part of the Indian subcontinent showcasing its unparalleled significance.

1758 CE: Treaty signed between King Karthika Tirunal Rama Varma of Travancore and Cochin rulers to fortify their northern borders, marking the beginning of Nedumkotta.

1763 CE: Zamorin pays a visit to the Travancore Raja at Padmanabhapuram, leading to friendly relations among the rulers of Cochin, Travancore, and Calicut due to the threat posed by Mysore under Haider Ali.

1766 CE: Hyder Ali captures northern Malabar, including the Zamorin’s domains, prompting the Cochin Rajah to pledge loyalty. Hyder Ali demands four lakhs of rupees and eight elephants from Cochin, as well as fifteen lakhs of rupees and twenty elephants from Travancore. Travancore’s ruler declines, seeking aid from the British East India Company and fortifying his northern defenses.

1774 C.E: Hyder Ali invades Malabar again, devastating the region

1776 CE: Hyder Ali sets out to conquer Travancore. He demands a free passage through Dutch territories into Travancore but is denied and Sirdar Khan, under Hyder Ali’s orders, invades northern Cochin. Haider Ali’s army captures Trichur and part of Cranganore but is halted at the Travancore Lines.

1777 CE: General De Lannoy, instrumental in fortifying Nedumkotta, passes away.

1780 CE: The SecondAnglo Mysore War commences

1782 CE: Haider Ali dies, and Tipu Sultan succeeds him.

1784 CE: Peace treaty signed with Mysore, and Travancore’s assistance is acknowledged by the British.

1787 CE: Tippu Sultan reconnoiter roads leading into Travancore and invades Malabar. He demands the surrender of refugees who fled to Travancore and is refused by the Maharajah and therefore plans for the subjugation of Travancore.

1788 – 1789 CE: Tipu Sultan demands the removal of a section of the Travancore Lines, which Rama Varma rejects. Meanwhile, the Dutch sell the forts of Cranganore and Ayacotta to Travancore. In response to potential threats, Travancore’s Rajah seeks aid from the British Governor, allowing Company troops to be stationed in the region for defense. Subsequently, Tipu Sultan launches an assault on Travancore’s lines near Cranganore, breaching a vulnerable portion. However, reinforcements from the Raja of Travancore’s forces repel Tipu Sultan’s attack, forcing his retreat.

1790 CE: Tipu Sultan launches a second attack that breaches the fort’s walls, leading to its eventual capture. Subsequently, the English declare war against Tipu Sultan. His forces breach the lines near Ayacotta and enter Travancore, seizing Cranganore and Kurinpalli. As they march southward in Travancore, Tipu Sultan’s forces grapple with adversities, including monsoon rains and disease. Eventually, before departing Malabar, Tipu Sultan orders the complete destruction of the defensive lines.

1791 CE: Travancore forces participate in the broader conflict against Mysore alongside the British East India Company.

1792 CE: Treaty of Seringapatam is signed, recognizing Travancore as a friend and ally of the English.

1809 CE: British authorities intentionally destroy parts of Nedumkotta due to landslide risks.

19th Century: Remaining portions of Nedumkotta are used by British troops.

Present Day: Some place names in the northern borders of the Travancore-Cochin State still carry references to the fortification, but visible remnants of the fort are largely absent.

Veeraraghavapuram, Nagam Aiya (11 July 1906), Travancore State Manual, Trivandrum, p. 395

Kunju, A. P. Ibrahim. “RELATIONS BETWEEN TRAVANCORE AND MYSORE IN THE 18th CENTURY.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 23, 1960, pp. 56–61. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44137497.

Menon, P. Shungoony (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Bothyam and co.

SR, Bipin Kurup, and A. S. Vysakh. “Nedumkotta: An Archaeological Study of a Fate-changing Fortification of Kerala.”

Panikkar, K. M. : A History of Kerala (1960)

Get exciting updates about our events and more